Since 2009, it's been possible to develop iOS applications using C# and .NET, courtesy of MonoTouch. But one important detail has always been missing. If you wanted to use Visual Studio—the premier C# and .NET development environment, the one that almost every C# developer calls home—you were out of luck.

With Xamarin 2.0, that all changes. You can now develop and debug apps for the iPhone, iPod touch, and iPad in Visual Studio in Windows. Don't want to use Visual Studio? Xamarin has a new cross-platform IDE, Xamarin Studio. To make apps easier to build, Xamarin now offers a component store, giving Xamarin developers instant access to a range of free and paid pre-built libraries and user interface controls. Topping it all off, there's a new pricing model that starts from free.

I've been taking a look at it for the past few weeks to see how it all works.

The realization of ambition

The company Xamarin rose from the ashes of Novell. When the one-time king of corporate networking was taken over by The Attachmate Group, one of Attachmate's first moves was to lay off large portions of Novell's workforce. Throughout the years, Novell had acquired a range of companies in an effort to move beyond its file and print serving business. Attachmate, however, was only interested in two things: Novell's library of patents and the SUSE Linux business it bought in 2003.

One of the victims of these layoffs was Ximian, another 2003 purchase. Ximian was founded in 1999 by Miguel de Icaza and Nat Friedman in order to develop Linux software for the GNOME desktop environment. One of its core technologies was Mono, a project that sought to implement a compatible, open source implementation of Microsoft's .NET Framework and its C# language.

While at Novell, the Mono team developed a version of Mono for the iPhone (MonoTouch) and another for Android (Mono for Android). These allowed developers to write applications for, respectively, the iPhone and Android devices that used C# and Mono's version of the .NET Framework. It provided .NET developers a familiar language and set of libraries as an alternative to Objective-C on iOS, and Java, on Android. While the underlying Mono was, and is, open source, these additional frameworks were not.

MonoTouch was first released in 2009. Mono for Android came in April 2011. Within a month of the release of the Android product, Attachmate both bought Novell and booted out all the Mono developers.

Though laid off by Attachmate, de Icaza and Friedman were convinced of the value of Mono—in particular, its smartphone variants. The pair immediately formed a new company, Xamarin, to continue the development of Mono. They also outlined a plan to provide a new set of smartphone-oriented frameworks.

This initially appeared problematic. They could not use MonoTouch or Mono for Android as the basis for their work, as these were owned by Novell and now Attachmate. Worse, due to their involvement in the development of MonoTouch and Mono for Android, it would have been difficult to prove they were not using code belonging to those products in their new frameworks.

Ordinarily, one might expect this to turn into a legal quagmire, but it didn't. Attachmate granted Xamarin a perpetual license to use, maintain, and extend the MonoTouch and Mono for Android products. Xamarin wouldn't have to start from scratch, and it wouldn't have to worry about tainting its code with Attachmate-owned intellectual property either.

Xamarin swiftly released maintenance updates for the Mono products, providing continuity for existing users. The group continued to sell and support MonoTouch and Mono for Android as well. Xamarin's first products were, by necessity, somewhat rushed, as the fledgling company needed to get something on the market fast. Mono for Android development could be done in both MonoDevelop, an open source C# IDE, and Visual Studio, the environment that is the natural home for most C# developers. iOS development, however, could only use MonoDevelop.

In spite of these rough edges, the company found an eager audience and grew rapidly. Today it boasts 12,000 paying customers and close to a quarter of a million developers now using the Mono stack. They're producing a wide range of apps, with the major categories being internal use line-of-business apps and games.

Xamarin's underlying goal has been to create the best mobile development experience. The company wants to marry highly productive tools and development environments to easy cross-platform development, while still allowing developers to tap into all the rich underlying capabilities each platform has to offer. Xamarin 2.0 is the first full realization of that ambition.

The first important thing about Xamarin 2.0 is that the awkward naming has been cleaned up. Instead of the weirdly asymmetric MonoTouch and Mono for Android names, the underlying platform is called Xamarin. The iOS and Android variants are called Xamarin.iOS and Xamarin.Android, respectively. There's also a Xamarin.Mac for producing apps for the Mac App Store.

The platform is split into common parts and platform-specific parts. Common ones include the C# language and the .NET Base Class Library, which provides standard functionality such as network connectivity, data structures, file and database access, and threading. These platform-specific parts wrap the libraries and APIs of the underlying platform. For example, Xamarin.iOS gives Xamarin developers access to APIs such as Core Animation and iAd; Xamarin.Android has things like an API for NFC hardware and another for accessing Google Maps.

Also included in these platform-specific parts are all the user interface APIs. The model for Xamarin is that non-UI parts of the application—communicating to remote servers, parsing files and data from networks, storing information persistently, and so on—should be shared across platforms, built using the Base Class Library (BCL). UI parts, however, should be platform-specific to ensure each UI looks and feels correct on its respective platform.

There's also a large set of functionality that's common to smartphone platforms but not covered by the BCL. For example, all smartphone platforms have GPS APIs, camera APIs, and contact APIs. Xamarin has developed a library named Xamarin.Mobile that encompasses this functionality, to allow cross-platform apps to share more code.

iOS development in Windows, for real

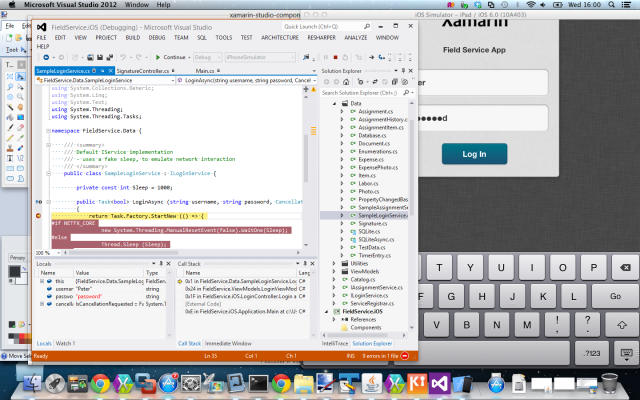

The centerpiece of Xamarin 2.0 is support for Xamarin.iOS in Visual Studio. Xamarin says this was in huge demand, with three-quarters of customers wanting the ability to use Visual Studio for their iOS development. The remarkable part about this is, well, it all just works. Get the software installed and you can create Xamarin.iOS projects in Visual Studio. Visual Studio's usual platform options are extended to include iOS devices, and it gains two special debug targets: the iOS Simulator and a physical iOS device.

Although this is perhaps the most striking feature of Xamarin 2.0, it's also an odd one as there's not actually a whole lot to say about it—because, again, it just works. This is iOS development in real Visual Studio. Visual Studio's key bindings, Visual Studio's text editor, Visual Studio's menus, Visual Studio's autocomplete and IntelliSense—even Visual Studio's debugger—are all provided and work in the usual Visual Studio manner.

Want to use Visual Studio's integration with TFS or the new git integration? You can do that, because you have nearly the full range of Visual Studio features and capabilities available to you. Want to run unit tests with Nunit? Go right ahead. Prefer to use the ReSharper plugin for its richer refactoring and IntelliSense support? That will work just fine. This is truly developing on Visual Studio.

