Here's a question you don't often hear asked: whatever happened to Microsoft? To many people, it will seem a silly question. Microsoft, they point out, is still around – with a vengeance. It's a huge company worth $250bn (£160bn) that employs 94,000 people worldwide and earns vast profits. (OK, it made a loss last quarter for the first time in its history, but that's because it had to write off $6bn it blew in 2007 on a company called aQuantive which turned out to be a turkey.) Microsoft dominates the market for PC operating systems and Office software, products that are still licences to print money: its Xbox game console sweeps all before it; its server software is a big seller in the corporate world. In 2012, the company's net revenues totalled $74bn.

Sure, there are some flies in the ointment. Microsoft's search engine, Bing, has failed to break Google's stranglehold on search. The company's repeated attempts to break into the smartphone market have been failures, and its new partnership with Nokia hasn't changed that. Its effort to get into the music business with the Zune player (remember that?) turned out to be an embarrassing farce.

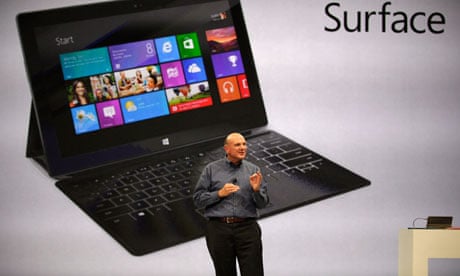

As far as social networking is concerned, Microsoft's modest shareholding in Facebook represents its only successful foray into that territory. It has zero presence in the tablet business (though it's been making brave noises about a forthcoming product called Surface). And its share price has been flat for as long as I can remember.

But when you set all these failures against the money pumps that are the Windows and Office franchises, it's hard to avoid the conclusion that Microsoft's doing just fine. Besides, its products are so deeply interwoven with the IT systems of governments and corporations round the world (just think of the 750,000 Windows machines in the NHS and UK government departments, for example) that Microsoft is one of those enterprises that is – to borrow a phrase – too big to fail.

So why does it remind me of General Motors around the time that Toyota arrived in the US automobile market? This thought was triggered by an astonishing statistic I came across in an article by Kurt Eichenwald in Vanity Fair. It is this: Apple's iPhone now brings in more revenue than all of Microsoft's products. In the quarter ended 31 March 2012, the iPhone had sales of $22.7bn. In the same period, Microsoft earned $17.4bn from everything it sold. So a single Apple product, which didn't exist five years ago, had higher sales than everything Microsoft has to offer.

Cue the predictable storm of protests that this is a misleading comparison: apples and bananas and all that. Smartphones are not office systems, you can't run the NHS on iPhones, blah-de-blah. All true. But don't let those soothing rationalisations distract you, because implicit in the statistic highlighted by Eichenwald are two salutary, general lessons.

The first is about the speed of change in this industry. It's not just that the iPhone (and the iPad) came from nowhere and created a market that nobody, including Microsoft, took seriously, it's that it happened in under five years. And that it propelled a company (Apple) that was a corporate zombie 15 years ago into the most valuable company in the world, with a current market cap of $590bn.

The second lesson is about how hard it is for dominant companies to stay innovative in such a fast-changing environment. Microsoft, remember, was once an incredibly rich, smart, agile, innovative, competitive and aggressive company. Today, only the cash reserves and the aggression, personified by its current CEO, Steve Ballmer, remain.

The question Eichenwald set out to answer was this: how did Microsoft change from being the lean, mean machine created by Bill Gates and Paul Allen into the sleepy behemoth it is today? In seeking an answer, he interviewed a lot of ex-Microsoft employees. They told a dismal tale of opportunities missed, innovations squashed and talented people demotivated by the corporate ethos of a maturing organisation.

What it basically came down to is this: in the start-up phase of a tech company, people are collaborative and technically innovative because a successful IPO means that they'll all get rich. But once the share price flattens out and the company grows, stock options become less valuable (or even worthless) and then the only way to get on is to play managerial games and organisational politics. Bureaucratisation takes hold and innovation takes second place. Eventually, the point is reached when everything is designed or decided by committee, and... well, you can guess the rest.

And – to return to my original question – that's what became of Microsoft.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion