This month, a group of researchers from the University of California San Diego (UCSD) published a paper in Environmental Science and Technology reporting that there are very few cases in which operating a residential home battery reduces overall emissions—assuming that households are economically rational and trying to minimize costs.

Of course, if the battery is only discharged during periods of peak emissions and only charged when fossil fuel use is low, then a household might reduce emissions. But across 16 representative regions, operating a battery this way ended up being costly.

The results are similar to those published in Nature Energy in the beginning of 2017, although that study looked at a narrower region (99 homes in Texas) and modeled different battery software configurations.

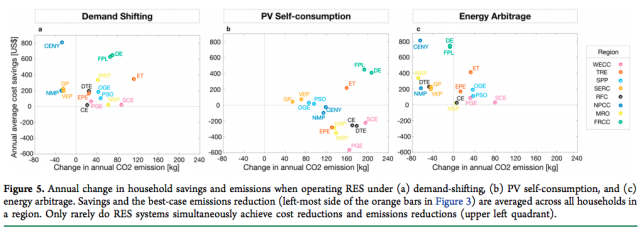

The UCSD study looks at representative homes under 16 different utilities across the country. Each utility has its own emissions profile and unique demand requirements (depending on the weather in the region). The study also looked at three different configuration possibilities:

- A demand-shifting configuration, where the battery is used to minimize costs when electricity rates vary by time of day;

- A solar self-consumption configuration, where the user has solar panels and wants to maximize the amount of energy they get from those panels; and

- An energy arbitrage configuration, where the residential battery owner can buy and sell electricity at retail rates depending on what's cheaper at the moment.

The researchers found that the only way to reliably decrease emissions using batteries is if utilities incorporate a "Social Cost of Carbon" into their pricing schemes—that is, charging people extra for using electricity during carbon-heavy periods of generation. This helps bring batteries into the emissions-reducing fold. Unfortunately, including a cost for carbon dioxide emissions has proven politically difficult.

If customers were to operate their residential batteries to reduce carbon emissions regardless of cost, the average household would cut their carbon footprint by 2.2 to 6.4 percent. "But the monetary incentive that customers would have to receive from utilities to start using their home systems with the goal of reducing emissions is equivalent to anywhere from $180 to $5,160 per metric ton of CO2," a press release from UCSD noted.

Although household batteries are only weakly tied to emissions reductions in most regions of the continental US under cost-minimizing conditions, there may be other reasons to get a battery, and there may be other reasons for utilities to push residential batteries. Some homeowners may value backup power in areas where electricity is unreliable. Utilities might support residential battery deployment to increase grid flexibility if a lot of customers are putting solar panels on their homes.

"There may be good reasons to decentralize the grid through ubiquitous installation of small RES [Residential Energy Storage], but cost-effective emissions control is not one of them at the moment," the researchers write.

Environmental Science and Technology, 2018. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b03834 (About DOIs).

reader comments

503