There has been a lot of talk lately about Apple's new user tracking system introduced with iOS 6—but certainly not from Apple. The company has stayed largely mum on the user side when it comes to how it's helping app makers and advertisers track information about iPhone, iPad, and iPod touch users, leading some around the Web to panic over privacy. As usual, the actual situation is more nuanced than what some would have you believe, but it's worth being educated about what's going on so you can decide how to handle your own privacy decisions.

We've been receiving reader questions lately about Apple's recent changes—here are some answers to the most common questions.

What was the UDID and why did Apple stop using it?

The UDID, or Unique Device Identifier, is a 40-character string that uniquely identifies a specific iOS device, similar to a serial number. The UDID has been used for many things in the past, including connecting your device to an iOS Developer account for iOS beta releases, connecting your device to your Apple ID so that you can reinstall App Store purchases or re-download music, connecting your device to iMessage so you can receive messages at multiple locations, and so on.

Those are all still legitimate uses for the UDID—mainly because it's Apple who is using that information. But until the release of iOS 6 in September, UDIDs were also used by advertisers and third-party developers in order to collect user data—this was mostly so they could offer targeted advertisements, but some also used the UDID for their own Game-Center-like networks.

We wrote an Ask Ars about the UDID back in September of 2012 with even more details about its uses and why Apple decided to deprecate it—at least when it comes to third parties. But the general gist is that although the UDID could have been used as a semi-anonymous token to track users, many developers ended up connecting UDIDs with users' real names, addresses, phone numbers, and other information. And when that data was correlated together, it could have been used to actually identify a particular user—in fact, security researchers issued a paper in 2010 showing that plenty of third-party apps transmitted users' UDIDs back to their own servers along with personally identifying information.

That's part of why Apple decided to deprecate the use of UDIDs with the release of iOS 5 in October of 2011, and started rejecting apps that made use of the UDID earlier this year. But Apple's action in discouraging the use of UDIDs came too late to avoid a UDID-related privacy nightmare.

Anonymous-offshoot group AntiSec released a list of one million UDIDs in September, with many attached to full names, cell phone numbers, and home addresses. At the time, AntiSec claimed the list came from a hacked FBI laptop, but that claim was soon debunked by digital publishing firm BlueToad, who verified that the list came from its own hacked system. BlueToad itself is not a widely recognized name, but it created apps for other companies, such as Variety Magazine, Modern Luxury, Arhaus, and others—like other publishers, it too collected UDIDs and personal information from the users of those apps.

AntiSec's release of the UDID list came nearly a year after Apple first told developers it was deprecating the use of the UDID by third parties, but the incident shows why app makers and advertisers shouldn't have had access to the UDID in the first place. There was no way for users to disassociate the UDID from their devices or turn off any kind of tracking, which is why it's a good thing that it's no longer in use.

Now I hear there's something new. Did Apple lie about getting out of the tracking game?

This is the area where there's been some misinformation floating around. By the wording of this Slashdot post and its accompanying post on Sophos, you might have been led to believe that Apple had sworn off user tracking, only to slyly sneak it back in. "Apple got caught with its hand in the cookie jar… Enough is enough, right? Well, maybe not," wrote Sophos this week.

That's not exactly the case. Ever since Apple began rejecting apps that made use of the UDID earlier this year, it had been suggested that the company was working on offering some other way for developers to track users. Rumors about the new identifier began circulating in June—around the same time developers began talking about Apple's new Identifier for Advertising, or IDFA. And in September, when Apple issued a statement over the AntiSec leak, the company publicly acknowledged that a new tracking system was on the way: "[W]ith iOS 6 we introduced a new set of APIs meant to replace the use of the UDID and will soon be banning the use of UDID," Apple spokesperson Natalie Kerris said at the time.

So, it was no secret that the UDID was going to be replaced with something else, and that alternative was expected to be more privacy-conscious. Now that iOS 6 is out and available to the public, the new IDFA is indeed in place, and advertisers have already been using it to track you on your iPad, iPhone, or iPod touch. Surprise!

How does the IDFA differ from the UDID?

Advertisers largely use the two IDs in the same way, but there are a few key differences between them that affect both users and advertisers.

On the user side, the UDID was not something you could control or limit in any way—advertisers who wanted to grab it could easily do so without your permission or knowledge, and there was nothing you could do about it. The IDFA differs from that because you can control it on the user end; if you don't want your browsing habits tracked, you can flip it off (see how in the next question). Additionally, as pointed out by Sophos, the IDFA "can't be traced back to individuals, it merely links a pattern of online behavior with a specific device."

On the advertiser end, the IDFA acts as a persistent cookie that won't be cross-contaminated. This is better for them because if you sell your old iPod touch to someone else and buy a new one, your UDID might change and an advertiser might think you're an entirely different user. (Not to mention that your old UDID is now being used by someone new, so any advertising info that was previously attached to your UDID is now being targeted toward a different person.) Because the IDFA divorces itself from the UDID, it can be reset with a new device and there won't be any crossing of the streams when it comes to ad targeting.

How can I control how the IDFA tracks me?

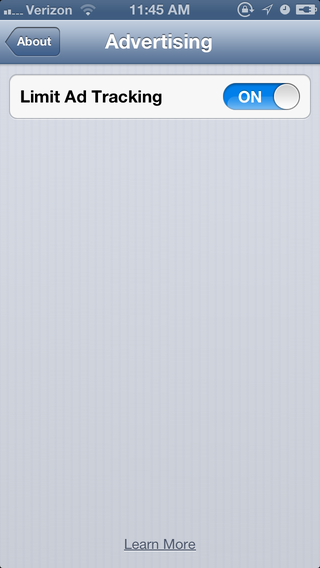

So you don't like targeted ads—that's fair. If you're running iOS 6, the IDFA is turned on by default, but it's easy to turn it off. On your iOS device, go into Settings > General > About > Advertising and flip the "Limit Ad Tracking" switch to "on." It will be set to "off" by default—the wording is somewhat confusing, because it makes you think the ad tracking is off, but actually it means that your limitation of the ad tracking is off. Tricky tricky, Apple.

reader comments

47