UPDATE

Alphabet (Google's parent company) announced that its Internet-connected balloon project, Project Loon is "graduating" from the experimental X program and spinning off into its own independent business (still under Alphabet).

The new company, which is changing its name from Project Loon to Loon, will continue working with mobile network operators to extend connectivity to rural and remote areas without Internet access.

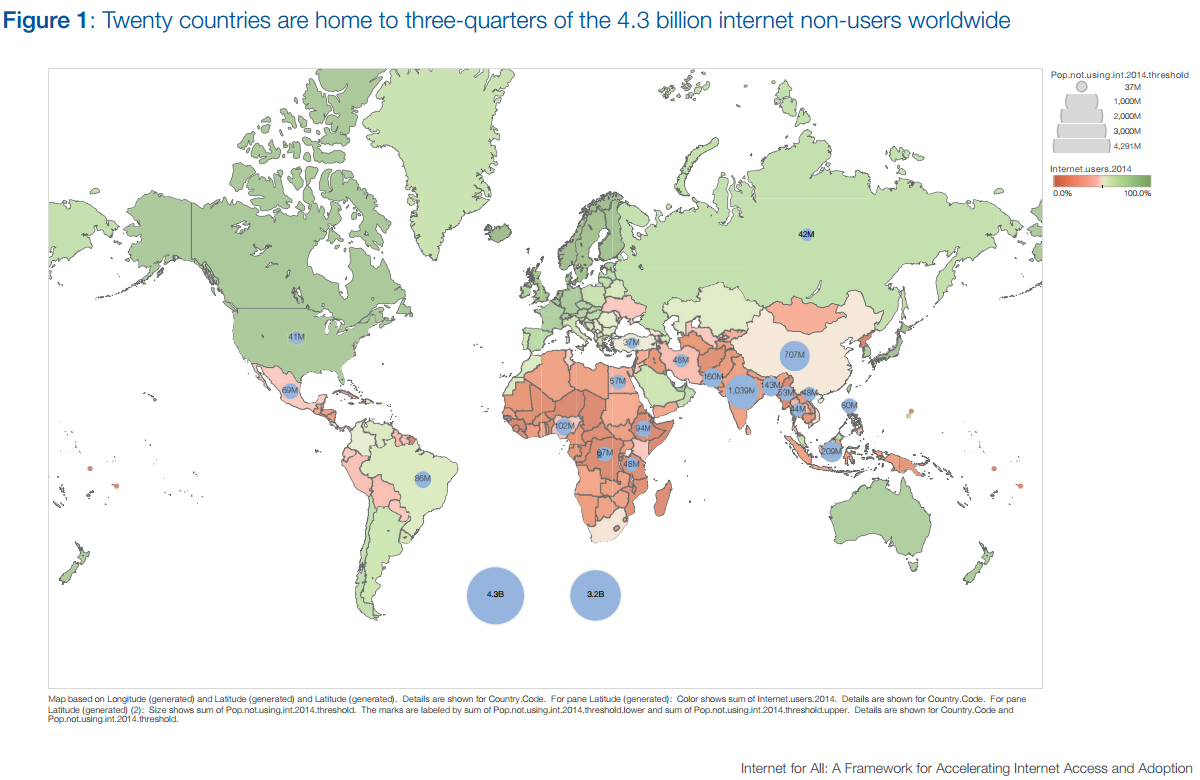

Our world seems more connected than ever. Google recently boasted that its Android mobile platform has over 2 billion users. A month later, Facebook said it had the same number of monthly active users. And yet, over 4 billion people around the world still don’t have access to the internet. Africa and South Asia are particularly affected: One of the lowest rates in the world is in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where merely 3.8% of the population has access.

But now Google, Facebook, SpaceX, and a handful of other startups are developing ways to get the rest of the world online. These companies’ motivations aren’t purely altruistic. These costly projects serve a dual purpose: as generators of good PR, as well as a gateway to billions of potential new internet-connected customers, who (they hope) will ultimately use their services.

This kind of connectivity could have a huge impact on the lives of those who live in rural areas, and other places where it doesn’t always make sense financially for cellular providers to put up a big, expensive cell tower that services a small number of people who may not be able to afford it.

