[Update May 17, 2019: The University of Bristol released a statement today retracting its press release claiming one of their researchers had successfully cracked the code of the Voynich manuscript:

Yesterday the University of Bristol published a story about research on the Voynich manuscript by an honorary research associate. This research was entirely the author's own work and is not affiliated with the University of Bristol, the Faculty of Arts or the Centre for Medieval Studies. ... When a member of our academic community has a paper published in a peer-reviewed journal, the University’s Media Team will determine whether the findings are of public interest. If they are, the team will communicate the research to the media and on our University website. Following media coverage, concerns have been raised about the validity of this research from academics in the fields of linguistics and medieval studies. We take such concerns very seriously and have therefore removed the story regarding this research from our website to seek further validation and allow further discussions both internally and with the journal concerned.

We leave it to the reader to ponder how an honorary research associate is a member of the university's academic community, but his controversial research paper is not affiliated with the university in any way.]

Original story

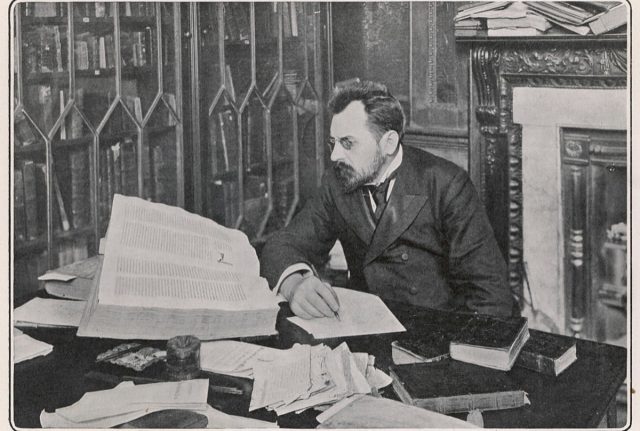

The Voynich manuscript is a famous medieval text written in a mysterious language that so far has proven to be undecipherable. Now, Gerard Cheshire, a University of Bristol academic, has announced his own solution to the conundrum in a new paper in the journal Romance Studies. Cheshire identifies the mysterious writing as a "calligraphic proto-Romance" language, and he thinks the manuscript was put together by a Dominican nun as a reference source on behalf of Maria of Castile, Queen of Aragon. Apparently it took him all of two weeks to accomplish a feat that has eluded our most brilliant scholars for at least a century.

So case closed, right? After all, headlines are already trumpeting that the "Voynich manuscript is solved," decoded by a "UK genius." Not so fast. There's a long, checkered history of people making similar claims. None of them have proved convincing to date, and medievalists are justly skeptical of Cheshire's conclusions as well.

What is this mysterious manuscript that has everyone so excited? It's a 15th century medieval handwritten text dated between 1404 and 1438, purchased in 1912 by a Polish book dealer and antiquarian named Wilfrid M. Voynich (hence its moniker). Along with the strange handwriting in an unknown language or code, the book is heavily illustrated with bizarre pictures of alien plants, naked women, strange objects, and zodiac symbols. It's currently kept at Yale University's Beinecke Library of rare books and manuscripts. Possible authors include Roger Bacon, Elizabethan astrologer/alchemist John Dee, or even Voynich himself, possibly as a hoax.

Another day, another dubious claim that someone has "decoded" the Voynich manuscript.

There are so many competing theories about what the Voynich manuscript is—most likely a compendium of herbal remedies and astrological readings, based on the bits reliably decoded thus far—and so many claims to have deciphered the text, that it's practically its own subfield of medieval studies. Both professional and amateur cryptographers (including codebreakers in both World Wars) have pored over the text, hoping to crack the puzzle.

Among the most dubious is a 2017 claim by a history researcher and television writer named Nicholas Gibbs, who published a long article in the Times Literary Supplement about how he had cracked the code. Gibbs claimed that he had figured out that the Voynich Manuscript was a women's health manual whose odd script was actually just a bunch of Latin abbreviations describing medicinal recipes. He provided two lines of translation from the text to "prove" his point. Unfortunately, said the experts, his analysis was a mix of stuff we already knew and stuff he couldn't possibly prove.

