What Apple Thought the iPhone Might Look Like in 1995

More than a decade before the smartphone was unveiled, the tech giant made a mock-up design for a videophone-PDA that could exchange data.

A decade ago, for the most part, phones were phones. Computers were computers. Cameras were cameras. Portable music players were portable music players. The idea that the future of the computer would be a phone, or vice versa, wasn’t merely absurd. It just wasn’t how people thought about consumer technology. At all.

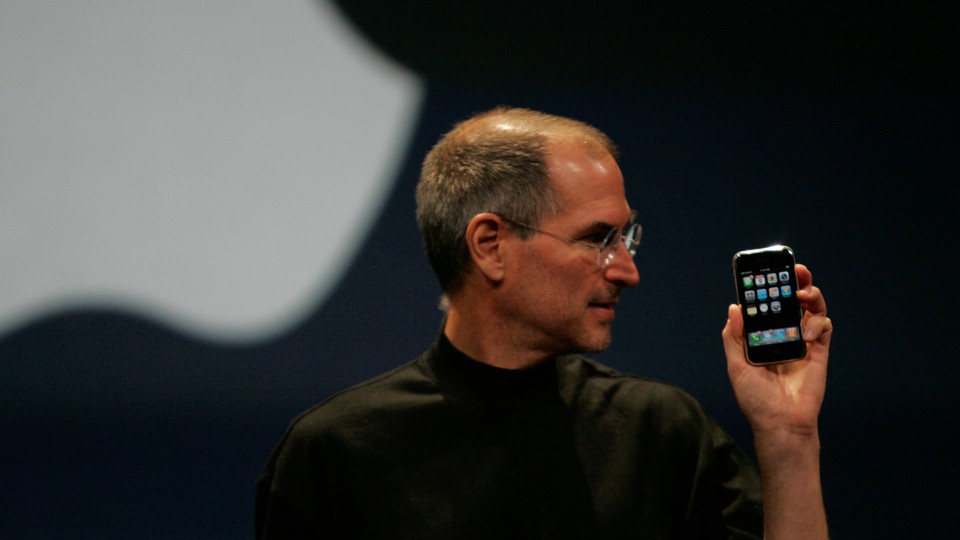

So when the first iPhone was unveiled in 2007, plenty of people assumed it wouldn’t change the world. (“Touch-screen buttons? BAD idea. This thing will never work,” as one naysayer put it at the time.)

To those who had been watching Apple since the 1980s, however, shrinking computers and videophones seemed to be always just tantalizingly out of reach, emblems of a future that would, fingers crossed, eventually arrive.

But when? By 1995, even though Apple’s laptops had dipped to a svelte six pounds, and the transformative power of the internet was becoming apparent, the next great iteration of the web was barely imaginable. Today’s mobile web, the one that would be ushered in by smartphones, was still out of reach. But there were hints of what was to come.

