Does the internet make you hate?

Commentary: Your colleague isn't a Nazi for voting for Donald Trump. Probably.

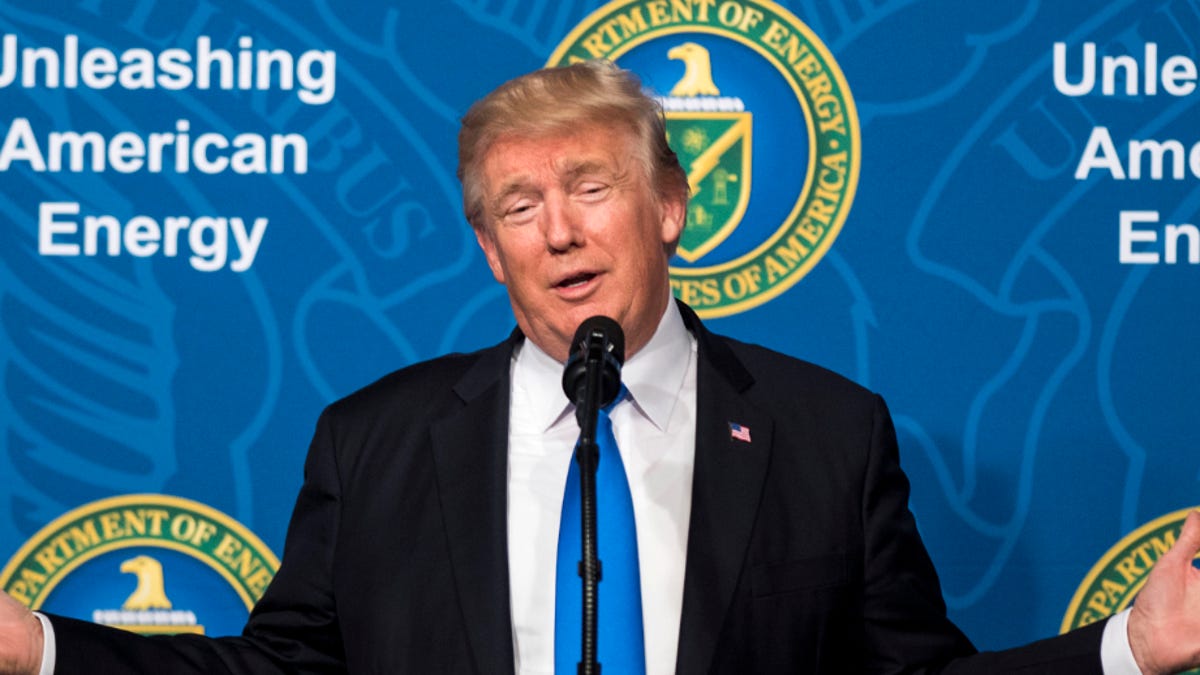

Being on Twitter when Donald Trump was elected was a learning experience. Commentators went berserk, and I started really thinking about the tweets I was seeing.

Tweeters using hashtags like #NotMyPresident and #HateWon implied that anyone who voted for Trump had done so out of prejudice. It's us, the good guys, against them, the bad guys. We hate the bad guys -- and you should too.

The Twitter reaction speaks to a problem I've encountered a lot in recent years. Conversations about important topics don't happen because people classify you as one of the bad guys rather than go through the trouble of engaging with an opposing opinion.

Trump did not win. Hatred won. Racism won. Sexism won. Ignorance won. I will not recognize a bigot as my leader #HesNotMyPresident

— anJEL (@macmotavator) November 9, 2016

Trump didn't win. Racism won. Sexism won. Hate won. Lack of education won.

— ♤! (@nora_muhmd) November 9, 2016

#ElectionNight #StillWithHer #HesNotMyPresident #trumpwins

congratulations America, you just elected hitler the second #electionday #ripamerica #HesNotMyPresident #DonaldTrump

— tay (@1Daficionado) November 9, 2016

I understand why. Every day, the internet exposes us to so much hate it becomes hard to not see it in real life, even if it's not there. That makes it easier than ever to see your neighbor or coworker or a random stranger as one of the bad guys.

