Loup Ventures went phoneless last week. That is, some of the Loup team turned off our iPhones for a full week and only used Apple Watches for connectivity. It was freeing. And frustrating.

Tech addiction is something we’re spending a lot of time thinking about. We still see solutions and adaptations to tech addiction as huge potential market opportunities. Our phoneless test helped us understand the benefits and pitfalls of addressing addiction through our devices directly.

Before we get into the details of our experience going phoneless, we acknowledge that the Apple Watch isn’t designed to be a standalone device but a companion to an iPhone. To set up a watch, you still have to pair it with an iPhone first. Our experiment stretched the limits of the watch beyond intended use but was still useful to understand how lighter connectivity can benefit us.

This piece will attempt to focus on what we noticed about going phoneless with limited commentary on the watch itself. For thoughts on our Apple Watch experience, we have a separate piece available here.

Core Benefits

Universally, our test group said that they enjoyed having fewer distractions and notifications, which allowed for more time to focus on work or other non-tech related things. The term “freedom” was mentioned often, although directed toward different elements of going phoneless. Some of us felt freedom from the obligation of constant communication (email/text/social), and some of us felt freedom from information (news/YouTube/other video). Some felt freedom from both.

It’s worth noting that I felt this freedom even after significantly reducing apps and notifications on my phone. About three months ago, before going phoneless, I erased all social media except Twitter and eliminated most notifications and badges (red alert bubbles). With those changes, I reduced a lot of reactive time I spent on the device, but still unconsciously check email and messages. I also still fall into watching a bunch of YouTube videos back to back and looking at news curated for me by Google.

In reflection, I think the changes I made to reduce apps and notifications on my phone have done more to shift where I spend my time rather than how much time I spend on my phone overall. It shifted away from social and messaging to YouTube and Google.

Going phoneless actually reduced my screen time. I’d estimate that I checked email/messages about 80% less while phoneless than with my normal notification-less phone. I spent no time on YouTube and very little time reading news. That’s real freedom.

Productivity Matrix

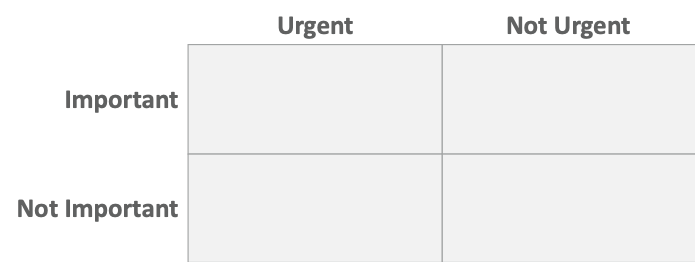

In doing our phoneless experiment, we had an observation about why we felt so much more productive without our phones, and it involves the Eisenhower matrix (thanks Will Thompson for reviving this at Loup). For those unfamiliar, the Eisenhower matrix is a four-quadrant graph with crossing axes of important/not important and urgent/not urgent meant to help people analyze where they’re spending time.

A philosophical observation: To be important, something must possess a relative quality of rarity and significance. If everything were important, nothing would be important in relation to any other thing.

By logical inference, the majority of information we receive must not important. Since our devices inundate us with large quantities of information in the form of messages, notifications, and content, most of that information must be not important.

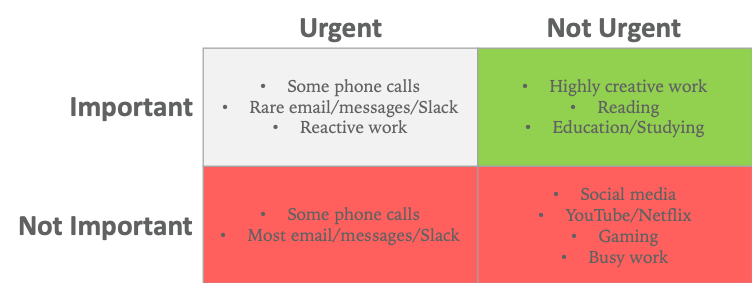

In going phoneless, we eliminated the entire lower half of the graph consisting of not important things. This freed us up to focus on only important tasks. Most…importantly…it freed us to focus more on the important, not urgent category that tends to be the most impactful of the four quadrants.

