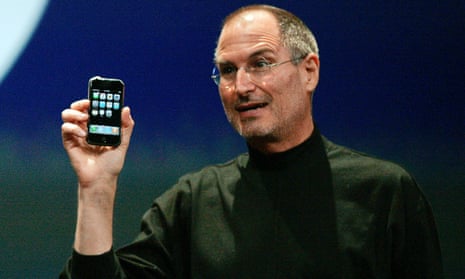

On Tuesday 9 January 2007, in the Moscone Center in San Francisco, the late Steve Jobs, dressed in his standard black turtleneck and jeans, announced that Apple had built a mobile phone. “The phone is rectangular,” reported CNN “and the entire front surface is a touchscreen. All of its functions are activated by touch, but when you bring your iPhone to your face, a proximity sensor will turn off the touchscreen so you don’t accidentally face-dial. The phone, which runs the Mac OS X, will be able to download and play both music and movies. It will come in two models – a $499 version with 4 gigabytes of memory and a $599 one with 8 gigabytes.”

Apple fans were predictably ecstatic – as they always were when His Steveness addressed them – but the rest of the world yawned. After all, the mobile phone business was a boring, mature global industry, dominated by Nokia. Apple knew nothing about the business, and Jobs had been able to negotiate a deal with only one mobile network company – Cingular, a branch of AT&T. Sure, the new gizmo had a web browser that worked – which Jobs said was “a real revolution” – and it could do email. But hadn’t he also said that “the killer app is making calls”? And the iPhone came with a battery that you couldn’t change! How dumb was that? Accordingly, Nokia executives slept easily in their beds – though their counterparts at RIM, which made BlackBerrys and had an unbreakable lock on mobile email, stirred uneasily in theirs, having noticed an $11 drop in their share price on the day.

Six months later, on 29 June, the first iPhones went on sale and the rest is history. Ten years on, Apple has sold 1.2 billion of them, in the process pulling in $738bn in revenue, and every year earning between 70% and 90% of all profits made by all smartphone manufacturers.

The iPhone made Apple the world’s most valuable company (with a market capitalisation of $771.44bn when I last checked) but, in a way, that’s the least interesting thing about it. What’s more significant is that it sparked off the smartphone revolution that changed the way people accessed the internet. Steve Jobs’s seminal insight was that a mobile phone could be a powerful, networked handheld device which could also be used to make voice calls. Turning that insight into a marketable reality was a remarkable achievement – commemorated last week by the Computer History Museum in a fascinating two-hour series of recorded conversations with the engineers who built the phone.

The result of this revolution is a world in which most people carry their internet connection around in their bags and pockets. It’s a world of ubiquitous connectivity in which people are never offline and are increasingly addicted to their devices. It’s got to the point where someone has coined a new term – smombies (zombies on smartphones) – to describe pedestrians who walk into obstacles because they are looking at screens rather than at where they’re going.

The smartphone is the most vivid example available of how technology can be – simultaneously – both good and bad, enabling and disabling, inspiring and disillusioning. The technical capabilities of modern phones are formidable and the ingenuity of the apps that harness those capabilities are often mindblowing. But at the same time, smartphones are also surveillance devices made in hell – pocketable slot-machines using GPS chips to track one’s every move, click, swipe and shake. And some of the apps that run on them are tailor-made vehicles for stalking, bullying, harassment and theft – to the point where parents who give smartphones to young children ought to be prosecuted for neglect.

The other consequence of a world in which most people connect to the internet via a smartphone is a vast increase in corporate power. This is because the smartphone – unlike a PC – is a tethered, closed device. Nothing gets on to an iPhone that Apple hasn’t explicitly approved; and although Android phones are less tightly controlled, Google is increasingly trying to enforce the same kind of order in that software ecosystem.

So while you may think that “your” iPhone is yours, in fact an invisible thread links it back to the mothership in Cupertino. And of course, much mobile connectivity comes not just via wifi, but courtesy of mobile phone networks, who are some of the biggest control freaks in corporate history. So even as we put on record our gratitude to Steve Jobs, we should also acknowledge that he has a lot to answer for. And that we should be careful what we wish for.