How the Blind Are Reinventing the iPhone

Maria Rios, 66, woke up at 6am. She got out of bed in her little second floor apartment on the north side of Central Park, and checked her iPhone for the weather. Then she felt around in her closet, where she had marked her navy blue garments with safety pins, to tell them apart from her black ones. In the adjacent room, her roommate Lynette Tatum, 49, picked out a white sweater and dark denim slacks. She used her VizWiz iPhone app to take a photograph and send it to a customer-service rep who lets her know what color the item is.

For the visually impaired community, the introduction of the iPhone in 2007 seemed at first like a disaster -- the standard-bearer of a new generation of smartphones was based on touch screens that had no physical differentiation. It was a flat piece of glass. But soon enough, word started to spread: The iPhone came with a built-in accessibility feature. Still, members of the community were hesitant.

But no more. For its fans and advocates in the visually-impaired community, the iPhone has turned out to be one of the most revolutionary developments since the invention of Braille. That the iPhone and its world of apps have transformed the lives of its visually impaired users may seem counter-intuitive -- but their impact is striking.

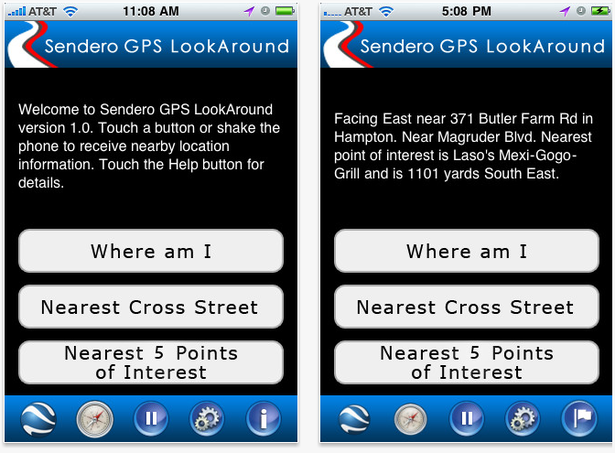

Watching Rios and Tatum navigate the world with the aid of their iPhones is a lesson in the transformative and often unpredictable impacts that technology has on our lives. After getting dressed, they strap on their backpacks, canes in hand, and walk out the door. They can't see the sign someone hung in the elevator, informing them the building is switching to FIOS, but the minute they're outside the fact they can't see is a minor detail. They use Sendero -- "an app made for the blind, by the blind," says Tatum -- an accessible GPS that announces the user's current street, city, cross street, and nearby points of interest. What it's missing, adds Tatum, is a feature that tells you which bus is arriving and what its next stop is. In the meantime they walk a couple of blocks south to catch the M1 downtown.

Rios pulls out coins from her purse and pays the driver. She tells the coins apart by their size and the ridges. Bills are another story -- but there's an app for that. It's called the LookTel Money Reader and with it you can scan the bill you're being handed, instead of depending on the kindness of strangers.

Romeo Edmead, 32, who's been blind since the age of two, is a prominent member of the blind community in New York, taking pride in who he is and all that he can do. He's a guide at the Dialog in The Dark exhibit, a writer for the Matilda Ziegler Magazine for the blind, and an athlete. But he hasn't caught up with the iProducts yet. "It's revolutionary in all that it can do," admits Edmead. "Now, if I want to tell money, I have a standalone device," he demonstrates its size with the palm of his hand. "It's a kind of box you slide the bill into and it tells you what the bill is, but it means carrying something extra. That's inconvenient."

Tatum is what Edmead calls "a techie." She had a previous, failed experience with the Android, which almost made her give up the touch technology. Luckily, she kept her mind open enough to see how those around her are adapting to the iPhone. "I started 'Info share' five years ago, where a group for visually impaired people can share information. A young lady, Eliza, got an iPhone, and she was entranced." The sales representatives at the Verizon store, she says, were very nice and helped her set up her email account and sync her contacts. They didn't know much besides that, and she had to teach them how accessibility is turned on (through Settings.) "They all went 'Whoa!'," she says.

Tatum and Rios happily volunteer to show off all their iPhone can do. "See, I tap it," says Tatum, her iPhone stretched in front of her, "and it started reading out what is on the screen."

