The smartphone-vs-DSLR shootout has become something of a tradition here at the Ars Orbiting HQ. We did one in 2014 and another in 2015, relying on my own (small) skills as a photographer to stage and shoot a bunch of different images using both the latest model iPhone and my Canon 5D Mark III DSLR.

For the past two years, we’ve had essentially the same two takeaways: first, that smartphones take pretty solid pictures when the lighting is good; second, I am a crap photographer and we need to hire someone who knows how to compose a scene if we’re going to keep doing these.

Well, good news, everyone: this time around, for this shootout, we got together with Houston-area pro photographer Jay Lee. This partnership has resulted in some excellent images without any of the casual mistakes my shots exhibited in past comparisons. (If Jay’s name sounds familiar, it’s because he gained some Internet fame a few years ago when Slashdot featured his efforts to fight a paranoid conspiracy theorist illegally using his photos.)

We also tried hard to find interesting environments to shoot and wound up at some neat places—inside NASA’s Apollo mission control center, deep underground in a forgotten cistern, and behind the scenes at a local network TV station control room. The idea was to gather shots in several distinct environments: very low light, normal low indoor light, and bright outdoor sun. We also constructed a few shots specifically to show off the iPhone 7 Plus’ dual-camera “zoom” feature, along with its software-based background blur bokeh function.

A note on goals

The idea, as with past tests, was to shoot the same scenes with both a smartphone and a DSLR and then compare the quality of the output. As with all past tests, the DSLRs tend to come out on top—but the thing we’re really looking at is how close the smartphone comes to equaling the DSLR. And, as with past tests, there are a number of areas where the smartphone looks pretty damn good.

Nobody—except possibly Apple’s marketing department—claims that smartphones are better than DSLRs. However, phones long ago left “good enough” territory; images produced by a modern smartphone like the iPhone 7 Plus or Google Pixel can be flat-out excellent when the images are constructed to play to the smartphones’ strengths. Conversely, throwing money at a DSLR and lenses and speedlights won’t automatically mean you produce amazing images—the picture-taker’s ability to compose the shot is still overwhelmingly important.

The gear

For this roundup, we went with Apple’s iPhone 7 Plus as our representative smartphone and a pair of Sony Alpha bodies (an A7S and an A99V) for our DSLR exemplars.

“But Lee,” you ask, “why an iPhone 7 Plus instead of a Google Pixel phone? The Pixel has the best smartphone camera on the planet!”

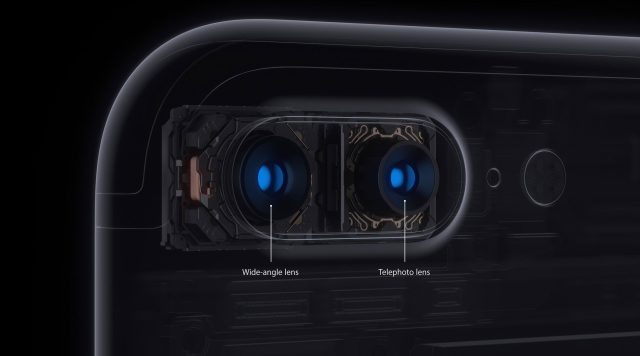

Great question! The iPhone 7 Plus was our first pick for this particular piece because of two things. First, its fancy double-camera arrangement, which includes both a “standard” lens and sensor and a second “telephoto” lens and sensor. The “telephoto” lens and sensor give the phone an advantage over other smartphones when shooting zoomed images, since most other smartphones use digital zoom instead of optical.

Second, because it does something interesting with its two cameras in an attempt to mimic DSLR results. Both images can be combined in software to produce a portrait-style image—a sharp foreground and a pleasingly blurred background. This kind of image is easy to produce on a standalone interchangeable lens-type camera, where you can compose a shot with a shallow depth of field, but considerably more difficult to do with a smartphone. Apple’s solution uses software to fake the blur, and we wanted to see exactly how well it works (spoiler: it’s alright but noticeably less good than the real thing).

Still, the Pixel's camera looks intriguing, and now that the Pixel is widely available—which it wasn't when we took these shots a few months back—we will include it in our next roundup, coming in the first half of 2017.

For each of the shoots below, we tried to match the composition as closely as we could between the iPhone and the DSLR. I had Jay shoot in RAW on all devices and asked him to post-process all the images—iPhone and DSLR both—as he would if he were going to use the photos professionally. The gallery thumbnails below have been further resized and scaled for Web display, but the original full-size images are available if you click through each image. (For reference, Jay used DxO OpticsPro for post-processing—I am also a fan of DxO and have been using it instead of Lightroom for about a year now.)