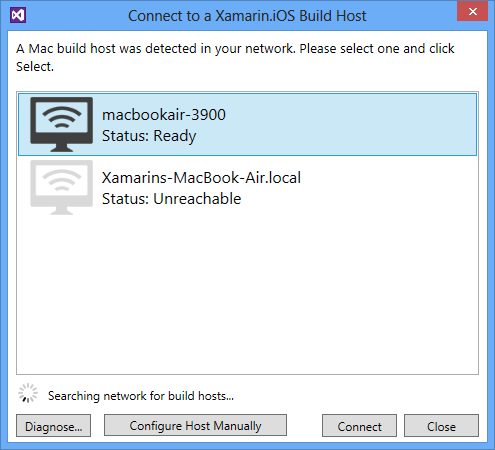

Behind the scenes, things are a little more complicated. The traditional Mono and .NET compilers produced a bytecode called IL (Intermediate Language) which is just-in-time compiled on the end-user's machine. However, this kind of technology is prohibited on iOS. Instead, Xamarin uses an OS X machine to compile its software and deploy it onto hardware. Xamarin development in Visual Studio needs both Windows and OS X available: Visual Studio runs in Windows and it connects over a network to OS X. The OS X machine has the iOS SDK. Visual Studio controls it remotely, using the Mac for all build-related tasks. The programs are actually compiled using Apple's compiler and tools, so they are in every important sense identical to programs written in Objective-C.

The setup I used had everything running on a single system. Visual Studio ran in a virtual machine inside VMware Fusion, with the iOS SDK and Xamarin build components installed on the OS X host. But the two don't have to use the same hardware. If I had a Mac Mini tucked away in a cupboard, that would work too.

The connection between the two was almost seamless. When it worked, it was essentially invisible. I hit ctrl-shift-B to build (or F5 to build, deploy, and debug) and everything happened as expected. The network machinations and remote compilation were invisible. Occasionally I did have some minor upsets where Visual Studio would lose the network connection to the OS X build system, though this may have been some interaction between VMware and the Wi-Fi networks I was using rather than anything to do with Xamarin per se.

That seamless support extended even to the debugger. Set a breakpoint and hit F5 and your app will build, deploy, start executing, and run until it hits the breakpoint. You can then inspect values by using Visual Studio's various debugger panes or hovering the mouse over variables in the text editor. You can change values while the program is paused. You can single step. It offers almost all the functionality that Visual Studio developers have grown to expect, with the same user interface they know and love.

There is one gap. Visual Studio's edit and continue feature that lets you modify code and recompile it without having to restart the program from scratch isn't supported. Given the nature of the compilation and deployment system that's at work behind the scenes, this perhaps isn't altogether surprising.

Deployment for debugging and testing can be on physical hardware or the iOS Simulator that's part of the iOS SDK. Unfortunately, the iOS Simulator isn't made available remotely. It runs only on the OS X desktop. As a result, you'll probably want to make use of VMware's Unity mode (or similar features in other virtualization software) so that both Visual Studio and its debugger and the iOS Simulator can be visible on-screen at the same time.

The result is, well, a little uncanny. It feels wrong to have a virtual iPad up on screen next to Visual Studio. But it works.

There is one other important functional gap. At the moment, Xamarin.iOS for Visual Studio includes no user interface editor. Instead, developers wanting a graphical interface editor must use Interface Builder in Xcode. Xamarin says MonoTouch developers are currently split about 50/50 between those who use Interface Builder and those who build their interfaces entirely in code.

Longer term, Xamarin hopes to fill this gap. Xamarin.Android already has: there's a form designer that produces Android's user interface XML to allow drag-and-drop user interface building. Using Xamarin.Android with Visual Studio also doesn't require a counterpart system for building and deploying, as the Android SDK runs directly under Windows. Xamarin says it intends to provide an iOS experience comparable to the Android one in the longer term.

Although it's difficult to imagine the OS X dependency ever going away due to the nature of the iOS SDK and the desire to keep Apple on-side and happy, an integrated forms designer within Visual Studio is a likely future development. In the meantime, VMware's unity mode again enables the Apple software to be used side-by-side with the Microsoft software.

There's one other limitation developers need to be aware of, this time imposed by Microsoft (and applicable to both Android and iOS development). You can't use the free Express version of Visual Studio with Xamarin because Microsoft prohibits the use of most extensions and add-ins in Visual Studio Express.

reader comments

188