I’ve written a couple of times (here and here) for Insiders about smartphone upgrade cycles in the US. Today, I want to broaden the discussion a little and talk about something slightly different. This is something I touched on very briefly on the podcast this past week, but I’ll elaborate on it here. What’s becoming clear is we’re not just seeing a subtle lengthening of the smartphone upgrade cycle. We could start seeing a completely new behavior around smartphone upgrades which is much harder to predict than in the past.

The US Experience – Installment Plans Loosen Cycles

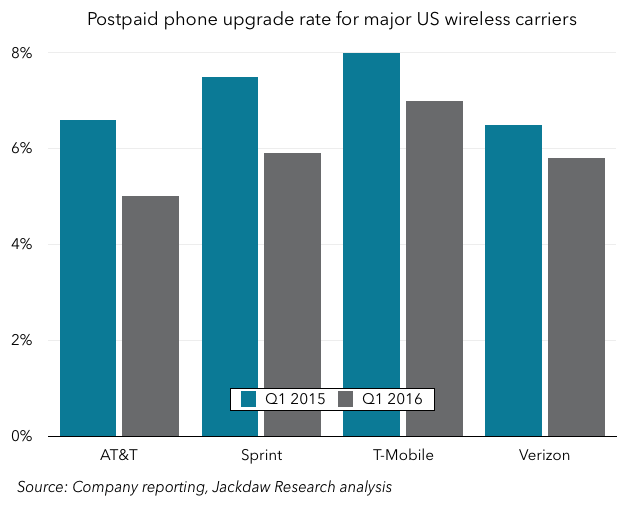

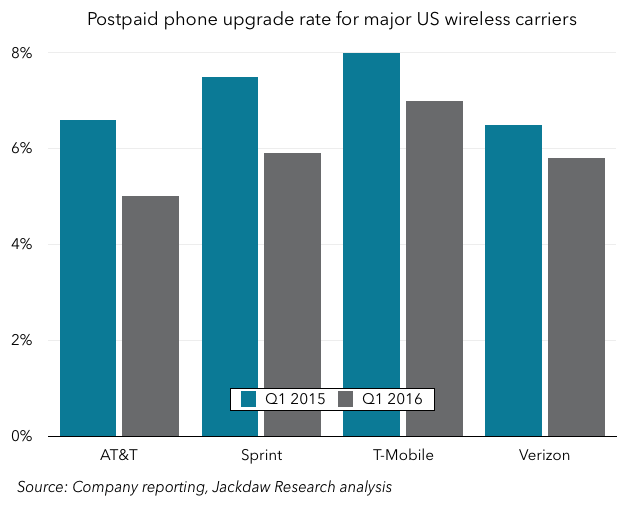

The focus of what I’ve written about in the past has been the specifics of the US wireless market, where the major carriers regularly report the percentage of their customers that upgrade their devices in any given quarter. The first of the two pieces linked above noted the introduction of installment plans for buying devices seemed to be accelerating the rate at which people upgraded their devices, based on the evidence at that point. The second though, noted the effect was becoming more complex than that and there was a discrepancy between two groups within the US carriers — one set seeing accelerated upgrades and the other, slower cycles. With another quarter of reporting under their belts, the carriers are now showing a more consistent trend in favor of longer upgrade cycles:

This past quarter, every one of the four major US wireless carriers saw a lower upgrade rate than a year earlier. AT&T and Sprint saw upgrade rates 1.6 percentage points lower year on year while, at T-Mobile and Verizon, the difference was one percentage point and 0.7 respectively. That makes for an average of 1.2 percentage points fewer upgrades in the quarter which, in turn, would mean over five percentage points fewer in the course of a year. Based on historic averages, that could mean a drop from 33% to 28% upgrading their phone each year, or a lengthening of the average cycle from around three years to closer to four years.

That’s a subtle shift, but still an important one – those few percentage points translate into millions of phones not sold this year that would have been sold last year. As long as the smartphone base continues to grow, the slowing upgrade rate is offset somewhat by new customers coming into the market, but the former effect is going to outweigh the latter going forward.

