Apple makes a lot of money off all those expensive iPhones we’re addicted to. So much that it has $252 billion to stash in countries besides the one where it is based—ours.

Apple has been doing this for years, but according to new documents released on Monday as part of the massive cache of secret corporate records called the Paradise Papers analyzed by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and its partner media organizations, the California-based tech giant has taken great lengths to continue its practice of tax dodging, including moving its cash to the island of Jersey, despite attempts by regulators to rein the company in.

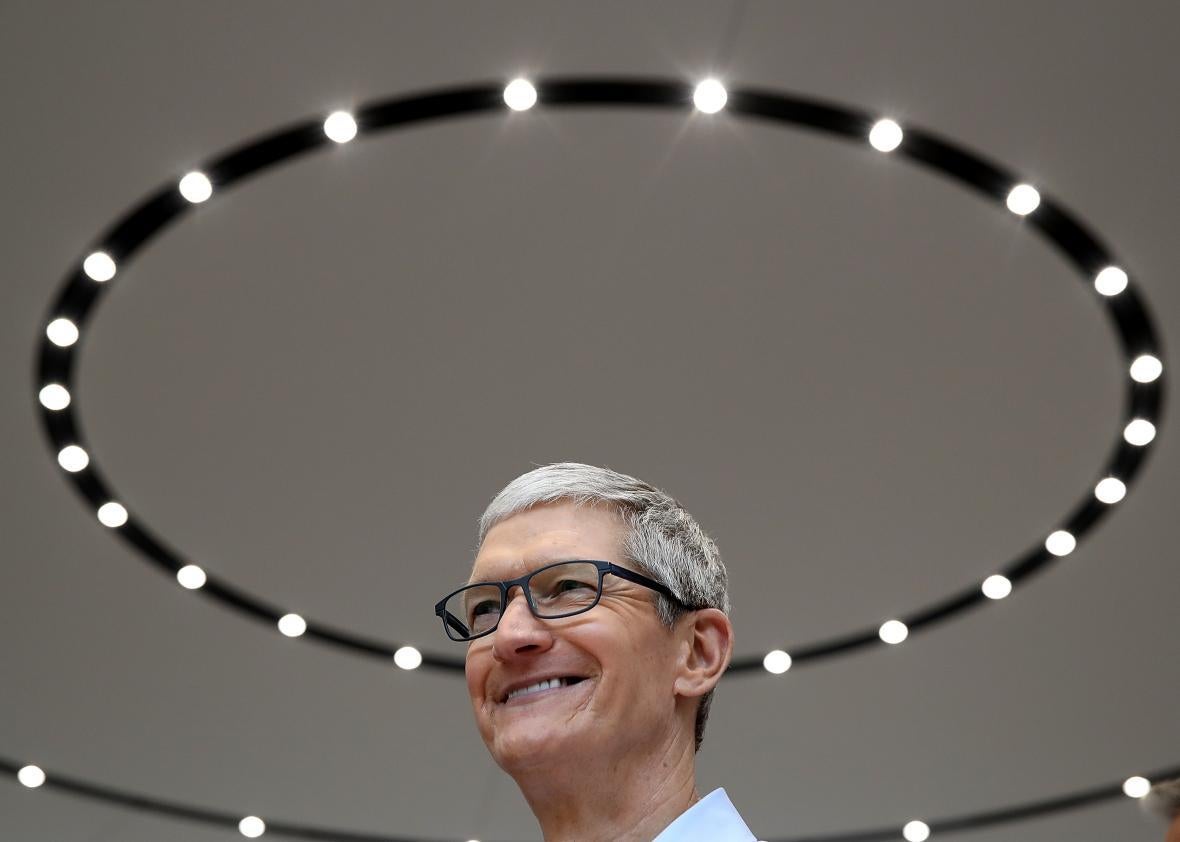

“We pay all the taxes we owe, every single dollar,” Apple CEO Tim Cook told U.S. senators in 2013, at a hearing of the Senate Permanent Committee on Investigations concerning how his company had avoided tens of billions of dollars in taxes by moving its profits to subsidiaries it owned in Ireland. “We do not depend on tax gimmicks. … We do not stash money on some Caribbean island.”

That statement is still technically true, since the place where Apple is currently storing most of its cash is on Jersey, an island in the English Channel about 19 miles off the coast of France. About five months after that hearing, Ireland started to scrutinize Irish firms, including Apple’s European arm, that were exploiting the country’s lax tax rules. That led Apple to start hunting for friendlier shores to store its money, according to the newly released documents. By the beginning of 2015, Apple had successfully restructured by moving two of its Irish subsidiaries, or what then-Sen. Carl Levin, a Democrat from Michigan and chairman of the aforementioned Senate panel, called “ghost companies,” just before the implementation of new, stricter Irish tax laws.

These companies weren’t really paying taxes, since they didn’t have a residency anywhere in the world that required them to do so. At the time, Irish law only considered a company to be a tax resident if it was managed in Ireland, but Apple is managed in Cupertino, California. And here in the U.S., our laws consider where a company is incorporated. “Apple has arranged matters so it can claim that these ghost companies, for tax purposes, exist nowhere,” said Levin at the 2013 hearing.

Apple’s relocation of these companies to Jersey was completed with help from Appleby, a law firm based in Bermuda that specializes in offshore tax avoidance—Appleby is also the firm from which the cache of secret documents that detail Apple’s tax moves originate. Apple had turned to its advisers at Baker McKenzie, a top U.S. law firm, for help. And Baker McKenzie then looked to Appleby for additional advice, sending a questionnaire to Appleby offices in the British Virgin Islands, Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, Guernsey, the Isle of Man, and Jersey.

That questionnaire asked the firms to “Confirm that an Irish company can conduct management activities (such as board meetings, signing of important contracts) without being subject to taxation in your jurisdiction.” It also wanted to know if Apple would have to relocate again. “Are there any developments suggesting that the law may change in an unfavourable way in the foreseeable future?” according to the New York Times, one of the media organizations that reviewed the documents.

The new information about Apple’s international tax dance comes just days after Republican lawmakers unveiled a new U.S. tax proposal that would reduce the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 20 percent.

“With this plan, we are making pro-growth reforms, so that yes, America can compete with the rest of the world,” said House Speaker Paul Ryan. Yet drawing from Monday’s disclosures, it appears some American companies, like Apple, are probably already paying taxes far shy of the 35 percent corporate rate, and in fact, are doing so thanks to tax havens outside of the United States. If the U.S. wants to be more competitive with those countries, well, it may have to stop taxing corporate profits all together.