The digital download, ushered in to the mass market more than a decade ago by Apple’s iTunes music store, is in rapid decline as people shift to streaming services such as Spotify and Apple Music.

The shift from downloads to streaming is highlighted by the biggest-selling singles of this year and 2006, when Gnarls Barkley’s Crazy became the first download-only song to top the UK charts, in a sign the digital format was eclipsing CD sales. Crazy shifted nearly 661,000 units during its nine weeks at UK No 1 and went on to sell more than 1m downloads.

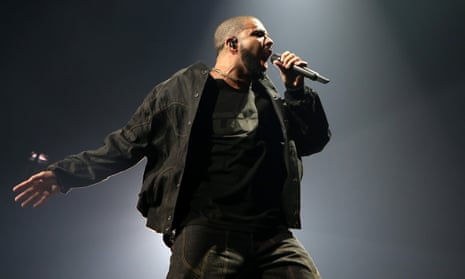

This summer, Drake’s One Dance matched the record achieved by Wet Wet Wet’s Love Is All Around for 15 weeks at No 1 in the UK singles chart – which now combines download, physical and streaming equivalent sales. By the end of September, it had racked up 1.695m sales, including nearly 505,000 downloads and a whopping 119m streams.

Streaming’s advantages are that you can listen to any of millions of tracks whenever you like, and create playlists; paying subscribers can also download individual tracks for offline listening. The disadvantage: if you stop paying the monthly stipend of about £10, the access, playlists and downloads evaporate.

By contrast, a purchased download lasts forever – but it’s the only thing you can listen to.

The people who embraced downloading, started in 2003 by Apple’s iTunes music store, were the tech-savvy types who shifted easily over to streaming. Thus the download is in rapid decline – so much so that at the end of November, the value of sales in the old vinyl format surpassed those of digital in the UK over a week, by £2.4m to £2.1m. At about £20 an album, vinyl sold about 120,000 units, against the equivalent of 2.6m digital tracks costing 79p.

But look more closely and the gap isn’t that big: at 10 songs per album, digital downloads were only the equivalent of 260,000 albums.

So how much longer do downloads have? A few years and they’re dead, says Mark Mulligan, music analyst at Midia Consulting: “It’s going to die before the CD. The CD has a fairly universal player, where there’s always at least one in a house. And the people who grew up buying CDs are the older music consumers – the CD will literally die out only when they do.”

Downloads outsold physical formats for the first time in the UK in 2011, when streaming services were in their infancy. But even by 2014 they were falling, from £397.3m the previous year to £338.1m, while streaming grew to £175m. That trend is continuing.

Apple still controls the digital download market, with about 65% to 70% of the total, says Mulligan: he suggests that the death knell for downloads will come with a redesign of the iTunes app interface that de-emphasises downloads in favour of the Music subscription streaming service. “Last year downloads declined by 16% in nominal terms,” he says. “This year they are tracking to decline by between 25% and 30%.”

By 2019 the business could be worth just $600m (£485m) globally, compared with a high of $3.9bn in 2012; by 2020, Apple might decide that the download business isn’t worth troubling with, and make the iTunes store effectively invisible, Mulligan suggests. “The narrative of services-based music would be complete.”

Apple, however, resists the suggestion that it’s about to turn off the download tap. “There’s no end date … our music iTunes business is doing very well,” Eddy Cue, Apple’s senior vice-president of internet software and services, told Billboard magazine in June, on the first anniversary of the Music subscription service. “Downloads weren’t growing, and certainly are not going to grow again, but it’s not declining anywhere near as fast as any of them [in record labels] predicted. There are a lot of people who download music and are happy with it and they’re not moving towards subscriptions.”

Cue recently said that 60% of people using Apple Music had not bought content from the iTunes music store in the past 12 months, suggesting they were either “lapsed” downloaders, or never were. That makes their monthly revenues all gravy for the music industry, he said.

Certainly the good news for labels and musicians is that the streaming services are attracting growing numbers of subscribers, paying monthly fees of up to £10: Spotify has 40 million, and Apple recently said it has passed 20 million. Smaller services such as Deezer and Tidal have a few million between them.

However, the music industry, which has fretted that each shift in music format since 1995, from MP3 piracy to downloads to streaming, is driving down revenues, is now so worried about the effect of YouTube on streaming revenues that the US labels tried to push streaming payments on to the agenda of Donald Trump’s “tech summit” in mid-December, when representatives of Apple, Google, Microsoft and others met the US president-elect.

What the RIAA, which represents US labels, was complaining about is known in the industry as the “value gap” – the difference in effective per-play payments between audio services such as Spotify, and YouTube.

YouTube, though, remains the world’s biggest venue for music streaming, with millions of videos that can be combined into playlists. Hook your phone or computer up to a speaker, and it’s just like Spotify: you’ll get the music, and the audio from any video ads, and then can pick and choose from a huge catalogue.

Though the latest figures only cover the first half of 2015, the monitoring service Nielsen reckons that YouTube delivered 60% more music streams than all the on-demand music streaming services combined – and that the gap had grown since the same period in 2014. The arrival of Apple Music in June 2015 might shift that, but it’s unlikely.

What riles the music business is that the amount that YouTube pays it per track played works out as substantially less than Spotify or Apple Music.

Whereas the latter two services have complex agreements with the record labels setting a per-play fee, YouTube pays out a share of the ad revenue that any track identified as belonging to a company earns. That tends to be lower than a per-track fee, because advertising prices and value varies enormously. Mulligan says: “Video consumption went through the roof in 2015, but there weren’t enough ads to put against it – so the ad revenues paid grew more slowly than consumption.”

Hence the RIAA’s push to get streaming payments on to Trump’s mind at the tech summit. It’s unclear whether it succeeded.

YouTube says the ad-funded model has transformed the music video from a costly promotional tool into a new source of revenue. “In the last 12 months, we’ve paid out $1bn to the music industry in ad revenues alone, and are working collaboratively with them to bring more money to artists,” it says.

This doesn’t sit comfortably with the music industry. David Price, director of insight at the IFPI, the global trade body for the recording industry, says: “We don’t believe YouTube is properly rewarding artists for the huge consumption that’s going on there. But in the last year we have seen the EU take positive steps towards creating a better and fairer licensing environment in Europe.” The BPI, the UK music industry’s trade body, complained in May that artists earn less from YouTube than they do from vinyl.

But in the long run, streaming is the only game in town – along, perhaps, with the CD and vinyl. The download once looked like the future; now, the question is how much more of a future it has.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion