Writers Have Always Loved Mobile Devices

Writing boxes, popular from the 17th century, provided the same pleasure as today’s laptops and custom word processors: to make the experience of writing pleasurable, whether any actual writing gets done. An Object Lesson.

Writing is a mobile art. People do it on laptops, tablets, and phones. They write—or type—while walking, waiting for a doctor appointment, commuting to work, eating dinner. Although writing’s mobility might seem a product of modern digital gadgetry, there’s nothing new about writing on the move. Digital tools are but the latest take on a long tradition of writing in transit.

Preceding smartphones by centuries, writing boxes were among the first mobile-writing inventions. Small and portable, these wooden boxes were equipped with a flat or sloped surface for writing and an interior space for storing materials like paper, inkwells, quills, pens, seals, and wax. Many also included compartments for storing letters and postcards, and secret drawers with locks for private papers, important documents, trinkets, and valuables.

Writing boxes had an effect a lot like that of today’s electronic devices: They created an aura around writing, investing tools with an energy and power that enabled writers to gain pleasure from writing—or from the idea of writing, which might be equally gratifying.

In 17th- and 18th-century Europe and America, storage boxes of all kinds proliferated: Bible boxes, bridle boxes, voting boxes, keepsake boxes for a baby’s first tooth and lock of hair, and photo boxes, among others. Writing boxes stored physical writing tools as well as ephemeral fruits of writing—traces of literacy, ritual, and memory.

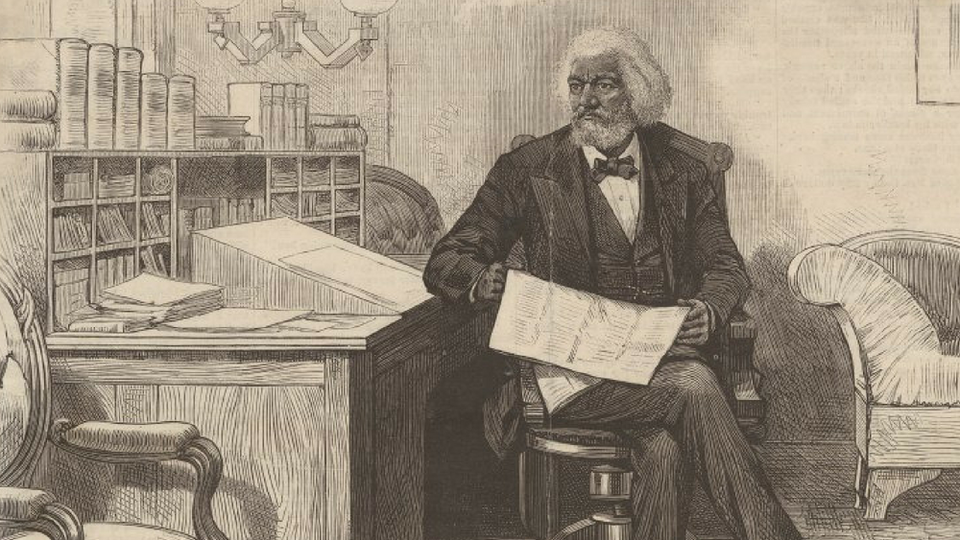

Like laptops today, writing boxes were common tools of working writers. Lord Byron used one, as did Jane Austen, the Brontë sisters, and Charles Dickens. The poet Alexander Pope reportedly insisted that his writing box be placed on his bed before he woke so that he could immediately capture his thoughts in writing before leaving his bed. Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, and Alexander Hamilton all wrote on writing boxes, too. In “The Laptops That Powered the American Revolution,” the historian Bethanee Bemis explains that during the Revolutionary War, Washington’s “most pivotal decisions” were issued from his writing box rather than from the battlefield.

Ordinary people used writing boxes, as well. Expanding literacy rates and the creation of the U.S. Postal Service in 1775 made letter writing more popular, and burgeoning travel among the leisure classes influenced the form and function of writing boxes. Like smartphone cases today, writing boxes were often designed to be gendered accessories. A “lady’s traveling box,” designed by Thomas Sheraton (and believed to be the general template for Austen’s writing box) featured both writing and dressing accessories like brooches, buttons, and sewing kits. Travelers’ writing boxes for young men included space for shaving materials as well as “journals in which they recorded their impressions and some made drawings of historic landmarks and objects.”

Mechanically, writing was still a complicated affair in the 1700s and 1800s. The writing box thus solved a practical problem. People needed a way to carry dip pens, pen nibs, and inkwells, as well as paper, stamps, and envelopes. As practicality led to widespread use, writing boxes became decorative, too. Designed and built by skilled artisans and woodworkers, writing boxes were embellished with high-quality velvet interiors, brass details, leather slopes, engravings, and clever hidden drawers. Writing boxes were personal possessions as much as emblems of social position.