Blind people use their iPhones slightly different than the sighted because, well, they can't see what they're tapping on. So instead of pressing down and opening up an app, they can press anywhere on the screen and hear where their finger is. If it's where they want to be, they can double-tap to enter. If it isn't, they'll flick their finger to the right, to the left, towards the top or the bottom, to navigate themselves. The same for the simple "slide to unlock" command.

"We use Audible and it reads for us books that we download from audible.com," Tatum goes on. Each woman is in her respective phone, sliding and flicking and taping, looking for apps. What makes an app stick, they explain, is whether it's practical, accessible, fast, and easy to use. Rios adds that she downloaded a hundred apps by now, but for the most part she'll use an app once or twice and leave it. There are a few, like Sendero, that they use every day. "There's also HeyTell, it's speech texting," explains Tatum. She demonstrates, and manages fairly quickly to record a few words and send them to Maria. Maria receives the message, opens it, and holds her phone to her ear. It works. "There's Dragon Dictation, but that's half baked," says Tatum. "You can speak to it and it turns it into a written text you can then send over." There's also HopStop. "It's completely accessible, you put in your destination and it tells you what trains to take and exactly how to get there."

Chalkias, Tatum's colleague, is not only an iPhone advocate who breezes through the device faster than a baby with an iPad, he also gives private lessons to people of all ages on how to use it. He has found that people, young and old, who can use a computer, are familiar with the desktop environment, and can type, have an easier transition to the touchscreen. "The first thing I teach is the layout," he explains. "They have to understand it's a grid, four by four [apps], they need to understand the dock, the status bar, how to unlock the screen.It's a new language, it means moving from buttons to no buttons, and it means relying completely on audio cues, so it takes time to adjust. The name iPhone is misleading -- it's more of a computer than a phone."

Siri, the highly acclaimed feature of the iPhone 4S, isn't the answer to everyone's prayers, in his view. It's a nice shtick, but it's not always compatible with the voice over feature. "She'll hear what you're saying, explains Chalkias, "but either not respond or her answer will appear on the screen and you'll still have to tap it to hear the response, so there are still some glitches."

Tatum and Rios mention that in the future they'd like their device to describe to them what's on the street as they're walking down -- Toys "R" Us or CVS. It would be great if the phone could vibrate anytime they are close to one. There should be an app that inform thems of construction sites: Even the accessible GPS apps don't mention those. They would also like an app that reads out restaurant menus, and a navigation app that works indoors.

People like Nektarios Paisios, 30, are the ones who can make those wishes come true. Paisios, a Computer Science student from Cyprus, moved to New York four and half year ago to work on his dissertation. He went blind at four years of age, and is working on a number of iPhone apps that could potentially solve some of the blind community's problems with the device. One of them is an indoor GPS.

"One of the biggest concerns of the blind community is finding their way around independently," he says. "You can find an address, but what if you get someplace and you have nobody to help you find your way around the building?" His solution, still in the works, will attempt to sketch a map of the building based on previous routes taken within, and the strength of the wireless signals bouncing from the different sources. It'll also take into consideration the pace and number of steps a person takes from one point to the next. If a blind person were to arrive to a hotel, he'd only need to be shown to his room once. The iPhone will remember the way for him, and navigate him back and forth from the room to the lobby.

Another app Paisios is working on is a more elaborate form of VizWiz, the app that tells the person what color is the shirt he is about to wear. For people like him who have no recollection of color ("yellow means ripe, because yellow bananas are ripe"), it doesn't mean much that the shirt he is pointing to is green. He'd like a stylist app to tell him what this green goes with, so he can know which color pants to put on. It'll also be able to tell more intricate designs. "What if people want to be fashionable?" he asks earnestly.

Yet for all that technology has helped achieve, many in the blind community fear it might result in illiteracy in the generations to come. "I think the technology that's coming out right now is wonderful," says Chalkias,"but I also think it's dumbing us down because it's making everything so easy. I have a lot of teens who have speech technology and they don't know how to spell, and it's horrifying to see that." Rios has encountered the same problem. She is an administrative assistant at the music school of Lighthouse International "an organization dedicated to overcoming vision impairment," based in Manhattan, and a tutor at CCVIP who helps Maria with teenagers. "Even now I come in contact with kids who can't spell," she says. "Young adults don't read Braille because they have screen readers who read for them."

"I definitely think there's benefits to this technology" Chalkias says. ''But if it keeps getting easier we're just going to be a society of idiots that can't do anything except tell our computers what to do for us."