Back in September 2014, Ars Technica's Andrew Cunningham took on a Herculean challenge in modern computing. Egged on by his coworkers, he used a PowerBook G4 running OS 9.2.2 as his "daily driver" for a couple of days, placing a turn-of-the-century bit of hardware into the present tense. It's no surprise that almost nothing was achieved that week (except for, of course, the excellent article).

Years later, I had that story on my mind when I was browsing a local online classifieds site and stumbled across a gem: a Macintosh IIsi. Even better, the old computer was for sale along with the elusive but much-desired Portrait Display, a must-have for the desktop publishing industry of its time. I bought it the very next day.

It took me several days just to get the machine to boot at all, but I kept thinking back to that article. Could I do any better? With much less? Am I that arrogant? Am I a masochist?

Cuppertino retro-curiosity ultimately won out: I decided to enroll the Macintosh IIsi as my main computing system for a while. A 1990 bit of gear would now go through the 2018 paces. Just how far can 20MHz of raw processing power take you in the 21st century?

The bad news (that's not really bad at all)

It's important to state this from the outset: the IIsi, or any other vintage computer, is generally not suitable for home or office use in modern times. And after doing it, I won't be advocating for the experience to others.

But, what is “suitable” anyway? A vintage car enthusiast is probably not going to recommend many of their motors for getting from A to B, yet these older cars can still fulfill their primary role as a means of transportation—just not as quickly, or as reliably, or as safely, or with air conditioning.

An optimist may start to see these technical limitations as opportunities, the flaws as charming characteristics, the dubious reliability as a challenge to surmount. The wheels may turn a little slower, and the entire cabin might start to shake when traveling at highway speed, but it sure is fun. Without wanting to sound like a contrived car commercial—it's not about the destination, it's about the journey. The same goes for some dedicated tinkering and a bit of old tech.

When I first flicked the power switch on the Macintosh IIsi, it didn't work at all. Replacing a suspect capacitor inside the power supply resulted in a small explosion and venting of the “magic smoke”—clearly, this wouldn't be a simple fix. For a time, the IIsi simply looked as if it was on life support, with a half-hacked up ATX power supply being used to deliver the required voltages to the logic board.

I also had issues early and often with sound reproduction, which may be due to failing capacitors on the logic board itself. These tin cans often wreak chemical havoc across the logic board when they start leaking, but they too can be replaced.

I started by popping in a new battery, used to maintain the PRAM (Parameter RAM), meaning that I don't have to reset the clock and other settings every time I boot up. Naturally, as soon as things seemed to be going well, the hard drive died—not an uncommon occurrence.

Thankfully, everything else that came with the IIsi worked great from day one, needing no repairs whatsoever. To extend the classic car metaphor just a little further, it only took a little elbow grease before I was ready to road-test the IIsi. The machine could take me from A to B, moving at just a fraction of the speed that I'm used to. I knew immediately from the first successful boot up: despite the obvious shortcomings (or perhaps due to them), this would be an enjoyable journey.

-

If you'll indulge us... since we *did* have the Portrait Display, we had to get some portrait-orientation images...Chris Wilkinson

-

When's the last time you've seen one of these, folks?Chris Wilkinson

-

Proofing my copy the way a 1990 publisher would've wanted it...

-

Shoutout to the #arstechnica IRC channel, still kicking.Chris Wilkinson

What we're working with

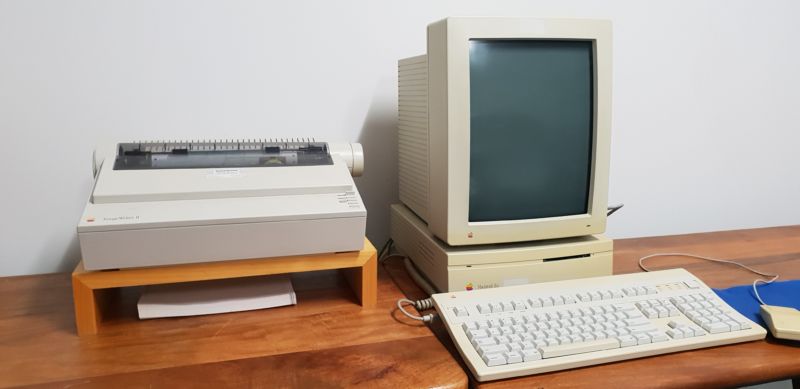

The Macintosh IIsi, released in the third quarter of 1990, comes out of the factory with a Motorola 68030 processor clocked at 20MHz, 5MB of RAM, and an 80MB SCSI hard drive. Similar to its Apple contemporaries, it also came with a 1.44MB floppy disk drive, LocalTalk ports for a printer and modem, and an ADB port for keyboards and mice.

In the passage of time, this particular Macintosh IIsi received a couple of upgrades. Its single expansion port is occupied with a bridge card that converts the PDS slot into a more capable NuBus slot. This bridge card also includes a math coprocessor, which boosts the performance of some tasks.

The NuBus slot is taken up by an Ethernet card for fast networking, and this should connect the IIsi to the Internet with limited fuss. The RAM has been upgraded to17MB (1MB on the logic board, plus 4x4MB SIMMs), and the hard drive has been replaced with a SCSI2SD, a modern SD card solution for mass storage over SCSI.

For the record, the SCSI2SD is the only real “cheat” used in this entire setup, replacing 80MB of spinning platters with 4GB of flash memory. This ridiculous amount of storage would have cost around $36,000 USD back in September 1990. I/O speed is still limited by the SCSI bus, and tests put its performance pretty close to that of a spinning disk.

I used System 7.5.5, although many of the same tasks would have been possible on System 6 and up. System 7.5 included many quality of life improvements, such as the Control Strip and compatibility with a massive variety of extensions and applications, at the expense of RAM and overall system performance.

The Portrait Display supports a resolution of 640x870 pixels, with up to 16 greys (no color here). The monitor was designed with desktop publishers in mind, with a screen ratio and resolution supporting full-page WYSIWYG editing of documents, flyers, posters, etc. This monitor and many like it were quite popular in their day, but these were eventually made obsolete by high-resolution color CRT monitors in the traditional 4:3 ratio. The influence of these portrait monitors can still be seen today on some office desks, with some users opting to use their modern 16:9 LCD screens in a portrait configuration.

For the record, I restricted myself to using the IIsi exclusively in the creation of this very article. From word processing to research to contacting Ars Technica staff, this will be the computer that I will be using. [Editor’s note—Who doesn’t like editing copy from a PDF?]

-

Ars actually started 20 years ago (1998), so has anyone done this before?Chris Wilkinson

-

Hello, old friend.Chris Wilkinson

First impressions

Word processing and spreadsheets ("Yay!" said no one)

Word processing on the Macintosh IIsi is a classic, well-understood experience. Both Microsoft Word 5.1 and ClarisWorks 2.1 perform as you would expect and modern day word processor.

As I pressed on with using the IIsi, I found the experience to be an overall pleasant devolution: no wizards, no updates, very simple user interfaces, no essential updating required. After just a couple of CPU cycles, you land on a blank page to begin your masterpiece. Typing on Apple's renowned Extended Keyboard II also certainly helped.

The full-page capabilities of the Portrait Display are evident here. While it's hard to comprehend these days, working on an entire page of formatted text and graphics, without scrolling or scaling, was remarkable for 1990. Combined with the true-type fonts that scale infinitely, the IIsi becomes a surprisingly capable desktop publishing machine, no matter what year it is.

Spreadsheets are a similar story, with the Portrait Display offering more screen estate for longer documents.

reader comments

359