A Different Approach to Upgrade Cycles

The worry here is this isn’t just about a change in the way people buy phones in one market – the US. It happens to coincide with that trend in the US but there’s actually something else going on here as well. In the past, two-year smartphone upgrades were not just driven by the carriers’ approach to contracts but by strong consumer preference to regularly replace their phones. Major device makers have always ensured the two-year cycle looked attractive to consumers, with Apple in particular making cosmetic external changes on that basis for most of the history of the iPhone. But what happens if consumers stop thinking in those terms? What if, instead of upgrading every two years by default, they make a conscious decision each year to evaluate that year’s new hardware and decide to skip some versions? What if they skip two?

Now, some people have obviously always done exactly this – we all know someone who’s still carrying around a four or five-year-old smartphone and sees no reason to upgrade. They’re the reason why reported upgrade cycles have already hovered around three years rather than two – these are averages after all and, for every person who upgrades their phone annually, there are others who keep them for half a decade. The difference now is that even those who went with the default two year option previously are starting to change their behavior.

The example of Samsung’s Galaxy S6 last year is a great starting point for thinking about this. The hardware was significantly redesigned, with more metal and glass and less plastic, and the specs were also given a nice bump. But figures suggest many would-be upgraders simply passed on that device and decided to hang onto their S4 for another year. This year, Samsung continued with much the same hardware design, but is seeing better sales in the early running. What made the difference? Small tweaks like restoring external storage and waterproofing convinced people who took a pass last year to upgrade this year instead. People didn’t want to give up those features and were content to keep the older device they had and wait another year.

Consider the iPhone SE, Apple’s first premium 4-inch phone in two and a half years. Yes, Apple still sold 30 million 4-inch phones last year, but how many more people just held onto their aging iPhone 4, 5, or 5s? Just as some people seem content to forgo short-term personal relationships while waiting for Mr or Miss Right to come along, so some smartphone users are now happy to wait for the right device to come along. The iPhone SE takes advantage of this trend by tapping into specific unmet needs during a time when many have put their upgrades on hold.

Broad Implications for Phone Makers

The downside, though, is in the context of annual smartphone release cycles, misfiring just once could now be more costly than ever for phone makers. Leave out a feature many people rely on or simply fail to provide a really compelling new feature for people to hanker after, and you could miss out on an entire year’s worth of upgrades. Whereas the two-year cycle could be counted on to drive decent upgrades almost regardless of the hardware in the past, each new release now has to justify those upgrades much more. This puts lots of pressure on, for example, Apple’s next iPhone this fall and its ability to drive another big upgrade cycle. Tim Cook keeps reporting record numbers of Android switchers, but we’ve heard little recently about upgrade rates. Back in January, some 60% of the pre-iPhone 6 base still hadn’t bought one of the new handsets (we didn’t get an update on this stat in April). What if that pattern of behavior continues or worsens with a hypothetical iPhone 7?

Beyond Apple, smartphone makers in general are going to have to start thinking in new terms about smartphone upgrade cycles and what those look like going forward. On the one hand, it means doing whatever they can to make the two-year upgrade as attractive as possible, with significant performance improvements and new features. But it also likely means adjusting to the reality that the average cycle is going to continue to lengthen, which has dramatic implications in an increasingly saturated global premium smartphone market.

I don’t know about other markets, but in North America, there was no advantage to not upgrade when your two year contract expired — because your monthly cost did not go down at the end of the contract period, you were leaving a free device on the table if you just kept your old phone. And switching from a contract plan to a prepaid plan at the end of the contract period involved several downsides (like roaming charges) that made staying with the contract plan more desirable and simple.

Now that the phone is paid for with a separate monthly charge, there’s no incentive to upgrade when the phone is paid off. So I’m completely unsurprised that people are keeping their phones for longer.

Funny, I got energetically shot down when I made that remark about 2 years ago ^^

Another dimension to the issue: not time, but price. Once people realize they’re happy with a 3-4yo flagship, aren’t they bound to realize when time does come to refresh their device that a 1yo flagship would already be a huge upgrade, and probably makes more sense than paying top dollar for the absolute latest gadget ? In the Android market, 1yo flagships are about 50% cheaper than at launch (LG’s G5 is currently 700€, last year’s G4 is 380€ + frequent sales; Samsung’s Galaxy S6 didn’t go down as sharply in list price, but sales are even more frequent and drastic). This year’s flagships aren’t 2x better than last year’s on any axis (performance, picture quality, battery life, transfer speeds…) except maybe social value (and that’s if your peer group value “latest” over “wise”).