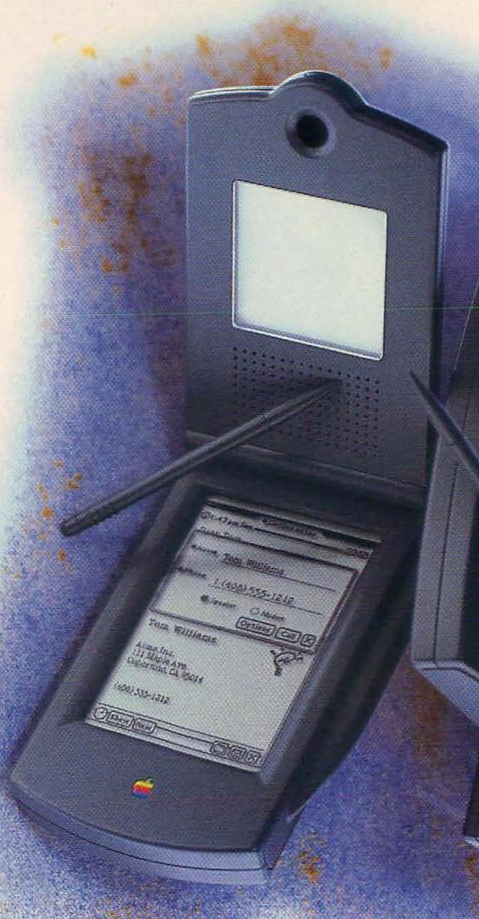

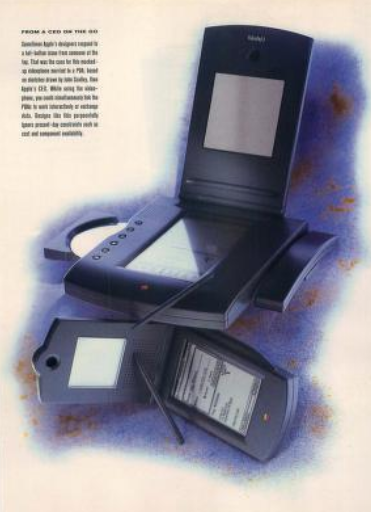

Apple has always been fond of dreaming up hardware and software from a not-too-distant future, and there are glimmers of the iPhone in Apple’s history since long before the rumors about the device were taken seriously in the early 2000s. More than a decade before the smartphone was unveiled, Apple shared with the computing magazine Macworld a semi-outlandish design for a videophone-PDA that could exchange data. (Smartphones eventually made the PDA, or personal digital assistant, obsolete.)

The prototype for the device, published in the May 1995 issue of the magazine, is something of a missing link between the Newton and the iPhone—though still more parts the former than the latter. The Newton was Apple’s lackluster PDA, first released in 1987, 20 years pre-iPhone. The Newton may have been ahead of its time in some ways; but it also failed because it was pricey and didn’t work particularly well. (In 1993, one pithy New York Times writer memorialized his attempts to write on the device this way: “This is being writings a worth it takes a while before the handed tiny red floor is footprint. Signed, Bite (poof!) Beers (poof!) been (poof!) I sits.”)

The Macworld prototype combined a PDA and a videophone, complete with handset, and visualized a future in which the devices would be able to exchange data. Naturally, because this was 1995, the concept also included a CD drive and a stylus.

The design was made public as part of a collection of several made-up Apple products, all published in that same 1995 issue of Macworld. The spread is charming in retrospect, but also revealing for how it signals a shift in the way Apple was changing the way people thought about the intersection of design and technology. Flipping through the old issue of Macworld this week made me think of a conversation I had last year with Robert Brunner, the industrial designer who worked for many years at Apple and now runs his own design studio.

“When I started out in my career, design was seen as a necessary evil, especially in relation to technology,” Brunner told me at the time. “It moved into this phase where all of the sudden people saw design as a corporate identity thing, like ‘all of our products need to look alike.’ In the early 1990s, it moved into innovation for innovation’s sake. And then there started being this shift, driven somewhat by Apple, where people began to understand that design was what made them want your technology to be part of their lives.”

Design isn’t just the aesthetic quality that makes a device beautiful or identifiable by brand, in other words. It is a core part of how the technology works. Brunner attributes that cultural change largely to Jony Ive, Apple’s chief design officer, and his team’s work over the last 10 years. “Jony and his team have changed the way people see design,” Brunner told me.