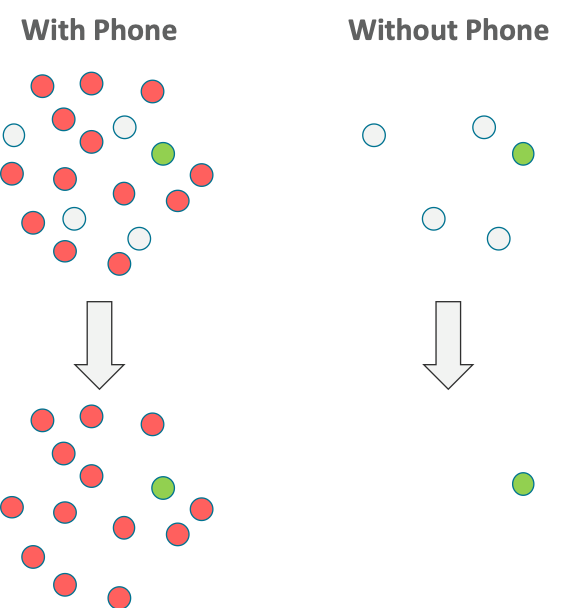

The reason is that the selection set of what to do after you do your important, urgent tasks is significantly reduced (thanks Avery Bedows for sparking this visual):

It shouldn’t be a surprise that reducing non-important information allows for more productivity, but we did find a downside to that as well.

Core Frustrations

In eliminating non-important information, some of us experienced anxiety around response time to “urgent,” non-important messages. The same thing that gave us freedom caused us pain.

Urgency represents a two-way relationship in a messaging paradigm, estimated by both sides. Some of us felt that we were responding too slowly to family and friends given our device limitations. In some cases, we felt we were missing out on things our friends were doing on messaging platforms that don’t work well on an Apple Watch. More importantly, some of our family and friends felt that we were responding too slowly to them without knowing about our phoneless experiment.

Sorry, but most of the messages between our family and friends aren’t that important given our prior observation about importance above: If everything were important, nothing would be important in relation to any other thing.

We view response anxiety as an unfortunate societal adaptation to our devices: Every sent message has a tinge of urgency because we all know how attached we are to our devices, so the receiver is expected to have seen the message as soon as possible. Every received message, therefore, carries the obligation to respond immediately because we know they know we’ve seen the message.

Aside from message anxiety, the other major frustration with going phoneless centered around traveling.

Our phones are more useful than we might realize when we’re in unfamiliar places. While our watches were capable of directions and Uber, we had periodic trouble using those services as easily and effectively as on our phones. This made driving to meetings more difficult, as well as getting around in cities we were visiting. Additionally, the watch doesn’t operate as a wireless hotspot, limiting our ability to stay connected on our laptops outside of public Wi-Fi.

The good news is all of these problems are solvable.

Recommendations

All four of the Loup team members that tested going phoneless feel a slightly different relationship with our phones than before. Those of us that haven’t changed notification settings plan to. Some of us have noticed we’re using our phone less, at least for now.

All four of us would go phoneless again, but with caveats. Two of us would do it again with the Apple Watch as is. Two of us would do it again with a device optimized for reduced connectivity.

Some interesting devices exist to address this problem, including old candy bar phones, but a big screen with functionality enhanced by third-party developers isn’t a bad thing. It’s the limitless content available and the notifications that come with it that can be bad, especially if productivity is your core goal.

We could see a market for a device that limits apps available on a phone to those meant for productivity, which could include maps, Uber/Lyft, airlines, hotels, cloud storage, note taking, hotspot, audiobooks, etc. The device would not allow email, Slack, and other messaging outside of traditional text. It would also not have social media, YouTube, Netflix, or other video content platforms.

As for the message anxiety problem, letting people know you’re enjoying reduced connectivity and to call in an emergency seems like a good solution. Can anything be truly urgent and important if someone isn’t willing to call you about it? An automated response about limited messaging ability could be a built-in feature for a device built for reduced distraction. Apple already does a version of this with Do Not Disturb While Driving.

At Loup we always talk about the inherent tradeoffs between freedom and safety. In the case of going phoneless, the tradeoffs seem more between types of freedom. You can choose to have the freedom of unfettered access to apps, messages, and content with the hopes that you’ll self-limit (unlikely) or you can choose to find a device with built-in restriction, giving you the freedom of greater productivity and, in our experience, happiness.

Disclaimer: We actively write about the themes in which we invest or may invest: virtual reality, augmented reality, artificial intelligence, and robotics. From time to time, we may write about companies that are in our portfolio. As managers of the portfolio, we may earn carried interest, management fees or other compensation from such portfolio. Content on this site including opinions on specific themes in technology, market estimates, and estimates and commentary regarding publicly traded or private companies is not intended for use in making any investment decisions and provided solely for informational purposes. We hold no obligation to update any of our projections and the content on this site should not be relied upon. We express no warranties about any estimates or opinions we make.