Apple does have slower depreciation (-$100 vs -50% ?) so maybe the issue isn’t as stark on that side of the fence.

I’m wondering how a market can be both commoditized because undifferentiated products (which is often said here about Android) *and* sensitive to a single OEM’s product misses. I’d expect buyers to have switched away for Samsung, not to have waited for it to fix it product lineup ? Or is there brand loyalty in Android too, in the end ?

Last year’s GS6 was weak, so I told people to get an LG G4, which a) wasn’t as compromised as the GS6 and b) was conceptually close to previous Galaxies (function over form, SD & removable battery, plasticky unless you shelled out for the leather back…).

Last year did have an ecosystem-wide event, with Qualcomm’s 810 a huge miss, in practice not improving over 2014’s 805. The rest of the components (camera, RAM, Flash, touchID…) did forge ahead.

Also wondering if Android’s updates issue isn’t, in that context, an advantage: being stuck on a 2yo Android version doesn’t matter because it’s built into the ecosystem (apps run, new features ie Pay, Wear, Fit, Car… are backwards compatible and OS apps and tools are upgraded anyway via the app store), but 3+ years does start to sting, probably priming for an upgrade.

Then again, 1st-tier phones are updated at least once, so they don’t hit the 3yr-old OS issue until after 4 years, by which time even flagships are showing their age (Samsung Galaxy S3 and Note 2). And non-1st-tier buyers probably don’t care to start with, plus the device will fall apart around that time anyway.

Good enough.

My iPhone 5 was good enough.

Now, finally, the iPhone SE is compelling because I want small AND Apple Pay.

To be more specific, carriers charged about $20 more per month for their monthly service, about $40 per line. Baked into that was $20 for phone subsidies that supported the $200 to $300 for a new phone every 2 years.

Now, thanks to T-Mobile, the carriers break out the phone cost, charging just $20 per line. So we’ve gone from a situation when it made economic folly not to upgrade, because we were paying regardless, to just the opposite.

Indeed. They still subsidize in Canada, so my brother is both taunting me with his “free” flagships, and moaning about his $CAD 80-ish mobile bills. I get to flaunt my $20 contract (that also includes my yearly Canada jaunt) but my 2yo midranger… not so much ^^

($80-$20) * 24 = 1,440, so I *could* get a couple flagships with the contract savings, but the visibility of that price is a huge deterrent. I got lots of better uses for $1,100. (looks at his 3 tablets). I mean… different… uses ;-p

Unrelated tidbit on how unreliable user satisfaction surveys are: http://arstechnica.com/science/2016/05/user-ratings-are-unreliable-and-we-fail-to-account-for-that/ .

“user ratings seem to be heavily influenced by subjective factors like brand image. Premium brands and more expensive products had inflated user ratings [compared to Consumer Reports ratings]”

Food for thought.

Actually similar studies have been shown regarding Consumer Reports reader surveys. For instance people think Honda’s are more reliable so buying a Honda is supposed to be smart. If things go wrong, some people either under report it or don’t say anything because it would signal they were wrong. As opposed to US brands that are supposed to break down people are more likely to report them and get upset about them than Hondas. When actual repair records are compared there is usually little difference.

Joe

eta: Premium brands are not as immune. Jaguar had a terrible reputation for a long while. Then all of a sudden satisfaction ratings improved. When repair records were examined there was little change. But how jaguar handled the issues is what improved.

All of this is from my days as tech support for an auto consultant.

JF

Indeed, but that does drive home 3 things:

1- data is better than opinion. I’m often amused at the difference in French vs US reviews, because US reviews don’t seem to strive for any kind of objectivity. French Les Numériques evaluates smartphones’ screens by measuring contrast, deltaE, color temp, brightness, uniformity, reflectance, latency, and touch input lag. Most US sites barely do 2 of those. Not that the gut feeling is useless, the quantified nitpicking can miss the big picture or anything not quantified.

2- Perception is both worthless and everything. People can be utterly convinced of the wrong thing, yet if you’re convinced your breaks-down-thrice-a-year car is premium, well, you paid the premium for it, that’s the goal, who cares about reality when the money’s in ?