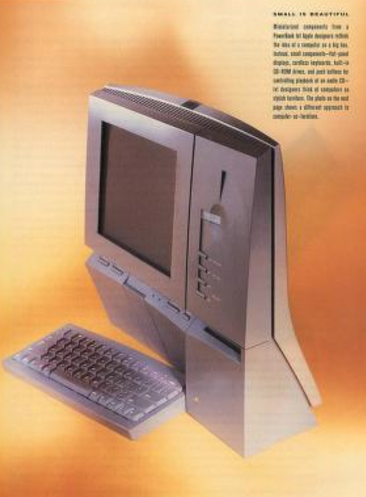

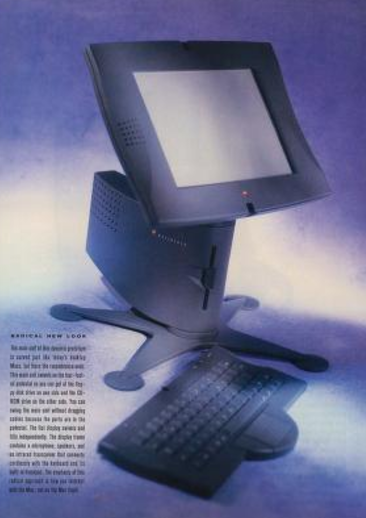

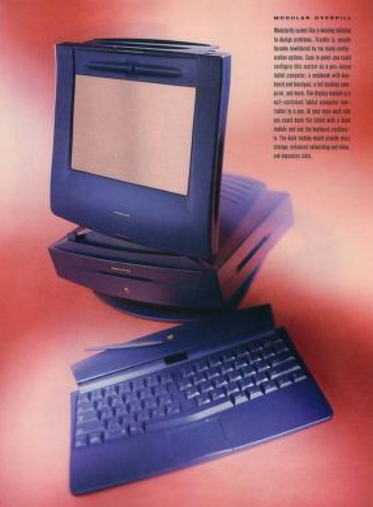

You can see the stirrings for this change in attitude across the pages of the 1995 Macworld spread. Computers are compared to “stylish furniture,” and to “strong personal statement piece[s]” of art, namely Richard Sapper’s minimalist, counterweighted Tizio lamp.

In the caption for one imagined computer of the future—a curved and dynamic prototype that was designed to swivel on a four-footed pedestal “so you can get at the floppy disk drive on one side and the CD-ROM drive on the other side”—Macworld described the change that was taking place in the design world explicitly, because at the time it still needed to be said: “The emphasis of this radical approach is how you interact with the Mac, not on the Mac itself.”

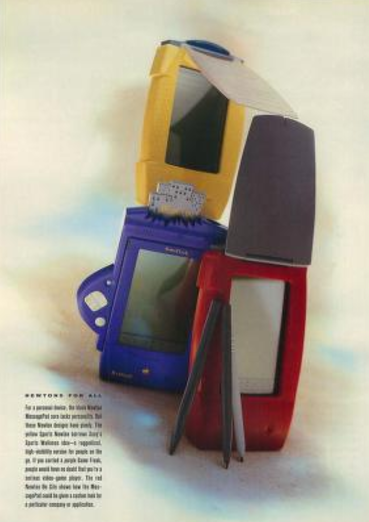

A new concept for the Newton made an appearance in Macworld, with Apple adding splashes of color that would eventually reach the market with the iPhone’s colorful, plastic 5c models. “For a personal device, the black Newton MessagePad sure lacks personality,” Macworld wrote back in 1995. “But these Newton designs have plenty. The yellow Sports Newton borrows Sony’s Sports Walkman idea—a ruggedized high-visibility version for people on the go. If you carried a purple Game Freak, people would have no doubt that you’re a serious video-game player. … The MessagePad could be given a custom look for a particular company or application.”

But at the time, most of these computer-of-the-future designs were seen as impractical—too confusing, too far outside the realm of what was technologically possible (or even desirable) for consumers at the time.

Looking back now, two decades since the Macworld feature and one decade since the iPhone reached the market, it’s clear that Apple’s smartphone has forever altered industry standards for electronics design. Losing the keyboard and prioritizing software over hardware was crucial to the iPhone’s success—as was playing up the phone in iPhone to distance the device from the failed Newton that preceded it. “I don’t want people to think of this as a computer,” Steve Jobs, the former Apple CEO, told John Markoff, the veteran technology writer for The New York Times, when Jobs introduced the iPhone in January 2007. “I think of it as reinventing the phone.”

Where Apple’s past failures had always hummed with untapped potential, as one newspaper columnist described the Newton in 1993, the iPhone elegantly and boldly realized it. The device would go on to dramatically reconfigure social norms and behaviors. It changed how people socialize, how people work, how people shop, how people seek information, and how designers think about technology. Gorgeous design is now mainstream. “With the escalation of average design—average is now pretty good, right? So you have to even look harder for what’s really good,” Brunner told me.

“I think for us we constantly have to put more and more pressure on ourselves to be original and meaningful and not just derivative,” he added. “But there’s something unique about American design culture—and, in particular, Silicon Valley design culture—that really drives that originality. I think there’s something in the water here that drives people to always push to do something different, beyond the status quo.”

Even in 1995, Apple’s futuristic concepts offered a glimmer of what might come to pass, Macworld wrote at the time. “Although these prototypes won’t become real products, you can expect many elements to show up in real Apple products of the future,” the magazine said.

Macworld was right. But as we now know, the real products of the future were far better than even Apple’s wildest dreams just 22 years ago.