Steve Jobs's dire legacy: Devastating bad taste

"We have always been shameless about stealing great ideas" — Steve Jobs, Triumph of the Nerds, 1996

"I'm going to destroy Android, because it's a stolen product. I'm willing to go thermonuclear war on this" — Steve Jobs, Steve Jobs, 2011

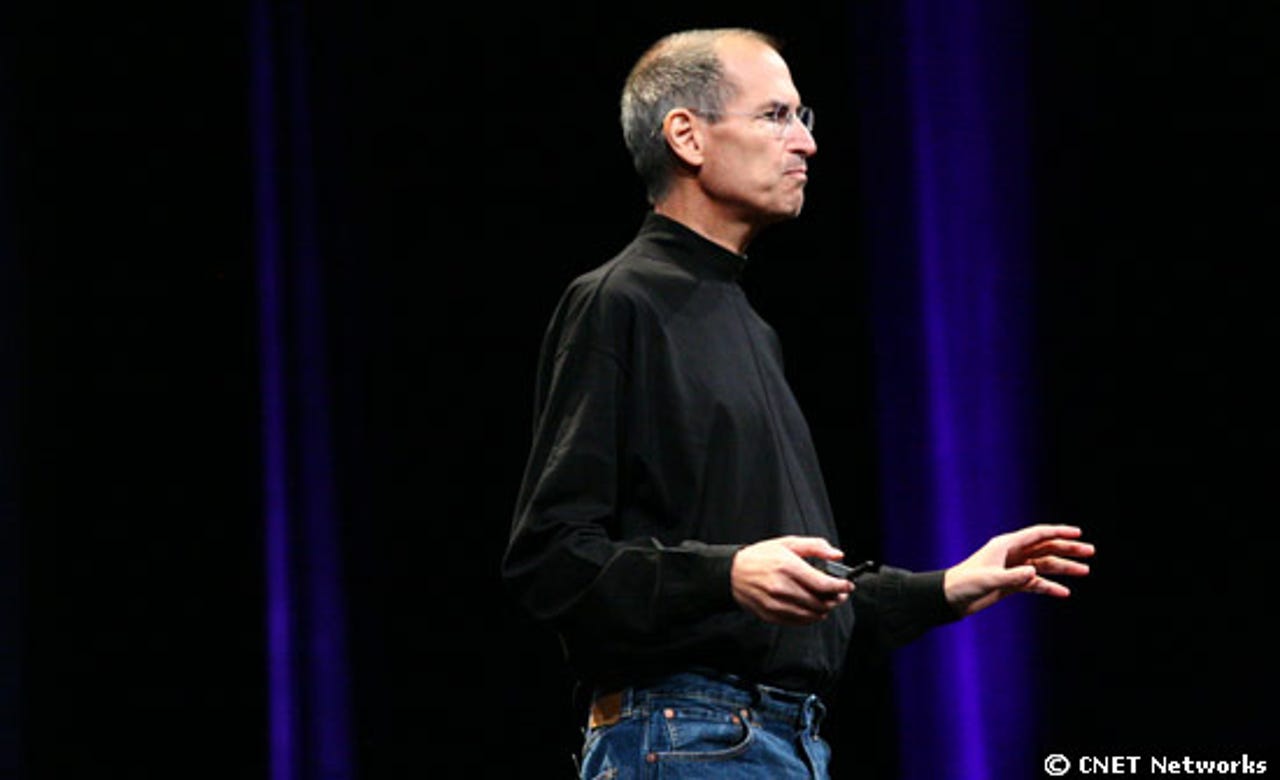

What made the Jobs of 2011 so different from the 1996 model? Power. Apple was in trouble in 1996, losing its way in a welter of bad products and worse decisions. Jobs was at NeXT, contemplating the failure of his workstation strategy.

But in 1997, Apple bought NeXT and hired Jobs as a consultant. By 2011, Apple was one of the most powerful tech companies in the world, fully equipped with corporate nukes, and Jobs was its saviour and untouchable leader. He was also dying.

Dying leaders threatening nuclear war on rivals are rarely good news. They have no reason to lie.

Take a moment and let Jobs's threat sink in. This is a man who once excoriated Microsoft about its lack of taste: for him to use nuclear war as a metaphor is a horrible irony. For most of the past 70 years, it has been the single most plausible mechanism for global destruction — a state of such chaos, pain and inhumanity that causing it could only be contemplated as the act of a madman.

We have seen nuclear war just once, in the closing days of the Pacific theatre in World War II. It was not one, but two brutal strikes against Japan, a broken country already close to suing for peace. President Truman took the decision to forestall Soviet aggression: an act whose morality, even in the context of that cruel conflict, is questionable.

But in one respect, it did its job. The demonstration of the power of nuclear weaponry stamped its consequences firmly in the global mind. The point of having such weapons was not to use them, but to stop others using them.

Lost leader

Apple, however, is following the diktats of its lost leader. It is using its cash and patents — the nuclear weaponry of large corporations — while, inevitably, claiming that this is the application of natural justice against a great wrong.

The facts of thermonuclear war are stark. The collateral damage to everyone, regardless of their active involvement in the conflict, is tremendous. The long-term consequences are incalculable.

It is extraordinarily distasteful to talk of the mobile phone business in such terms. That Jobs, a child of the Californian Cold War counter-culture, should have chosen it as his metaphor is telling. For he will have known that such actions are not necessary to guarantee victory, let alone survival.

Android, after all, is guilty at worst of nothing more than the sort of behaviour that Jobs himself once gloried in — back in the days before he had nukes.

Yet he pushed the button. He may have been comfortable with the consequences for consumers, for the economy, for the ecosystems that drive innovation, of closing down competition.

The rest of us may think differently.