When fountain pens and manual typewriters became widely available in the early-20th century, the need for writing boxes changed yet again. They eventually gave way to writing desks and general household or work desks. The disappearance of writing boxes wasn’t total, however. People sometimes still use lap desks, a modern descendent of writing boxes, and some antique writing boxes continue to circulate. Aside from those housed in museums, collectors and antique stores sell them online. Reproductions, representing an active, if niche, market, are often accompanied by a bottle of ink and a stylus for nostalgia’s sake and pitched as a salve from the fast writing that typewriters and then computers offered. Rather than speed and efficiency, writing boxes promise a slow writing practice characterized by the physical act of handwriting and the use of labor-intensive writing tools. They cast writing as an act of deliberateness and authenticity, values achieved at least partly by means of a writing tool that regulates pace.

Online testimonials about writing boxes make plain the aesthetic, evocative power these objects accord to writers and writing. On an online forum in 2012, one commenter posted, “I have at long last managed to get round to taking some photos of my victorian writing slope. It gives me such immense pleasure to write on it!” Touring the object for viewers, the blogger describes a secret drawer housing a locket, an anniversary card, house deeds, a doctor’s note, and a woman’s driver’s license from 1951.

By purchasing a writing box or reproduction of one, the modern user, like this collector, might reclaim contact with the past and gain writerly authenticity through closeness to another, otherwise distant time. “Every time I move this slope carefully from its resting place near my desk and set it down on a large square of felt in front of me,” writes the forum poster, “I am transported into a nostalgic reverie of more genteel times, even though that nostalgia may be illusory!”

Those sentiments extend to new writing boxes offered for sale to modern users. One reproduction that sells for $90 is described as “filled with all the paraphernalia to write an impressive document.” It is equipped with a brass melting spoon, seals, and a travel burner to melt wax for sealing, not to mention a quill with nibs and inks in assorted colors. The lavish description of ritualistic writing gear is the selling point. That equipment assures authenticity and proximity to the experience of writing. “It makes me want to be a better writer!” one reviewer reports about a contemporary writing box.

Equipped with antiquated writing accessories, housing treasures, and mundanities long abandoned and likely forgotten, antique writing boxes generate joy and aesthetic pleasure around writing. They foster a writerly identity and highlight writing rituals.

Writing boxes might seem like a precious indulgence for today’s writers, clicking or tapping on laptops and tablets. But writing still retains an aura. Many contemporary writers reflect on the setup of their digital devices with the same attentiveness as fans of Victorian writing boxes or their reproductions.

The writer Noel Rappin, for example, describes his preferred mobile-writing setup of an iPad Air 2, Logitech Keys-to-Go keyboard, and Kanex plastic stand. “It’s really small and light. The keyboard is six ounces, and is smaller than the iPad, and about the thickness of a binder cover.” Sounding very similar to his contemporaries waxing nostalgic for writing boxes, Rappin continues, “I like the ergonomics. The Logitech keyboard has surprisingly good key feel for all that it looks like a chicklet keyboard.” No matter their form, writing apparatuses seem to externalize a writer’s intentions and deliberateness while also making clear that surfaces and tools are not beside the point.

Indeed, writing is so entangled with surfaces that creators of mobile-writing apps have designed “distraction free” writing platforms like WriteRoom and ZenWriter, both of which aim to create alternative writing spaces beyond Microsoft Word with minimal bells and whistles. Just write, these apps encourage. Both acknowledge the scene and stuff of writing while seeking to minimize it. Users of ZenWriter can enable the sound of typewriter keystrokes, customize music, and select a “calming” background. Focus apps suggest that you can achieve the arrangement, feel, and evocative power of your preferred writing scene no matter where you are; a room of one’s own is not stationary but mobile.

Some software and hardware makers have leaned into writing as a mobile, pop-up art introduced by writing boxes. Zoho Writer, a word-processing program marketed as suitable for writing on the go, is unabashedly linked to major literary figures and the capriciousness of inspiration: “Maya Angelou wrote in hotel rooms. Sir Walter Scott wrote a famous poem on horseback. Whatever your process, whichever device you prefer, Writer is there when inspiration strikes.” This same idea is materialized in the Freewrite smart typewriter, which promotes itself as a distraction-free, mobile tool aimed at helping writers find their “flow.” (The bearded, bespectacled cartoon man that Freewrite uses as an emblem also shows how modern writing technology still gets gendered.)

Writing never happens in the abstract, but only by means of objects—not to mention identity, sensory experiences, memory, nostalgia, hopes, and more. Mobile-writing devices help make writing intimate. They empower writers to feel a connection with the world via their tools. Mobile devices are especially good at this because they are adaptable, span a range of material and digital forms, and are experienced as uniquely deliberate lifestyle choices. Whether inspired by the sleek slope of an antique writing desk, an off-the-shelf laptop, or a distraction-free mobile app, writers long for an experience of writing that connects the body and mind to the writing apparatus. Often, that feeling is just as enticing as writing itself.

This post appears courtesy of Object Lessons.