Bob Quinn, one of the top AT&T lobbyists ("Senior Vice President-Federal Regulatory") in a company famous for lobbyists, must have drawn the short straw at the office staff meeting this week, because he got a truly unenviable job. Quinn's task was to explain to the world how AT&T's plan to keep blocking FaceTime video chats on some data plans but to unblock it on others was a good thing for customers, how AT&T was in "a learning mode," and—most importantly—why the decision was absolutely, completely legal despite what the unwashed peasants in "public advocacy" work would have you believe.

So Quinn walked down the hall to the closet next to the photocopier and pulled out something reserved for just such an occasion: the company's sole suit of adamantine armor, fortified against flame attacks by a special concoction distilled from the rage of 10,000 Internet commenters. (We are, admittedly, hypothesizing a bit at this point.) Bold Sir Quinn donned the suit and sallied forth to his desk, where he sharpened his quill pen and churned out a corporate blog post on "enabling" FaceTime for AT&T users.

In it, Quinn pointed out that AT&T's serfs customers could continue to use FaceTime over WiFi. With iOS 6, they can soon use FaceTime over the cell network, too, but only with certain data plans. On other plans, FaceTime wouldn't work. The restrictions apply only to FaceTime, however; Quinn even suggests that aggrieved users go out and download any other video chat app from the App Store—and they can run it on any data plan without problems.

The distinctions being drawn seem bizarre and arbitrary to many customers who argue that data is data—I paid for it and should control what I use it on, not AT&T. It's even stranger because AT&T isn't targeting "video chat" apps with its restriction; it is only targeting FaceTime.

What is going on here?

She canna handle the data, Captain!

Essentially, AT&T is counting on customer ignorance/laziness to save it from a data glut. The company knows that most cell phone users will favor the pre-installed apps, possibly adding a few more like Angry Birds, but largely not going out of their way to test and use other video chat apps (which generally require the people at the other end of the line to have the same app installed).

So the company can be generous when it comes to "downloaded" apps, but it fears that tearing down the wall around something like FaceTime would simply create too much data to handle. As Quinn finally admits near the end of the post, the decision is all about AT&T's "overriding concern for the impact this expansion may have on our network and the overall customer experience." Translation: we're afraid it would melt our network.

So much for the argument; the real question is, "Can this be legal?" The main thrust of Quinn's post was that it is legal because AT&T told people what it planned to do in advance. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC), in what was widely considered a weaker than weak-tea "open Internet" order in late 2010, did mandate transparency around network management—which is why AT&T had to announce the policy in the first place.

"Our policies regarding FaceTime will be fully transparent to all consumers, and no one has argued to the contrary," wrote Quinn. "There is no transparency issue here."

"Ah," protest the serfs, gathering around the baronial estate with pitchforks in hand, "but even under the open Internet order AT&T can't just block apps, right? This is an outrage!"

But the anger just serves to remind us how weak the rules are; blocking apps is indeed just fine... with one notable exception.

The rules

One of the ironies of FCC rulemaking is that, under Republican leadership generally hostile to the idea of legally enforced net neutrality, the FCC actually passed a 2005 "policy statement" (PDF) outlining four freedoms all Internet users could expect. Number three read:

To encourage broadband deployment and preserve and promote the open and interconnected nature of the public Internet, consumers are entitled to run applications and use services of their choice, subject to the needs of law enforcement.

The principles were all subject to "reasonable network management," but it soon became clear that throttling or blocking particular apps didn't qualify as "reasonable." The FCC soon went after Comcast for BitTorrent interference and forced the company to change its ways (Comcast adopted a much improved system that focused on the heaviest local users at periods of actual, local congestion, rather than picking apps or protocols to burn at the stake.) Under this regime, which applied to wireless and wired networks, AT&T's current FaceTime monkey business would have violated the rules.

But Comcast sued the FCC over the issue and won, arguing that the policy statement had never been a set of "rules" and that the FCC wouldn't have the authority to make such rules anyway. So, under a Democratic FCC led by someone who promised to implement net neutrality rules, the agency adopted a strangely bifurcated order (PDF) that applied some of the same principles to wired networks—but gave wireless a huge pass (start reading at paragraph 93 for the wireless rules).

Although the FCC's final order said things like, "there is one Internet, which should remain open for consumers and innovators alike, although it may be accessed through different technologies and services," it actually let wireless operators do just about anything they liked, including blocking most apps.

The FCC did carve out one restriction on blocking apps, however: companies can't do so to squelch competition. Here's the official rule:

A person engaged in the provision of mobile broadband Internet access service, insofar as such person is so engaged, shall not block consumers from accessing lawful websites, subject to reasonable network management; nor shall such person block applications that compete with the provider’s voice or video telephony services, subject to reasonable network management.

