Steve Jobs, Theranos' Elizabeth Holmes, and when the 'reality distortion field' fails

The disgraced Theranos founder modeled herself after Steve Jobs, in everything from speaking style to wardrobe. But, as an acclaimed new book about the debacle shows, Jobs-like vision couldn't mask a product that didn't work.

Throughout the very public rise and fall of the blood testing startup Theranos, the company's young founder, Elizabeth Holmes, was never shy about declaring Steve Jobs her role model.

Like Jobs, Holmes dropped out of college and set off for Silicon Valley with dreams of making products that changed the world. Like Jobs, Holmes founded a tech company at an uncommonly young age. Like Jobs, Holmes spoke with a deep voice and favored black turtlenecks. In 2015, Holmes appeared on the cover of the business magazine Inc., next to the words "The Next Steve Jobs."

Unlike Jobs, however, Holmes wasn't able to actually create a product that could change the world. Or even one that worked at all.

Elizabeth Holmes has surrendered to the FBI and faces 20 years in prison. A long way down from this @Inc cover a few years back..https://t.co/AwEwmeCsVJ pic.twitter.com/q0f5ugfs9e

— Natalie Novick (@NNovick) June 16, 2018

Not long after that magazine cover, Theranos' product was proven as a fraud, and Holmes and her company president/romantic partner Ramesh "Sunny" Balwani were indicted last month on federal charges, with Holmes herself facing nine counts of wire fraud and two counts of conspiracy to commit wire fraud.

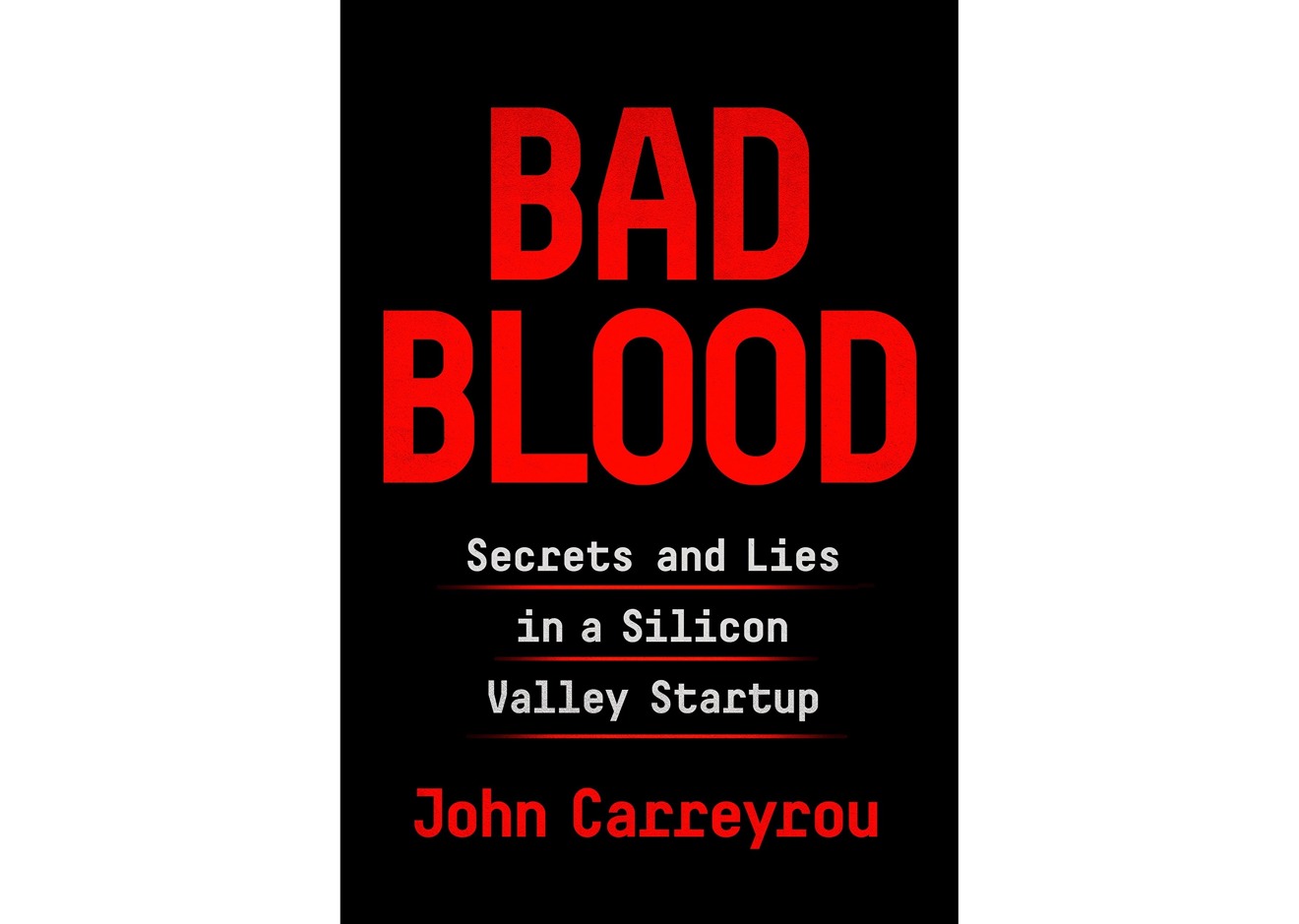

Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley startup, an acclaimed, bestselling new book by John Carreyrou — the Wall Street Journal reporter who broke the story of the company's fraud — delivers the blow-by-blow of Theranos' making and unmaking. And it also shows that Apple had an even greater influence on Theranos than originally thought.