Scenario 1: Very low light

Our first shoot took us to Houston’s Buffalo Bayou Park Cistern, an abandoned underground drinking water reservoir near downtown Houston that has been renovated and repurposed as a quiet tourist destination. Visitors enter the cistern through a newly constructed public entrance that meanders a bit to give eyes a chance to adjust from sunlight to dimness; the path opens onto a narrow, inclined ledge that rings the chamber.

The cistern is fully enclosed and dark, with light coming from red exit signs and dim orange overhead bulbs. The ledge that circles the space has been reinforced and made safe for the public, but it’s still a fascinatingly creepy vault. Concrete columns rise through the center of the space that was once filled with water; sounds echo for almost thirty seconds. A few people murmuring produces an oddly unsettling aural effect, as if a vast multitude was conversing just behind the rough concrete walls.

-

iPhone 7 Plus back camera (3.99mm, f/1.8), 1/15 second at f/2.8, ISO 1600. The dimness of the cistern proved difficult for the iPhone to deal with, and we had some trouble setting up a timer shot with the RAW app we were using.

-

iPhone 7 Plus back camera (3.99mm, f/1.8), 1/4 second at f/1.8, ISO 1250. Forcing a longer exposure helped a bit, but the iPhone is clearly not meant for this dark of an environment.

-

Sony SLT-A99V with 16-35mm F2.8 ZA SSM lens @ 30mm, 30 seconds at f/3.5, ISO 100. The A99V fared much better, since we could easily set up a long exposure shot for it to drink in all the available light.

-

iPhone 7 Plus back camera (3.99mm, f/1.8), 1/15 second at f/1.8, ISO 1600. The phone tries its best, but without a 3rd-party app to allow long exposures, this isn't the right place to use an iPhone.

-

Sony SLT-A99V with 16-35mm F2.8 ZA SSM lens @ 22mm, 30 seconds at f/3.5, ISO 100. The A99V DSLR, on the other hand, is happy in low light.

Scenario 2: Normal indoor light

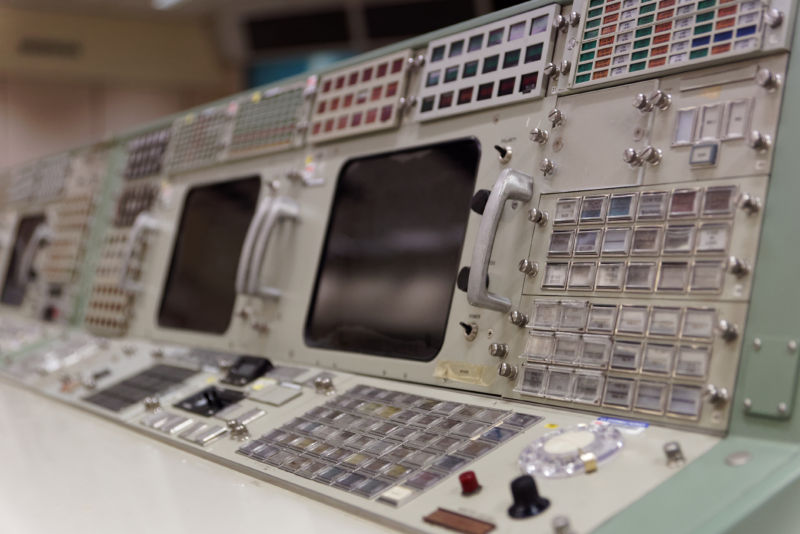

We could shoot indoors anywhere, but with the Johnson Space Center just a few minutes away, why not feature someplace worth seeing? JSC’s Public Affairs Office was happy to let us use the restored Apollo Mission Operations Control Room #2 (MOCR 2) on the third floor of Building 30 to take some indoor shots.

This wasn’t our first time in MOCR 2—we've written extensively about Apollo Mission Control in this piece a few years ago, where Apollo flight controller Sy Liebergot gave us the skinny on exactly how Mission Control functioned and what each flight controller’s console was used for. The room was then, and remains now, almost a holy place, quiet as a church, and the carpeted raised-floor tiles bear the coffee stains of five decades of human space flight. The sage green Ford Philco consoles are vividly iconic, looking simultaneously futuristic and almost laughably antiquated.

Most of the consoles at this point sport a mix of Shuttle- and Apollo-era control panels, and none are in an original flight configuration (which varied from mission to mission anyway). Still, the knobs and buttons proved as irresistible as ever; while Jay tirelessly set up and shot pictures, I chatted with our PAO representative and idly toggled switches on and off. The buttons are heavy and chunky, requiring several pounds of pressure to depress, and they all make the same metallic “CHUNK” when engaged.

