At last week’s Worldwide Developers Conference (WWDC), Apple made an unusually large number of hardware and software announcements. Today we’ll look at a potential connection between Apple’s silicon design strengths and its just-unveiled augmented reality and machine learning applications development tools.

When Apple introduced its 64-bit A7 processor in Sept. 2013, they caught the industry by surprise. According to an ex-Intel gent who’s now at a long-established Sand Hill Road venture firm, the competitive analysis group at the imperial x86 maker had no idea Apple was cooking a 64-bit chip.

As I recounted in a Sept. 2013 Monday Note titled “64 bits. It’s Nothing. You Don’t Need It. And We’ll Have It In 6 Months,” competitors and Intel stenographers initially dismissed the new chip. They were in for a shock: Not only did the company jump to the head of the race for powerful mobile chips, but Apple also used its combined control of hardware and software to build what Warren Buffett refers to as a wide “wide moat”:

In days of old, a castle was protected by the moat that circled it. The wider the moat, the more easily a castle could be defended, as a wide moat made it very difficult for enemies to approach.

The industry came to accept the idea Apple has one of the best, if not the best, silicon design team; the company just hired Esin Terzioglu, who oversaw the engineering organization of Qualcomm’s core communications chips business. By moving its smartphones and tablets—hardware and software together—into the 64-bit world, Apple built a moat that’s as dominant as Google’s superior Search, as unassailable as the aging Wintel dominion once was.

I think we might see another moat being built, this time in the fields of augmented reality (AR), machine vision (MV), and, more generally, machine learning (ML).

At last week’s WWDC, Apple introduced ARKit (video here), a programming framework that lets developers build augmented reality into their applications. The demos (a minute into the video) are enticing: A child’s bedroom is turned into a “virtual storybook”; an Ikea app lets users place virtual furniture in their physical living room.

As many observers have pointed out, Apple just created the largest installed base of AR-capable devices. There may be more Android devices than iPhones and iPads, but the Android software isn’t coupled to hardware. The wall protecting the massive Android castle is fractured. Naturally, Apple was only too happy to compare the 7% of Android smartphones running the latest OS release to the 86% of iPhones running iOS 10.

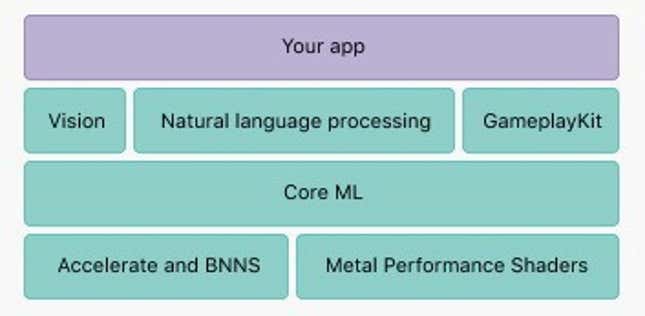

Apple also introduced CoreML, an application framework that integrates “trained models” into third-party apps. Unlike with ARKit, there were no fun CoreML demos; CoreML implementations will be both “everywhere” and less explicit than AR. Architecturally, CoreML is a foundation for sophisticated machine vision and natural language processing apps:

As far as we know, all of this runs on the Ax processors in recent iPhones and iPads. But a recent, unsubstantiated Bloomberg rumor has aroused interest: “Apple Is Working on a Dedicated Chip to Power AI on Devices.”

Auxiliary chips that run to the side of the main processor, dedicated to a specific set of operations, have (almost) always existed. The practice started with FPUs (Floating Point Processors). High-precision Floating Point operations, mostly for scientific and technical applications, demanded too much from the main CPU (central processing unit), slowing everything down. Such operations were offloaded to specialized, auxiliary FPUs.

Later, we saw the rise of GPUs, graphic processing units, dedicated to demanding graphics operations, simulations, and games. Because of the prevalence of graphics-intensive apps and the demand for reactive, no-lag interactions, GPUs are now everywhere, in PCs, tablets, and smartphones. Companies such as Nvidia made their name and fortune building a range of high-performance GPUs.

These are impressive machines. Stripped of the logic (transistors) needed for the complex logic operations of general purpose CPUs, GPU hardware resources are dedicated to a narrow set of tasks performed at the highest possible speed. Think of a track car with none of the amenities of a road vehicle, running much faster but unsuited for everyday road and city use.

Such was the performance of GPUs that some financial institutions experimented with machines that harnessed hundreds of GPUs in order to execute complex predictive models in near real-time, giving them a putative trading advantage.

A similar thought arose with the need to run complicated convolutional neural networks and related ML/AI computations. This led Google to design its TPU (tensor processing unit) to better run its TensorFlow algorithms.

Back to the dedicated AI chip rumor: It’s an attractive story that comes from a source (Bloomberg) that has a record of eerily accurate predictions mixed with a few click-baiting bloopers.

Let’s indulge in a bit of speculation.

Tentatively dubbed Apple Neural Engine (ANE), this hypothetical chip fits well with Apple’s tradition of designing hardware for its software, following Alan Kay’s edict: “People who are really serious about software should make their own hardware.”

Couple Apple’s AR and ML announcements with the putative ANE chip and we have an integrated whole that sounds very much like the Apple culture and silicon muscle we’ve already witnessed, a package that would further strengthen the company’s moat, its structural competitive advantage.

It’s an attractive train of thought, although possibly a dangerous one, in the vein of “It’ll work because it’d be great if it did.” That perfunctory precaution taken, I’d give it more than an even chance of becoming reality in some form. Or your Monday Note subscription money back.