What Theranos said it was

Theranos was founded in 2003 by Holmes, who was only 19 years old at the time and had dropped out of Stanford. The long-term goal of the company was to create a machine that could test blood, with the prick of a finger, and provide faster and more complete results than what is currently available from testing labs.

The company pursued this mission for years. They grew slowly at first, but eventually raised serious amounts of venture capital, which at one point valued the company at $9 billion. Holmes' on-paper net worth at one point was in the billions as well. Theranos partnered with drug companies and retailers — including Walgreens — and was for a time the toast of the tech media, with Holmes appearing on numerous magazine covers.

Theranos later attracted a board that consisted of various establishment luminaries, including former Secretaries of State Henry Kissinger and George Shultz, as well as now-Secretary of Defense James Mattis. Rupert Murdoch and the Walton family, founders of Walmart, and another current cabinet member, education secretary Betsy DeVos, were among the nine-figure investors.

Theranos blew it with their magic blood machines, but the biotech world is looking up. https://t.co/EXK64mmZED pic.twitter.com/maPU652wRz

— WIRED (@WIRED) October 28, 2016

The problem was, in all of those years, Theranos never actually delivered the technology that it promised. It made two different versions of its machine, neither of which worked reliably, to the point where the company ended up doing most of its tests on machines it bought from Siemens. For years, Holmes and the company lied to investors, partners, their own board and the press about what the product could do.

Theranos was operated with draconian security. Personal communications were spied on, leading to a constant atmosphere of fear and distrust that led to massive turnover. Dissenters were purged, and investors were lied to. Employees suspected of talking to the media where followed and threatened by a legal team led by the famous attorney David Boies, who himself owned a stake in the company.

Meanwhile, Theranos perpetuated the fraud by making a point of both using venture capital firms and hiring board members who weren't sophisticated about blood testing or even health care at all.

The fraud continued for a number of years, until Carreyrou — relying on multiple ex-employees as sources — broke the story in the Journal in late 2015. In a surprising moment of moral courage Rupert Murdoch, the owner of the newspaper and a man who had himself invested in Theranos, rejected a personal, in-person appeal from Holmes to block the publication of Carreyrou's first piece.

Murdoch refused even though the collapse of Theranos would cause Murdoch to personally lose hundreds of millions of dollars. Holmes, who had turned out all interview requests from the reporter, met with Murdoch in the same building and at the same time that Carreyrou was in the newsroom, finishing up the story.

The Theranos fraud was insidious not only in that it purloined a lot of people's money. It also spread false hope about nonexistent medical breakthroughs, and even stood to put lives in danger. Providing patients with inaccurate blood test results, as Theranos did as part of multiple pilot programs, had the potential for catastrophic medical consequences.

A heavy Apple influence

The book makes even clearer than before just how much of an influence Apple and Steve Jobs had on Holmes and Theranos.

Holmes, Bad Blood writes in a chapter called "Apple Envy," referred early on to the Theranos system as "the iPod of health care," and predicted that one day the machine would be found in every household in the country.

In 2007, the year of the first iPhone, Theranos poached several employees from Apple. Ana Arriola, a product designer who had been on the iPhone team, joined Theranos that year as the company's chief design architect.

While aesthetics have never been especially important in the medical testing field, Theranos wanted to bring an Apple-like design sensibility to their testing machine. It was Arriola's idea, according to the book, for Holmes to wear Jobs-style black turtlenecks, and the Theranos machines certainly looked passably like something Apple might design.

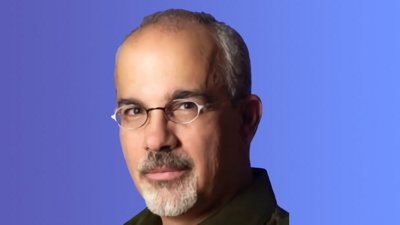

In addition Avie Tevanian, an Apple and NeXT veteran described as "one of Steve Jobs' oldest and closest friends," was a Theranos board member in the company's early days. However, the entire Apple contingent, Tevanian included, quickly grew disillusioned with the company and left one by one within a year.

Arriola, after stints at Sony, Samsung and Facebook, recently joined Microsoft; Tevanian went on to found a "NeXT-themed venture fund."

In October 2011, when Jobs died, Holmes insisted on waving an Apple flag at half mast outside of Theranos' offices. When no one was able to find an Apple flag, an employee went and had one made, as work "came to a standstill" while Holmes waited for the flag to arrive.

