Before actually contacting first responders, the Apple Watch will try to give numerous urgent alerts: tapping the wearer on the wrist, sounding of a very loud alarm, and also displaying a visual alert.

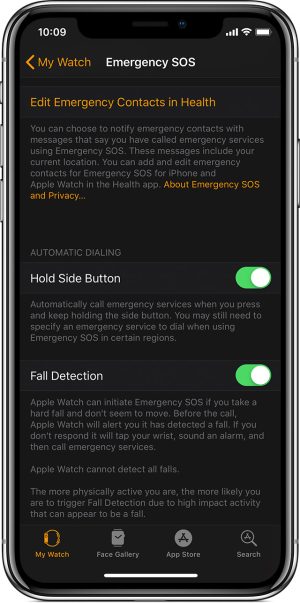

If the Apple Watch detects that the wearer is "immobile for about a minute," it begins a 15-second countdown. After that, the Watch will contact emergency services, which often can use mobile phone data to locate the wearer. (Apple says that the feature is automatically enabled for users who have entered their age into their profile and are over 65.)

The (mostly) opt-in nature of the service may mitigate but not completely assuage concerns raised by some lawyers in the immediate aftermath of the September 12 announcement of the watch.

Elizabeth Joh, a law professor at the University of California, Davis, was quick to point out that, by inviting the police into your home, Apple Watch wearers may be opening themselves up to criminal liability.

Consider: your watch (accidentally) alerts the police to check on you: 4th Amend. community caretaking exception means they can enter your home w/o a warrant. Plain view means they may seize contraband/evidence of a crime. Nice work, guys.

— Elizabeth Joh (@elizabeth_joh) September 12, 2018

In other words, if police are alerted by an Apple Watch of a possible injury, they do not need a warrant to enter a home under the "community caretaking" exception to the Fourth Amendment. This is the notion that law enforcement officers can enter a private space if they reasonably believe that someone needs emergency assistance. It's similar to the "exigent circumstances" exception, which allows police to come in if they believe someone is in imminent danger or physical evidence is being destroyed.

"One of the interesting things here is that, whenever there's a change in the technology, it creates an inadvertent Fourth Amendment question," Joh told Ars. "It's a good example of how design can enhance or detract from privacy in accidental ways. I'm sure there are nothing but very good intentions behind this change in how this Apple Watch is going to work. But there are other considerations as well, because every time there is a change of this sort, there will be accidents, and there will be missteps."

She noted that she would love to hear Apple justify this change in its design.

Apple did not respond to Ars' request for comment on the record, referring us solely to this webpage.

"I would love to hear that cost-benefit analysis," she said.

New York-based criminal-defense attorney Fred Jennings agreed with Joh. He said that he would prefer if the wearer could automatically alert a relative or friend instead of the police.

Exactly. Would much prefer a feature that can automatically dial a user-determined contact.

— fbj.esq.online (@Esquiring) September 12, 2018

On September 12, Jennings explained to Ars by phone that, unfortunately, there have been and still are instances "where people are made less safe by the summoning of police."

However, when Ars sent Jennings the September 20 writeup of the new emergency calling feature, he said his concerns were "confirmed."

"I think 'call auto-detected local emergency services' is a fine and sensible default, but users should have the ability to override that with their own setting," he wrote to Ars. "If I'm in rural Montana, my live-in partner or former-EMT neighbor may be a faster responder than the local police and doesn't come with the same privacy or over-response concerns."

reader comments

237