Mad world

The internet is rough. Sexism, racism, religious intolerance are always just a click away. You don't have to dig around the edges of the darknet to find it. An anti-Semitic statement is posted to social media like Facebook and Twitter every 83 seconds, according to the World Jewish Congress. The words "slut" and "whore" popped up over 200,000 times over a three-week period on Twitter during a study last year.

You can only see so much of this malice before you start to expect it offline. The phenomenon isn't unique to the internet. People who watch violent TV believe the world is more dangerous than it is. There's even a name for it: It's called Mean World Syndrome.

Watch enough horror movies and you start thinking there's a killer around every corner. See enough evil on the internet and you may start thinking anyone who disagrees with you is doing so out of hate.

Here's an awkward example. Don't hate me for it.

I'm guessing you've heard of the wage gap, the concept that women are paid less men. If your social media echo chamber leans left, like mine does, one of your Facebook friends has probably posted a story like this one, which basically says women are paid less because of sexism.

Now suppose I were to point out that statistics show men work 3.5 more hours per week than women and that could explain part of the pay gap. Imagine the blowback. I'm not denying the gap exists or that sexism is part of it -- just noting the possibility that it's a complicated issue.

It'd be easy for someone to accuse me of sexism if I did that. (I mean, yeah, it is an obnoxious argument to have over Facebook.) And I get why. When our Facebook feed is clogged with stories like a Polish MEP saying women are lazy and less intelligent than men, no one wants to hear an issue is complicated. Saying that, no matter how legitimate, just makes you one of them.

So what happens? Not conversations. The most complex and important issues we face as societies become no-go zones. Amazingly, I've found the wage gap to be a less invidious conversation than others relating to gender, race, religion and politics -- the very things we need to talk about.

Censored ideas

I like talking to people I disagree with (at least, I think I do), but it's becoming an impossible process. That's irritating for me, but poses an actual problem: If there's no mutual understanding, there can be no meaningful changes.

It's not just me, though. Visit a college campus if you want to see how online polarization makes conversations more difficult offline.

Jordan Peterson, a psychology professor at the University of Toronto, is at the center of it. He objected to a bill that would make failing to refer to a transgender person by their preferred pronoun -- like Xie, Xur or more than two dozen others -- hate speech. Peterson doesn't have a problem with non-binary genders but he takes issue with an "attempt to control language… by force."

Naturally, students protested, accusing him of transphobia and demanding a resignation.

"There's no real communicating with people who are demonstrating like that," he said on The Joe Rogan Experience. "They're not looking at you as if you're a human being. You're the realisation of their conceptualisations."

In other words, the problem isn't what he said. It's what people believe he said.

There are plenty more examples where opposing opinions are classified as hateful rather than actually engaged with. Ben Shapiro, a conservative US commentator, questioned the need for safe spaces -- rooms in colleges designed to shield students from hate speech -- but found himself at the center of protests at the University of Wisconsin, where students thought his argument was itself hate speech.

Christina Hoff Sommers is a scholar who dissects what she calls "feminist myths," and it's not hard to predict how that goes down on campus. Late last month, Evergreen State College biology professor Bret Weinstein opposed a student initiative that asked all white students to stay off campus for a day, which some students saw as an act of bigotry, leading to chaotic rallies and the need for riot police on campus.

Riot police.

My social media circles lean left, but I'd bet similar things happen across conservative circles. The internet exposes conservatives to the most extreme positions and overreactions of the left, and instead of "bigot" or "sexist," the right pejoratively uses terms like "social justice warrior" or "feminist" to dismiss arguments and issues.

For all that's said about the internet as a communication tool, it can make real-word communication much harder.

It's true. There are a lot of bad guys out there. But at least verify a person is worth hating before you hate them.

Tech Enabled: CNET chronicles tech's role in providing new kinds of accessibility.

Technically Literate: Original works of short fiction with unique perspectives on tech, exclusively on CNET.