Holmes, for awhile after that, took to referring to Jobs as "Steve" and told one employee that she suspected Jobs was a believer in 9/11 conspiracy theories, as he had allowed a documentary about them to be sold in the iTunes Store. She would even name one of the in-development testing machines the "4S," after the iPhone model that had come out that fall.

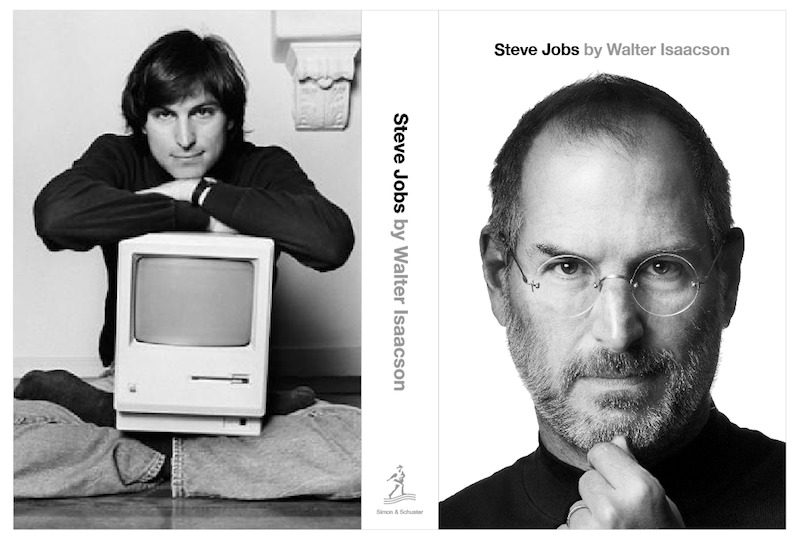

Later that year, Carreyrou writes, Holmes began "borrowing behaviors and management techniques" attributed to Jobs in Walter Isaacson's authorized biography. The book was published weeks after Jobs' death and Holmes and many other Theranos employees were reading at the time.

People in the business world collecting wisdom and advice from that book was not exactly a rare phenomenon at that particular point in time, but Holmes took it further than most. It got to the point where employees "could pinpoint which chapter she was on based on which period of Jobs' career she was impersonating," according to Bad Blood.

In 2012, Theranos brought in Chiat/Day, the advertising agency responsible for some of Apple's most iconic ad campaigns, to handle its account. Theranos paid the agency an annual retainer of $6 million, and the company would later bring Patrick O'Neill, the company's creative director, in-house.

Apple, against the backdrop of Theranos' implosion, has pushed further into the health space itself, even recently patenting something resembling a blood pressure cuff However, Apple has never promised anything as pie-in-the-sky as instant blood-testing results.

Reality distortion field

Beyond all of that, there was one primary thing Jobs and Holmes had in common. Apple's Bud Tribble said in 1981 that Jobs made use of a "reality distortion field"- a term, derived from a 1960s "Star Trek" episode, that sought to explain Jobs' otherworldly charisma and its inexplicable effect on others.

"Steve has a reality distortion field," Tribble explained to Apple's Andy Hertzfeld. "In his presence, reality is malleable. He can convince anyone of practically anything. It wears off when he's not around, but it makes it hard to have realistic schedules."

The "reality distortion field" was also sometimes used by Jobs against himself, to convince himself that things were going better than they really were.

Holmes, clearly, behaved similarly, even taking it further than Jobs in extending it to the totality of the company's product itself. The book also makes clear that Holmes' charisma was almost Jobs-like, in that she could bring employees, investors and journalists under her spell. Carreyrou gives several examples, but one stands out: Early in the company's history, when the Theranos board had agreed in advance of a meeting to fire her as CEO. But then Holmes showed up at the meeting and talked them out of it.

The "reality distortion field" concept was referenced repeatedly in Isaacson's Jobs biography, which Carreyrou's book established was read by Holmes and many of the other top people at Theranos.

For Holmes, the reality distortion continues. In a Q&A on Reddit last month, Carreyrou said that Holmes "showed up at work on Tuesday. I'm told she continues to feel she did nothing wrong and is planning on taking this to trial. You could say she's in complete denial."

Drawing lessons

The Theranos debacle revealed many things. Most notably, it showed that a great many people in the tech world, from investors to board members to journalists, don't know the first thing about how the products actually work. When Silicon Valley was confronted with a product that, literally, never worked it all, it took more than a decade for the truth to come to light.

Around the time of Jobs' death, a lot of people wanted to tell the story of a "new Steve Jobs," and many in Silicon Valley were taken with the idea of that new Jobs being female, at a time when first companies in tech are led by women. Holmes, though, was clearly not that person; there's a chance there may not ever be one at all.

Apple's legacy has had numerous positive effects, there's no question about that, and a great many products developed by Steve Jobs really have changed the world. But the Theranos story, as demonstrated by Bad Blood, shows that the ideas and attributes of Steve Jobs can also inspire bad actors to spread false hope and perpetuate massive fraud.

Stephen Silver

Stephen Silver

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

Christine McKee

Christine McKee