Broadband internet isn’t just about getting more people into Snapchat; it has the potential to change people’s access to jobs, education, and information. “Historically, those communities have not been seen as the highest return of investment, where you’re looking at 50 homes within a wide span of land,” explained Dr. Nicol Turner-Lee, a fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Center for Technology Innovation. Governments do, occasionally, step in to invest in digital infrastructure where private companies fail to do so, but that’s more likely to occur in wealthy, developed countries, not emerging ones.

The process by which something gets to you via the internet involves a network of cables, data centers, and cell towers. The final step in, say, streaming an episode of Game of Thrones, involves your internet service provider (companies like AT&T, Verizon, and Comcast) sending that video over fiber-optic cables that eventually lead to a cell tower or to your house’s router.

It’s that last mile of internet connectivity — the part where the video travels from your ISP to you — that’s costly for areas that aren’t densely populated. But tech companies have some novel ways of solving this problem.

Elon Musk, CEO of Tesla and SpaceX, wants to blanket the Earth’s atmosphere with thousands of orbiting satellites (around 4,425, according to the original proposal), forming a global communications network that would deliver data to devices on the ground — but the first of SpaceX’s satellites aren’t slated to launch until 2019. Musk’s biggest competitor, the Virginia-based satellite company OneWeb, which aims to create a similar network that covers the entire globe with LTE connectivity, is hoping to launch in 2019, too.

Facebook also worked on a satellite designed to bring connectivity to parts of sub-Saharan Africa. In September 2016, it went aboard SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket. Unfortunately, that rocket blew up, destroying the satellite with it.

The company had another plan up its sleeve: a solar-powered, autonomous, internet-delivering drone called Aquila, with a huge wingspan (larger than a Boeing 737’s). The plan is to deploy a fleet of high-altitude drones that would communicate with each other via laser and fly for months at a time. Aquila is designed to beam wireless signal to people within a 60-mile diameter. The project still has a long way to go to hit that 90-day goal. In June, the drone completed a one hour, 46-minute flight.

One high-altitude solution that’s much closer to its goal is Project Loon, which is a part of X, Alphabet’s “moonshot factory” (formerly known as “Google X”). Like Aquila, Loon is an airborne internet network — except, instead of drones, it uses balloons filled with helium that float in the stratosphere. Loon’s flight record is 190 days and, while the project is still in a testing phase, its balloons have already delivered internet connectivity to tens of thousands of people in Peru, which was devastated by floods earlier this year. In February, Loon announced it had developed machine-learning navigation algorithms that allow it to send a much smaller fleet of balloons (dozens, instead of hundreds) to specific locations, making the project much cheaper than originally planned.

But the project isn’t without its setbacks. Loon has changed leadership twice within the past year. A key Loon patent involving balloon navigation was also canceled by the US Patent and Trademark Office, after a company called Space Data filed a lawsuit claiming it had come up with the idea first.

In any case, Alphabet has invested a significant amount of resources in Loon, with two launch locations (one in Ceiba, Puerto Rico, and the other in Winnemucca, Nevada) equipped with “autolaunchers” that can send up to 20 balloons a day into the stratosphere, balloon recovery missions all over the world, and labs back at X headquarters in Mountain View, California. One of Loon’s labs hosts the world’s largest flatbed scanner, named “Billie Jean” for the way its panels light up, which helps engineers and scientists examine every stress and stretch on the balloon’s plastic.

But lack of physical infrastructure isn’t the only thing preventing the widespread expansion of internet access. Device affordability, literacy, and creating websites available in local languages are also key to getting the rest of the world online. Furthermore, balloons, drones, and thousands of satellites may not bridge the digital divide in the areas that need it most — areas that have more pressing problems than lack of internet. “The real challenge [for these companies] will be getting to those areas that have … no running water, no electricity, no functioning schools,” said Turner-Lee.

And while these projects all sound promising, whether or not they will work in practice, outside of their tests on a large scale, remains to be seen. Silicon Valley-backed internet access projects have been met with controversy in the past, as with Facebook’s Free Basics program in India. Government authorization and cell provider cooperation are crucial to the progress of these developments. How will local governments and telecom companies treat experimental, airborne Google, Facebook, or SpaceX hardware floating overhead? Until Loon, Aquila, and Musk’s space internet take off widely, it’s hard to tell just how much they're going to change people's lives around the world.