-

iPhone 7 Plus back camera (3.99mm, f/1.8), 1/20 sec at f/1.8, ISO 200. Standing at the rear corner of MOCR2. It's dim, but not overly so; the iPhone picks up the room without problems.

-

Sony ILCE-7S with 24-70mm F2.8 ZA SSM @ 24mm, 1/160 sec at f/2.8, ISO 4000. Shooting at f/2.8 to trade some aperture for shutter speed, the background is a bit behind the focal plane.

-

iPhone 7 Plus back camera (3.99mm, f/1.8), 1/13 sec at f/1.8, ISO 100. A close-up of CONTROL, one of the Lunar Module-specific stations. The tiny iPhone lens doesn't really do a depth-of-field blur, so the background remains in focus.

-

Sony ILCE-7S with 24-70mm F2.8 ZA SSM @ 50mm, 1/160 sec at f/2.8, ISO 5000. A similar but very different shot with the DSLR, focusing on the console at f/2.8 and letting the background blur away.

-

iPhone 7 Plus back camera (3.99mm, f/1.8), 1/15 sec at f/1.8, ISO 100. Looking at the Flight Director's console, with the red NASA Bat Phone for a splash of color.

-

Sony ILCE-7S with 24-70mm F2.8 ZA SSM @ 24mm, 1/160 sec at f/2.8, ISO 3200. The DSLR again lets the background blur away, bringing attention to the foreground.

-

iPhone 7 Plus back camera (3.99mm, f/1.8), 1/13 sec at f/1.8, ISO 100. Detail on one of the ABORT panels at the FIDO console.

-

Sony ILCE-7S with 24-70mm F2.8 ZA SSM @ 50mm, 1/160 sec at f/2.8, ISO 2500. When viewed at original size, the DSLR's full-frame sensor clearly captures more data than the iPhone's.

-

iPhone 7 Plus back camera (3.99mm, f/1.8), 1/4 sec at f/1.8, ISO 100. Peeking inside one of the consoles to see some of the guts.

-

Sony ILCE-7S with 24-70mm F2.8 ZA SSM @ 26mm, 1/100 sec at f/2.8, ISO 12800. Pushing the DSLR to ISO 12800 to grab more details.

-

iPhone 7 Plus back camera (3.99mm, f/1.8), 1/25 sec at f/1.8, ISO 40. Standing in the lobby of Building 30, just outside the MCC security doors.

-

Sony ILCE-7S with 24-70mm F2.8 ZA SSM @ 24mm, 1/160 sec at f/4, ISO 1600.

-

iPhone 7 Plus back camera (3.99mm, f/1.8), 1/13 sec at f/1.8, ISO 100. Standing in the front of MOCR2, looking back at the consoles.

-

Sony ILCE-7S with 16mm F2.8 Fisheye, 1/160 sec at f/2.8, ISO 3200. Swapping in a fisheye for a wide shot of the room on the DSLR.

Jay also did some additional indoor comparisons at the Channel 13 studio in Houston, snapping images of the control room and main anchor desk.

-

iPhone 7 Plus back camera (3.99mm, f/1.8), 1/31 sec at f/1.8, ISO 32. The anchor desk at our local ABC affiliate.

-

Sony ILCE-7S with 16-35mm F2.8 ZA SSM @ 16mm, 1/160 sec at f/4, ISO 1600. Plenty of light to work with, so aside from the different framing from the lens, the pictures are pretty close. The DSLR has perhaps a bit less noise.

-

iPhone 7 Plus back camera (3.99mm, f/1.8), 1/8 sec at f/1.8, ISO 80. Though the control room is dim, the iPhone pulls out a solid image (though it's a bit noisy in spots).

-

Sony ILCE-7S with 16-35mm F2.8 ZA SSM @ 35mm, 1/160 sec at f/2.8, ISO 4000. The DSLR copes with the dimness by pushing the ISO.

Scenario 3: Outdoors

The Buffalo Bayou park area of Houston provided excellent fodder for full-sun outdoor shots, with enough visually interesting buildings to make for some good comparisons.

As with most smartphone cameras, the iPhone 7 Plus camera is at its best when it has lots of light to work with. The images produced are indistinguishable at a quick glance from the DSLR images.

-

iPhone 7 Plus back camera (3.99mm, f/1.8), 1/2500 sec at f/1.8, ISO 20. Out in the sun, the iPhone's pix are vibrant.

