What is atrial fibrillation, and why has Apple decided that it's worth screening for it? The first question is much easier to answer, so let's get that out of the way.

Your heart has four chambers, two atria and two ventricles. The atria are smaller chambers at the top of the heart, and their contraction fills the larger ventricles with blood. The ventricles then provide the powerful push that sends the blood either to the lungs to pick up oxygen or out to the body once it is oxygenated.

Got no rhythm

The proper coordination of the beating of all these parts requires a carefully synchronized spread of electrical signals through the four chambers. Given the complexity involved in getting this to work, it shouldn't be surprising that it sometimes goes wrong. The fault for problems can be anything from a temporary physical change to a permanent problem with your heart's development that started back when you were an embryo. The consequences can range from irrelevant to fatal.

For example, one common problem is a premature contraction, either triggered by the atria (premature atrial contractions, or PACs) or the ventricles (PVCs). In PACs, the beat will look perfectly normal when its electrical trace is checked—it just happens sooner than the regular rhythm would dictate. Because the beats are normal, PACs don't represent a health threat on their own. They can, however, sometimes be triggered by serious underlying problems, so it's often worth checking them out if they're spotted.

PVCs do result in an altered heart beat, but aren't considered a problem as long as they're sufficiently rare. If several of them occur in rapid succession, they can create serious problems. As such, they should always be checked out.

There are also a number of arrhythmias in which the electrical activity of the heart isn't normal; the most common of these are fibrillations. In this case, the electrical impulses are disorganized and spread through the chambers irregularly. Rather than contracting in a smooth wave, the chambers of the heart spasm and don't generate a solid contraction.

Given that the ventricles power the blood through the body, ventricular fibrillation is fatal. Not much point in screening for that.

Which brings us to atrial fibrillation, or a-fib. To simplify, this is the spasming of the upper chambers, often accompanied by an irregular and often rapid heart rate. While the atria help the heart work properly, the ventricles alone are enough to keep the body supplied with blood. So a-fib doesn't create an immediate health risk. But it poses a variety of long-term ones.

Heightened risk

A-fib has risk because when the atria spasm instead of contracting, blood has an opportunity to pool up within them, outside of the main flow of circulation. Left in the same place for long enough, some of this blood will form small clots that will eventually get pushed out of the heart and into the general circulation. These clots can cause immediate problems, like heart attacks or strokes—a-fib significantly raises the risks of each.

But the small clots can also cause sub-clinical problems, damaging parts of the heart without causing any overt symptoms. In another example, patients with a-fib have a heightened risk of early onset dementia from multiple small clots that weren't substantial enough to trigger stroke symptoms.

Aside from the long-term health risks posed by a-fib, there are a couple of additional things that make Apple's decision to screen for it reasonable. The first is that the problem can be treated in a variety of ways. We have lots of drugs that alter the heart's rhythm, and in some people, these block or limit a-fib. You can also treat the problematic symptom, blood clots, by using blood thinners. Finally, there are surgical procedures that eliminate a-fib entirely in some individuals. A diagnosis can mean protection from the worst of the consequences.

A-fib detection is a challenge simply because there are some people where the arrhythmia is asymptomatic or sporadic. I have experienced both a-fib and PACs, and I can actually feel whenever my heart is out of rhythm and feel the difference between the two arrhythmias. But lots of people can't, and they would never know they were at risk of treatable problems if the arrhythmia weren't picked up during regular screening.

Sporadic and asymptomatic arrhythmias can make monitoring and diagnosis difficult. And diagnosis is important for people who can feel their heart going out of rhythm—they know they have an arrhythmia and don't have to be screened—but don't know what arrhythmia it's shifting into. A diagnosis requires a record of the heart's activity while it is out of rhythm, which can be difficult to arrange when the arrhythmia is sporadic.

Monitoring the arrhythmia is important for people who are using drug treatments, since the drugs can sometimes lose effectiveness, and the patients have no way of knowing. Sporadic onset of the arrhythmia means that it's a matter of chance whether it would show up while monitoring is happening. In my case, I get a sporadic mix of PACs and a-fib, and monitoring helps determine whether I'm experiencing the more dangerous of the two more often.

So there are really two separate issues that the Apple Watch can now address: screening and monitoring.

