When Chad Pierce and his family bought a new house this year, they made sure of one thing: that getting Internet service wouldn't be a problem.

"The first thing we did was go on [Charter] Spectrum's website and punch the address in," Pierce told Ars, recalling the day this past summer when he and his family saw the house in Newaygo, Michigan, that they'd ultimately buy.

The Charter website indicated that Internet service was available at the address. But Pierce wanted to make extra sure. "I had read articles saying the [Internet providers'] websites aren't always accurate," he noted. So he called Charter's customer service line and was told the same thing—that Internet was available.

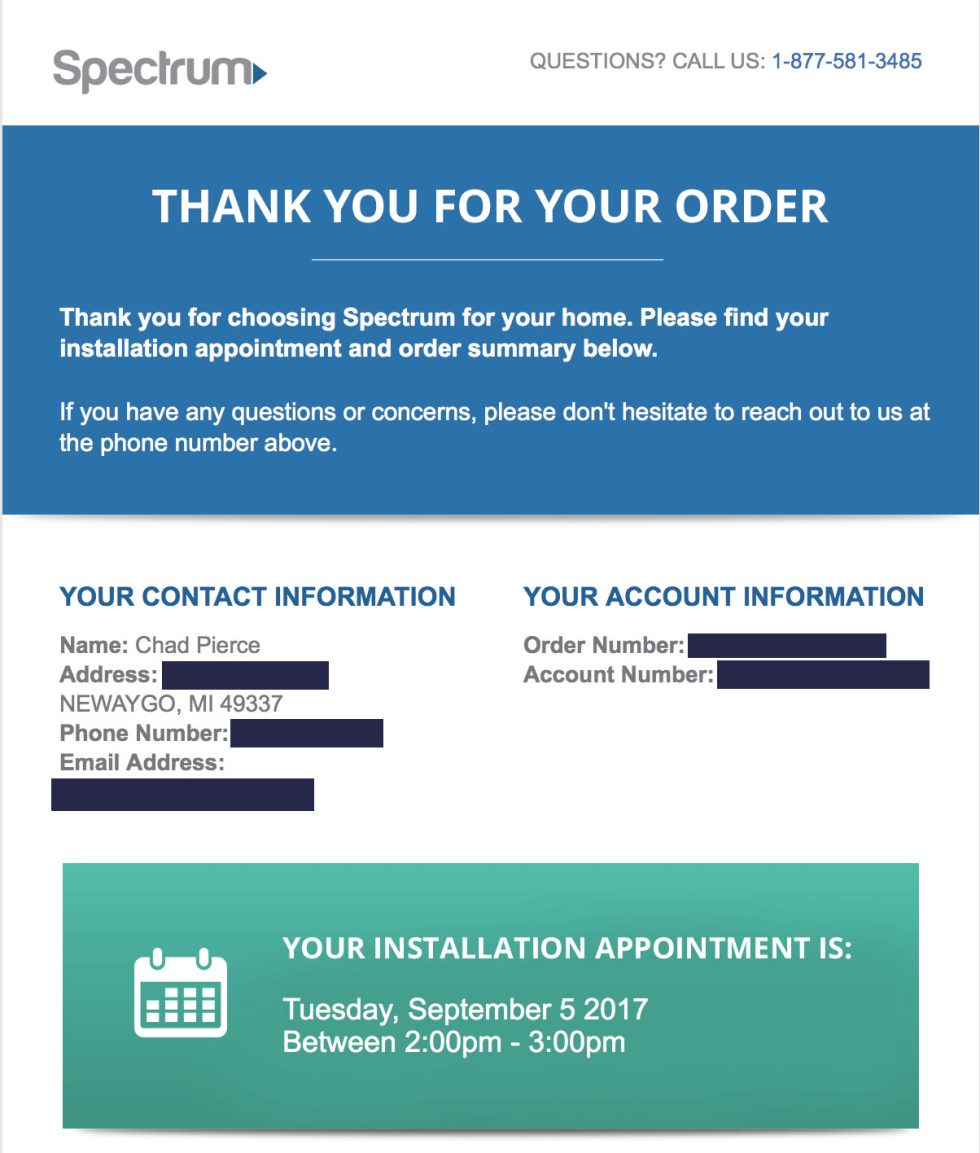

With that assurance, Pierce and his wife made an offer on the house and closed in late August. Pierce then called Charter again to set up Internet service, and there was still no sign of any problem. Pierce set up the appointment over the phone and got an email confirmation for his installation appointment scheduled for Tuesday, September 5, between 2 and 3pm:

The email also provided Pierce with an order number, an account number, and a detailed breakdown of the initial and monthly charges. But when September 5 arrived, he was in for a big shock.

"I got a call that Tuesday 45 minutes before the appointment from a dispatcher, saying apparently the house is too far from the road," Pierce said.

Internet service wasn't readily available—and Charter wouldn't extend its network to the house unless the Pierce family paid $16,000 to cover most of the company's construction costs. The house is about 550 feet from the road, Pierce said.

"Needless to say, we were pretty devastated," Pierce said.

No explanation for false information

Pierce has Internet service now from a local municipal broadband provider (more on that later). But his ordeal illustrates a problem we've written about multiple times: an Internet provider (such as Comcast) tells a new homeowner that service is available, only to later demand payment of thousands of dollars in construction fees in addition to the normal monthly service charges. In one previous case, Charter told a man who was building a house in Wisconsin that it could offer service to the property, but later said he'd have to pay $117,000.

When contacted by Ars about Pierce's situation, a Charter spokesperson confirmed that Pierce would have to pay for construction in order to get cable Internet service. But Charter offered no explanation for why the company falsely told the Pierces that service was available.

"We're looking into why the customer's address would have shown as serviceable, enabling him to schedule an appointment," a Charter spokesperson told us in early November. "It's definitely not currently serviceable: his home is about 2,000 feet from our nearest network location, and the total cost of building out to his home is more than $18,000 in labor, materials, permitting, etc. We've been on site twice and have verified there's no shorter or lower-cost approach."

We've followed up with Charter a few times since receiving that explanation but still have no answer for why the company set up an installation appointment at a house that it could not service. Charter is the second largest home Internet provider in the US, after Comcast.

The mess continues

Dealing with Charter was frustrating in other ways. After being told that he'd have to pay $16,000 for construction, Pierce asked Charter for a written estimate. Charter then provided a written estimate of about $2,300—but the name and address listed on the estimate was in a different city.

The estimate for the other address "was sent to Mr. Pierce in error," Charter told Ars. The $16,000 quote was the accurate one, Charter said.

Pierce offered to install conduit himself in order to lower the cost of construction, but that wasn't an option. "We don't have customers install conduit or really any network elements," Charter told Ars.

Pierce also contacted Charter's business Internet division, but they "could not help me because Comcast had business rights to my residence," he said. Pierce then contacted Comcast's business Internet division but was told that his house was un-serviceable, he said.

Pierce also has landline phone service from a small company, but that company could not offer DSL Internet at his house, he said.

Municipal broadband savior

Pierce and his wife have a daughter with special needs, and his wife's parents moved in with them into the new house. Pierce's mother-in-law works from home and needed fast Internet service.

Luckily, this story has a relatively happy ending, thanks to a municipal broadband provider. After finding out that Charter would only provide service in exchange for $16,000, Pierce learned about NCATS, or Newaygo County Advanced Technology Services, a broadband network operated by the local school district.

The service is wireless and the speeds don't match Charter's, but it has been good enough for Pierce and his family.

"Wireless Broadband was implemented due to a growing demand for broadband services in Newaygo County," NCATS says on its website. "Wireless Internet has become a community project to offer low-latency, high-throughput resources to those homes and businesses outside the reach of traditional services."

Additionally, NCATS says it "is a publicly owned self-sustained network paid through its subscribed members."

NCATS required Pierce to pay for construction costs, but it was just a fraction of what Charter demanded. A 50-foot tower had to be installed on his property to receive the network's wireless signal. NCATS had a used tower, and it charged Pierce $1,300 for the tower and installation.

Ethernet runs from a receiver at the top of the tower to Pierce's home, delivering speeds of 20Mbps down and 3Mbps up for about $70 a month. Those speeds lag slightly behind today's federal broadband standard, "but it's completely consistent," Pierce said. "We had service from Comcast [at our previous home] and we had 50 or 70Mbps. The 20 we have here almost seems better."

If not for NCATS, "we would have had to pay Charter, there's no question," Pierce said. Cellular service or satellite wouldn't have provided the reliability, low latency, and data allotments that the family needs. NCATS service includes unlimited data.

Pierce also thinks that using a public Internet option will shield him from negative effects caused by the repeal of net neutrality rules. With the Federal Communications Commission regulations being eliminated, "a lot of bad things could happen in our area because of lack of providers," he said. But as an NCATS customer, "I feel pretty immune."

State laws limit Internet options

Pierce had talked to local government officials about his situation, but there was nothing they could do to compel Charter to extend its network to his house. One obstacle is Michigan's Uniform Video Services Local Franchise Act, which prohibits localities from imposing universal service requirements that force cable companies to build their networks out to all homes.

Even though cable companies don't provide service to everyone in any given city or town, the industry has fought against the expansion of municipal broadband providers that could fill in the gaps. About 20 states have laws restricting city- or town-run Internet services.

Michigan is one of those states, with a law that requires public entities to seek bids before providing telecom services and lets them move forward only if they receive fewer than three qualified bids. The law also prevents public entities from providing telecom services outside their boundaries.

Luckily, that law didn't stop NCATS from building its network or from providing service to the Pierces.

"If [NCATS] didn't exist, we would be in a really bad place," Pierce said.

Disclosure: The Advance/Newhouse Partnership, which owns 13 percent of Charter, is part of Advance Publications. Advance Publications owns Condé Nast, which owns Ars Technica.

reader comments

264