As the biggest company in the world, Apple operates to different rules from other businesses. That was apparent against last week when Tim Cook, Apple’s chief executive, partly blamed weaker-than-expected iPhone sales on leaks about future products.

Cook said that there had been a “pause in purchases” due to “earlier and much more frequent reports about future iPhones”.

There is undoubtedly some truth in this – why buy a product when you know a better version will be available in a few months? However, this is an issue that Apple faces every year; indeed, it is something that it actively encourages with its glitzy ceremonies to launch new and upgraded products.

Wall Street appears to have shrugged off the news that Apple missed expectations, because shares in the company still rose 3% over the last week. It remains the most valuable company in the world, with a stock market value of more than $750bn (£579bn).

However, the quarterly results are a reminder that the company is far from infallible and that its extraordinary run of success since launching the iPhone in 2007 is nearer the end than the start.

Apple reported iPhone sales of 50.8m in the first three months of 2017, down by 1% year-on-year. Its revenues grew 5% to $52.9bn, which was just below analysts’ forecasts of $53.1bn.

The company’s financial performance is heavily reliant on the iPhone. While it generated more than $33bn of sales in the quarter, a category it defines as “other products”, which includes the iPod, Apple TV and the Apple Watch, generated just $2.9bn.

While the Apple Watch may be popular with those who use it, it has certainly not created a new platform of customers for the company to meaningfully develop – not yet, anyway.

Reports in the technology industry suggest that the next iPhone will be a significant step forward. According to rumours, it could include wireless charging, 3D facial recognition and a curved display. But even so, an upgrade to an existing product is unlikely to be a game-changer in the same way that the original iPhone was a decade ago, or the iPod and the iPad were.

It is also worth remembering that Apple saw sales of the iPhone decline in 2016; last October, the company revealed its first fall in annual sales and profits in 15 years.

It would be foolhardy to call this the peak for Apple, because you can never be sure what mystery products are lurking in its research and development buildings. However, it is clearly becoming more difficult for Apple, Samsung and others to expand the smartphone sector. The devices are now effectively a commodity, particularly in the western world. The market is for customers looking to upgrade every couple of years rather than those looking to buy their first handset.

But a slowdown in its biggest market makes the $250bn cash mountain that Apple is still sitting on even more intriguing.

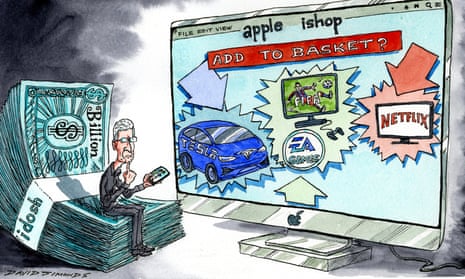

Analysts at Citigroup, the investment bank, have drawn up a list of seven companies that Apple could buy with the cash. Their candidates are Netflix, Walt Disney, Tesla, streaming service Hulu, and video game makers Activision Blizzard, Electronic Arts and Take Two Interactive.

Some of these deals, such as Disney or the videogame makers, would basically be bolt-ons that would allow Apple to share the success these businesses already enjoy.

Buying Tesla, however, could be transformative and help Apple down the path towards transferring its technology to driverless and electric vehicles. Rumours suggest that Apple may already be working on an electric vehicle anyway.

Even if Apple does not do a deal, it seems its next move will be about bringing its technology closer to our everyday lives, whether through a car or turning its headphones into health monitors, another rumoured plan.

As smartphone sales slow, we are closer than ever to finding out what Apple’s next move will be.

In the wrong at Pearson

Pearson chief executive John Fallon’s suggestion that he was somehow doing the decent thing was irritating. After collecting a £343,000 bonus for a year in which the educational publisher lost £2.6bn, Fallon told shareholders on Friday: “I don’t decide what CEOs get paid but I did decide once the payment was made that the right thing to do was buy shares in Pearson.” No, Mr Fallon, after a year like 2016, the right course was to waive the bonus and rub along on your £780,000 salary.

It is true that the last of the five profits warnings in the past four years arrived a few weeks after the end of Pearson’s financial year, but it was a humdinger of a warning. It signalled a cut in the dividend this year, thereby removing the sole source of solace for investors during Fallon’s ill-starred reign. The share price, even after the bounce that accompanied the unveiling of yet another restructuring plan, has halved in little more than two years.

Fallon is correct that the remuneration committee sets his pay. Thus Elizabeth Corley, chair of that committee, and Sidney Taurel, group chairman, must take direct blame for a fiasco that saw almost two-thirds of voting shareholders oppose the remuneration report. Almost a third also opposed Pearson’s forward-looking pay policy. That level of opposition is extremely rare at FTSE 100 companies.

Corley also received a 27% vote against her re-election. She is the former chief executive of giant investment manager Allianz Global Investors, so this was a case of shareholding fund managers voting against one of their own. She should take the hint and go. Pearson’s commitment to “continuing dialogue with our shareholders” on pay will look thin if the same individual is sent out to bat again.

“We’re the world’s learning company,” says the corporate blurb, but Pearson has shown zero understanding of the public anger over undeserved corporate pay. The lesson isn’t hard: when you’ve reported record losses, don’t give the boss a bonus.

Shale industry turns tables on Opec

Oil industry hopes that the price of Brent crude would stabilise at around $60 (£46) a barrel were dashed last week.

The price was supposed to rise from the average of $55 seen over recent months, following a squeeze on oil production orchestrated by Saudi Arabia and the 13-nation Opec cartel. An improving global economy was also expected to push the price higher as global demand outstripped supply. Indeed, BP and Shell reported bumper profits last week amid signs of an upturn for the big industry players.

But US shale operators have had other ideas. They turned on the taps once the price passed $50 and their derricks became profitable again. This led to the oil price falling below the $50 mark again last week.

For consumers, it spells a return to lower prices at the petrol pumps and some relief from rising inflation. For the industry and Opec, however, it confirms that shale provides an effective cap on prices however hard they work.