How Much Longer Can Tech's Free Party Last?

We're living through a unique time in history, when the most important innovations, created by some of the country's smartest thinkers and hackers, are basically free

Recessions breed innovation. That's a smart lesson to draw from the 20th century.

Alexander J. Field called the 1930s "the most technologically progressive decade of the century." It was the decade that invented the television, popularized the washing machine, and accelerated our railroads.

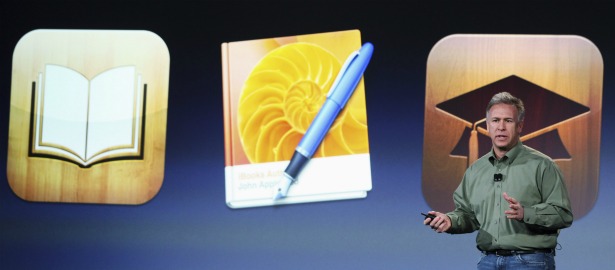

In this Great Recession, some of the most visible innovation has been around smart phones and apps. The first iPhone was released in June 2007, six months before the downturn officially commenced. Since then, the "app economy" has grown into a $20 billion business responsible for more than 450,000 jobs. The recession and slow recovery will be remembered as the time when Twitter went from fringe microblog to publishing powerhouse; when Facebook went from private fascination to public juggernaut; and when Dropbox and Square were born.

But what's distinct about many of these innovations is that, unlike the generation of inventions that came out of the 1930s, they're basically free. Phones cost money, data plans are expensive, and Internet connections aren't cheap. But the software products and smart phones apps that some of this generation's smartest young men and women are dedicated their lives to building cost nothing or next to it. Users might considers that observation obvious. And it is. But it's also really, really weird.

The app economy -- a basically free technology revolution that costs nothing to users except our attention -- happened to arrive as millions of people had very little to pay for new products. It was the perfect tech revolution for the perfect moment: Software being the cheapest means of reaching a wide audience; venture capital firms being hungry for hot new services and apps that used software to capture millions of users; and then dangling somewhere in the distant future, the promise of monetization.

Some of these app companies will make money, either because they get customers to pay, or get advertisers to pay, or get some third party to pay for the customers' information. But many won't.

It's possible that venture capital firms will continue to support apps and software companies until they reach an audience and have to start thinking about making money. After all, inventing an app isn't like inventing the toaster: The first connects on a global platform that already exists (the Internet, the smart phone) and the second requires an expensive and labor intensive global supply chain to build and ship across the world. As a result, you can build a global software product with just a handful of great engineers, which makes it much easier to sell your product for next to nothing.

But it's also possible that as some of the app economy's monetization windows start to close as venture firms turn sober on online and mobile advertising, engineers and entrepreneurs starting a company will have to charge users more (or charge users earlier) for their program. In that case, we'll look back at this period as as unique breath of time when some of the smartest hackers and thinkers worked on innovations that were free to their hundreds of millions of users.

><