3- Data has to be observed, not declared. Questionnaires can only gather what people feel about something, not actual events/situations.

I agree with all that. The only problem with #1 and #3, there is still a subjective choice made as to which data is important to measure and why. That’s why there is no such thing as “objective”. We may have data, but it is always subjective regarding what to measure, why, and the interpretation (perception) of the data. There is never _just_ the data. All those data points in #1 are certainly measurable. That doesn’t automatically make them the most important things to consider.

Joe

Both my statistics and my marketing teachers insisted you should validate what you measure, how, and anticipate issues/correlations/causations with experts. Everyone’s got blind spots, but several informed+diverse points of view should cover all angles.

What’s more pernicious is the practicality of it all. Observing is hugely more expensive than surveying. And even surveying is hard to do right. I jump at the chance to do surveys either IRL on or the web, I’m usually… not impressed. There’s often a huge selection issue, then questionnaire bias, then interviewer bias, then interviewee bias when the urge to get out of this rises… ^^

Or you can DIY some in-depth stuff, but then it’s hard to rise above anecdote. I still try that though, at my scale it’s the best I can do.

But all this is what makes it interesting to me. A group of people agree on a set of values that are used to determine what is (and maybe what isn’t, too) worth measuring (Foucault!). But that’s what leads to discoveries—when someone comes along with a different set of values to assess old data and find new data.

And then the whole observer effect! There is always a context to the data.

That’s also why I find AI so intriguing (and Bob’s article on it, too). In order to teach AI to learn we have learned so much about how we learn and know, what we value when looking at a bunch of “data” to pick out the relevant pattern.

That’s also why I like this website most. I think Ben and company do the best job of contextualizing the data, seeing it within the cultural framework of origin. There is always a story in which the data resides.

Joe

Agreed. But the high-level view is also dependent on the lower level. For example (cf Ars article), reported Customer Satisfaction is what surveyees want to tell us about what they think their satisfaction is. There’s 2 degrees of corruption to the data: 1- It’s not what they think it is, but what they want us to think they think it is and 2- it’s not what it is, but what they think it is.

Any reasoning built on that data prima facie is iffy.

That issue can be tempered by a) looking at time series (assuming the various corruptions stay mostly stable) so for changes, not levels, or b) looking at other groups (again, assuming corruption is the same across groups, which is at least as iffy as assuming it stays the same over time, cf your example of Consumer Reports readers vs general public) so for deltas, not levels.

Some level of subjectivity (or corruption) should always be assumed, both from the suppliers of the data and the ones assessing the data. It’s human nature. At least on sites like Amazon I have a chance actually infer the perception. Unlike a CR survey where I only get their tabulated results, or their assessment of hanging chads.

It’s a tough act. We need some level of subjectivity. We want to hear from actual people with actual experience, those both in the data and collecting the data. At the same time, if one works within a certain framework regularly results at some point are likely to be somewhat predictable. Then we want someone who can bring some different thinking, different values, different language to see or find new things.

I don’t have a problem with anecdotal data. It is still data. And in some regards more reliable because there is usually direct interaction with the data, more capacity to ascertain viability. Sometimes nothing beats being able to look someone in the eye as they tell you about something. People usually assign “anecdotal” in an effort to undermine the perspective. More a power play, similar to when someone in a debate tries to throw the “semantics” flag.

But, then, it is always a matter of perspective.

Joe

Still using iPhone 5 here. See no reason to upgrade.

I can’t even think of what feature a new phone would need to have to make me upgrade.

Phasers? I’d upgrade for a phaser feature.

But seriously… um… Built in HD projector? That’s all I can think of.

The market is maturing, slowing down. All of the obvious territory has been mined, and the upgrades are more incremental.

The biggest upgrades Apple could make to the iPhone at this point are longer battery life, a better camera and better speakers.

Things like force touch (admittedly something I haven’t tried yet because I’m still on an iPhone 6 and don’t know anyone with a 6s) seem more like complications than advancements to me.

Thank you for great information. I look forward to the continuation.

But wanna say that this really is quite helpful Thanks for taking your time to write this.

We are a group of volunteers and starting a new scheme in our community.

Your website offered us with valuable info to work on. You’ve

done an impressive job and our whole community will be grateful to

you.