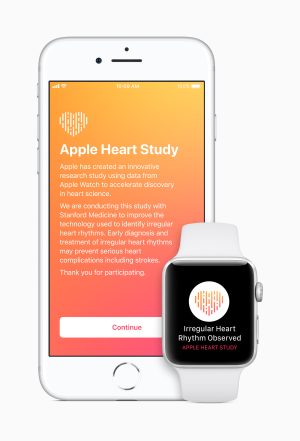

The study, dubbed the Apple Heart Study, began in November 2017, before the release of the Apple Watch Series 4, which includes an electrocardiograph (ECG) feature for monitoring heart activity. Though the study didn’t keep pace with that of wearable device development, it was rather speedy relative to clinical trials. In fact, some cardiologists were impressed simply by the short period of time in which the study was able to recruit such a large number of participants—nearly 420,000—plus follow up with them using telemedicine and get results.

Dr. Jordan Safirstein, an interventional cardiologist at the meeting, called the study “amazing,” telling STAT, “It’s a lovely demonstration of how we can enroll patients completely virtually, which I think is a huge extension for us in terms of patient engagement and enrollment.”

The study reportedly enrolled 419,297 people who had one of the earlier watches and an iPhone. Most were young people, but nearly 25,000 were aged 65 or older—the age group at the highest risk of the condition. The watches monitored for irregular heart rhythms and, if one was detected, notified the users and prompted them to set up a telemedicine consultation with a doctor involved with the study. The notified users were then able to get a separate ECG patch, which they were asked to use for a week to record their hearts’ electrical rhythms for comparison with watch data.

Pulse on the data

Overall, 2,161 participants in the study—0.5 percent—got a notification from their watch saying that they may have atrial fibrillation. Separating the participants by age, researchers found that 3.2 percent of the participants older than 65 got notifications, while 0.16 percent of those aged 22 to 39 received a notification. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that about nine percent of people aged 65 and older—not just those with Apple Watches—have atrial fibrillation, while about two percent of those younger than 65 have the condition.

Of those notified in the study, only about 450 participants received, used, and returned an ECG patch. The ECG data confirmed atrial fibrillation in just 34 percent of those 450 or so notified participants. The other two-thirds did not experience an irregular heart rhythm in the week of follow-up monitoring.

The Stanford researchers noted that “[s]ince atrial fibrillation is an intermittent condition, it’s not surprising for it to go undetected in subsequent ECG patch monitoring.”

In an interview with The Wall Street Journal, Marco Perez, a cardiovascular medicine specialist at Stanford and one of the study leaders, emphasized that the likelihood that the watch notified users of an ECG-confirmable episode of atrial fibrillation was 84 percent. But, this figure is still not very high for a medical device. It also came from an analysis involving data from just 86 of the watch-notified participants, the WSJ reports.

Overall, cardiologists at the meeting reacted with a mix of optimism and wariness. Some were hopeful that the watch could help identify heart patients that might otherwise be missed. Others worried that the watch would send false alarms to healthy people or accurate alarms to people with conditions not requiring treatment. Either of these situations could lead to unnecessary stress, anxiety, medical tests, and treatments, which have their own risks.This may “lead a lot of patients potentially to being treated unnecessarily or prematurely, or flooding doctors’ offices and cardiologists’ offices with a lot of young people,” Jeanne Poole, an expert on heart rhythm abnormalities at University of Washington in Seattle, said in a panel discussion at the meeting.

Still, others merely saw the study as a first step toward better wearable health monitors and virtual trials. The use of such mobile and wearable tech is ticking upward, particularly among older people who may be more likely to benefit from such monitoring. A 2016 survey by AARP found that 54 percent of people in their 60s already owned a smartphone and an additional 13 percent said they planned to buy one.

Listing image by Apple

reader comments

95