-

Sony SLT-A99V with 16-35mm F2.8 ZA SSM @ 35mm, 1/160 sec at f/13, ISO 100. The DSLR, of course, also looks great—and benefits from being able to easily control the depth of field.

-

iPhone 7 Plus back camera (3.99mm, f/1.8), 1/3000 sec at f/1.8, ISO 20.

-

Sony SLT-A99V with 16-35mm F2.8 ZA SSM @ 35mm, 1/320 sec at f/8, ISO 100.

-

iPhone 7 Plus back camera (3.99mm, f/1.8), 1/2500 sec at f/1.8, ISO 20.

-

Sony SLT-A99V with 16-35mm F2.8 ZA SSM @ 24mm, 1/160 sec at f/13, ISO 100.

-

iPhone 7 Plus back camera (3.99mm, f/1.8), 1/4000 sec at f/1.8, ISO 20.

-

Sony SLT-A99V with 16-35mm F2.8 ZA SSM @ 18mm, 1/160 sec at f/13, ISO 100.

-

iPhone 7 Plus back camera (3.99mm, f/1.8), 1/3400 sec at f/1.8, ISO 20.

-

Sony SLT-A99V with 16-35mm F2.8 ZA SSM @ 22mm, 1/100 sec at f/11, ISO 100. The DSLR also benefits here with a wider field of view with this lens, presenting the building in a more traditional portrait style.

Scenario 4: Zoom and portrait bokeh

The last set of images compares the zoom and portrait mode functionality of the iPhone with that of a DSLR. The big takeaway here is that the DSLR, with its multitude of lenses and fine control over settings, provides a tremendous amount of flexibility in framing and shooting portraits. Tight manual control over the depth of field coupled with a large lens means you can choose to zoom on objects and still shoot them with a blurred or unblurred background, depending on how you set your F-stop, whereas the iPhone has to use software trickery and produces a much less pleasing blur. The images from iPhone’s zoom lens are also not super great—though they are unquestionably superior to the digital zooms of the past.

-

iPhone 7 Plus back zoom camera (6.6mm, f/2.8), 1/60 sec at f/2.8, ISO 500. This first attempt at a portrait led to a noisy foreground. The background is appropriately blurred, but the image doesn't look that great.

-

Sony ILCE-7S with FE 55mm F1.8 ZA, 1/60 sec at f/1.8, ISO 200. Similar framing on a DSLR shows how it should look, with a sharp foreground and a creamy, even blur in the back.

-

iPhone 7 Plus back zoom camera (6.6mm, f/2.8), 1/53 sec at f/2.8, ISO 80. In a different environment with more light, though, the iPhone steps it up.

-

Sony ILCE-7S with FE 55mm F1.8 ZA, 1/250 sec at f/1.8, ISO 100. The DSLR's picture doesn't look that different.

-

iPhone 7 Plus back zoom camera (6.6mm, f/2.8), 1/54 sec at f/2.8, ISO 80. However, this shot shows the limitations of software-based background blurring. Compare it to the DSLR frame up next.

-

Sony ILCE-7S with FE 55mm F1.8 ZA, 1/160 sec at f/1.8, ISO 100. Beautifully isolated subject and wonderful bokeh in the back.

-

iPhone 7 Plus back zoom camera (6.6mm, f/2.8), 1/60 sec at f/2.8, ISO 50. The iPhone's zoom lens works best when there's plenty of light.

-

Sony ILCE-7S with 16-35mm F2.8 ZA SSM at @ 35mm, 1/160 sec at f/4, ISO 400. But the DSLR still wins on detail and subject isolation.

-

iPhone 7 Plus back zoom camera (6.6mm, f/2.8), 1/60 sec at f/2.8, ISO 100. Away from direct sunlight, the images from the iPhone's zoom lens turn noisy and washed out.

-

Sony ILCE-7S with 16-35mm F2.8 ZA SSM at @ 35mm, 1/160 sec at f/4, ISO 800. The DSLR's full-frame sensor and huge lens scoop up light and detail the iPhone can't get.

The art of good enough

This year’s shootout comes to essentially the same conclusion as the last: a high-end smartphone camera can under many circumstances produce images that are as good as a DSLR’s images. But “many circumstances” doesn’t mean “all the time,” and if you’re going somewhere specifically to take pictures, you’ll still want a high-quality standalone camera.

On the other hand, state-of-the-art smartphone cameras have for years now been good enough to use for basically everything, and the iPhone has the advantage of being on you all the time. The best camera, as they say, is the one you have with you, and an Internet-connected smartphone remains the easiest way for just about anyone to take a picture of a thing and then share that thing with the world.

reader comments

277