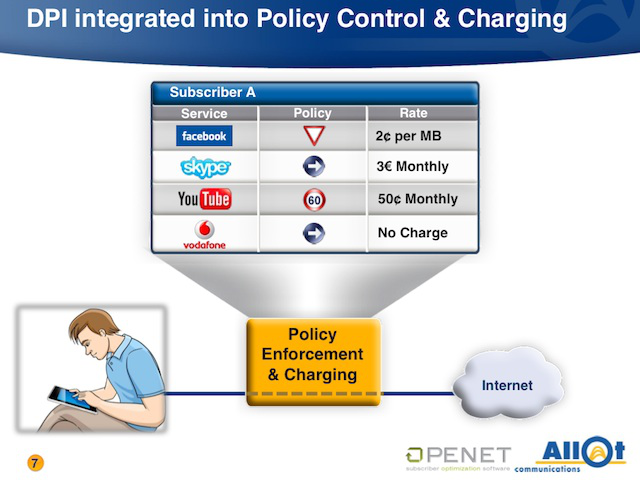

The FCC concerns behind the rule aren't theoretical; wireless operators like KPN, the incumbent telco in the Netherlands, have already blocked apps like WhatsApp (an instant messaging app) and Skype on the straightforward reasoning that these apps are bad for business by replacing texting and voice calls that might otherwise rack up separate fees. (The blocking was so egregious that the Netherlands passed the world's second net neutrality law in response.)

AT&T insists that FaceTime doesn't compete with its own services. As Quinn put it, "AT&T does not have a similar preloaded video chat app that competes with FaceTime or any other preloaded video chat application."

And at this point, suddenly, we have entered Lawyer Land, where the construction of sentences matters far more than everyone but your grade school grammar teacher (remember "diagramming"?) ever thought it would. The order prohibits AT&T from blocking apps that compete with its own "voice or video telephony services." AT&T wants to interpret this as saying it would only apply to an AT&T video app, but that's not what the rule actually says. One could certainly make the case that FaceTime in fact competes with even AT&T's basic voice chat service (Quinn wants to talk about "apps," which AT&T doesn't have, but the order is talking about "services").

Public Knowledge makes this exact argument: "Many people use apps like FaceTime, Skype, and ooVoo instead of making voice calls. In many respects these apps are more convenient than traditional calling. And by using these apps, consumers can save money on international calling charges, conference call services, and in other ways. There's no doubt that these apps are a competitive threat to AT&T's voice service."

Free Press is just as upset, writing, "Though it’s trying its best to hide it, the truth is that AT&T’s motivation here is to prop up its slowly declining voice and text revenue streams, which are expensive services that the open internet is making obsolete. If AT&T can weaken the FCC’s Net Neutrality protections at the same time, well that’s a bonus. The decision to block FaceTime likely will not be the last anti-consumer thing AT&T attempts as it tries to reassert its control over the communications ecosystem that the open Internet pried away long ago."

But what if AT&T isn't technically "blocking" anything at all?

"Blocking" vs. "exerting influence"

The language surrounding this entire issue is quite strange, with AT&T going on about how the FCC rules don't apply to "preloaded apps" (the order says nothing about preloaded apps). Apple and AT&T have in the past danced around the issue of exactly how the FaceTime restriction will be implemented—is AT&T going to block network traffic, or did it lean on Apple to make sure that traffic never even entered the network in the first place?

In the past, Apple coded its FaceTime app so as to work only over WiFi; that will now change with iOS 6. Sprint has already made clear that FaceTime will then be available to all users of its cell network, but AT&T wants to open the barn door only a crack. Perhaps it has leaned on Apple to build the barn-door-controller code into FaceTime itself, sparing AT&T the problem of trying to filter its network.

We're guessing that Apple has, in fact, gone along with this scheme, which is probably why AT&T keeps stressing that preloaded apps aren't required to do anything in particular. So long as AT&T or other carriers can convince Apple to alter its FaceTime code, the telco never actually has to get into the messy issue of identifying and blocking traffic in the first place. This helps explain what otherwise seems like an odd pair of sentences:

Although the rules don’t require it, some preloaded apps are available without charge on phones sold by AT&T, including FaceTime, but subject to some reasonable restrictions. To date, all of the preloaded video chat applications on the phones we sell, including FaceTime, have been limited to Wi-Fi.

The rules may forbid AT&T from blocking an app—but they don't require any specific app to use cell connections. So long as Apple made the change, AT&T seems to believe it's in the clear.

Either way, groups like Public Knowledge still see red.

"We don't know why Apple chose not to enable cellular FaceTime earlier," wrote John Bergmayer, a senior staff attorney. "But now that every other US iPhone carrier besides AT&T will be offering cellular FaceTime on a nondiscriminatory basis, it is reasonable to assume that AT&T's demands were holding it back for everyone. No carrier should be able to dictate to Apple or any other handset manufacturer what features they may include on their phones."

reader comments

142