Screening

Screening is the application where Apple has received FDA clearance, and there's definitely value in that. Effective treatment of a-fib has been shown to reduce the long-term consequences, and those long-term consequences have large costs, both on the patients' quality of life and on the costs of the health care they require. Since there are few known risk factors for a-fib in healthy populations, having it picked up during screening can be a matter of chance.

But the data Apple submitted to the FDA showed there were false positives and negatives. False negatives mean that some people with a-fib won't be detected by the watch. That could be unfortunate for them personally, but it's not going to leave them in any worse shape than they likely would have been before. Hopefully, doctors won't accept the watch's word on things and stop performing additional screening.

The bigger issue could be false positives. Even if these turn out to be very rare, sales estimates indicate that Apple may be shifting roughly 20 million watches a year. At a two percent false positive rate, that could mean over 400,000 people who want to talk to their cardiologists about a-fib next year. There's also the issue of cases where the a-fib is real but inconsequential. We really don't know how often people might experience a brief period of arrhythmia and then remain in normal rhythm for years after. But we do know that a-fib is the most common outcome of what's called "holiday heart" (or sometimes "Friday night heart"), a temporary arrhythmia brought on by excessive drinking in otherwise healthy people.

All of which suggests that mass screening via watch may have good and bad points. It's great for those who have a-fib but are asymptomatic or only suffer it sporadically. Identifying them and getting them treatment will be a positive. But we also may see it identify a lot of patients with false diagnoses, or who have a few extremely rare bursts of arrhythmia. That can affect them emotionally and potentially overburden our cardiac care system.

Monitoring and diagnosis

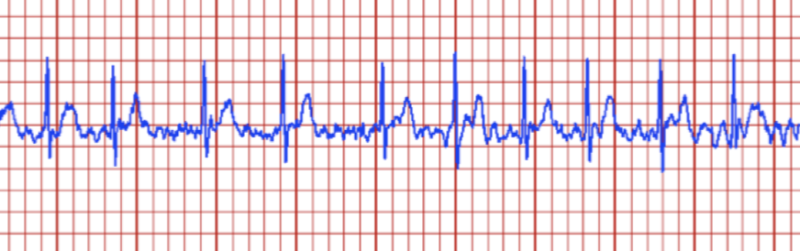

Ironically, it's the applications that Apple hasn't sought clearance for—monitoring and diagnosis—that may make more sensible use cases. Currently, the standard means of handling both of these is the regular use of what's called a Holter monitor, essentially a wearable version of the ECG device. That device generates traces of the heart's activity like the one shown at top, and it has gotten increasingly sophisticated, as it can be applied as a single patch or connected to a cellphone as a Bluetooth device. But Holters have some limitations. If the arrhythmia is sporadic, there's no guarantee that the monitoring will coincide with its appearance. The monitor can also be uncomfortable and tough to sleep with—I've developed an allergy to the electrodes' adhesive, for example.

Because of the erratic nature of my arrhythmias, and because they're symptomatic, both screening and monitoring could potentially benefit from a high-quality personal heart monitor. My arrhythmia only appeared briefly during a week on the Holter monitor, so it was difficult to diagnose until I happened to have an episode while near my doctor's office and walked in for an ECG. A watch could have greatly simplified the process.

For monitoring, my cardiologist and I have shifted to a small Bluetooth device that extracts the heart beat when your fingers are placed on it. Now, instead of hoping I'm on the Holter when arrhythmias hit, whenever I have an instance of arrhythmia, I simply record it and email it to my doctor from my phone. If the watch's ECG function worked equally well, it could easily replace this device for either of these needs.

Because the watch also detects the onset of a-fib, this feature could be easily integrated into the software—throw up an alert suggesting the user take an ECG whenever the system in the background detects possible a-fib. While the quality of a Holter monitor will probably be better, this may not be needed to determine when someone's heart bears closer examination.

For whatever reason, however, Apple has chosen not to go this route, at least at the moment. That decision may be wise. Their first iteration of the hardware and software will be a public health experiment the size of which makes it exceptional. It's probably a good thing to look carefully at the results before pushing further.

Corrections: fixed a typo in the false positive discussion, and elaborated the PVC discussion.

reader comments

114