Gibbs' most vocal critic was Lisa Fagin Davis, executive director of the Medieval Academy of America. "They’re not grammatically correct. It doesn’t result in Latin that makes sense," she told The Atlantic at the time. "Frankly I’m a little surprised the TLS published it... If they had simply sent to it to the Beinecke Library, they would have rebutted it in a heartbeat."

Gibbs' motives were also questionable, as Annalee Newitz reported for Ars at the time. "Gibbs said in the TLS article that he did his research for an unnamed 'television network,'" Newitz wrote. "Given that Gibbs' main claim to fame before this article was a series of books about how to write and sell television screenplays, it seems that his goal in this research was probably to sell a television screenplay of his own."

Just last year, Ahmet Ardiç, a Turkish electrical engineer and passionate student of the Turkish language, claimed (along with his sons) that the strange text is actually a phonetic form of Old Turkish. That attempt, at least, earned the respect of Fagin Davis, who called it “one of the few solutions I’ve seen that is consistent, is repeatable, and results in sensical text.”

Cheshire argues that the text is a kind of proto-Romance language, a precursor to modern languages like Portuguese, Spanish, French, Italian, Romanian, Catalan, and Galician that he claims is now extinct because it was seldom written in official documents. (Latin was the preferred language of import). If true, that would make the Voynich manuscript the only known surviving example of such a proto-Romance language.

"Its alphabet is a combination of unfamiliar and more familiar symbols," he said. "It includes no dedicated punctuation marks, although some letters have symbol variants to indicate punctuation or phonetic accents. All of the letters are in lower case and there are no double consonants. It includes diphthong, triphthongs, quadriphthongs and even quintiphthongs for the abbreviation of phonetic components. It also includes some words and abbreviations in Latin."

-

Cheshire argues that this page shows the word "palina," a rod for measuring the depth of water.G. Cheshire

-

This page shows two women with five children in a bath. Cheshire thinks the words describe different temperaments, and those words survive in Catalan and Portuguese.G. Cheshire

Fagin Davis naturally had strong opinions about this latest dubious claim, too, tweeting, "Sorry, folks, 'proto-Romance language' is not a thing. This is just more aspirational, circular, self-fulfilling nonsense." When Ars approached her for comment, she graciously elaborated. And she didn't mince words:

As with most would-be Voynich interpreters, the logic of this proposal is circular and aspirational: he starts with a theory about what a particular series of glyphs might mean, usually because of the word's proximity to an image that he believes he can interpret. He then investigates any number of medieval Romance-language dictionaries until he finds a word that seems to suit his theory. Then he argues that because he has found a Romance-language word that fits his hypothesis, his hypothesis must be right. His "translations" from what is essentially gibberish, an amalgam of multiple languages, are themselves aspirational rather than being actual translations.

In addition, the fundamental underlying argument—that there is such a thing as one 'proto-Romance language'—is completely unsubstantiated and at odds with paleolinguistics. Finally, his association of particular glyphs with particular Latin letters is equally unsubstantiated. His work has never received true peer review, and its publication in this particular journal is no sign of peer confidence.

Ouch.

And she's not the only skeptic. "The decipherment is limited to some phrases and words, and I don't find any translation of a longer passage. I am not a medieval (Vulgar) Latin expert, so I can't comment on the plausibility of individual words," said Greg Kondrak, a natural language processing expert at the University of Alberta who has used AI to try and decode the Voynich manuscript. "The part of the paper which is devoted to the Zodiac sign names seems to make most sense, but the fact that those names are of Romance origin is well known, and they seem to have been added to the manuscript after it was completed. Regarding the decipherment of the individual symbols, a number of people have come up with a mapping to Latin letters, but those mappings rarely agree with each other, or with this proposal."

So another day, another dubious claim that someone has "decoded" the Voynich manuscript. Look, it's a fascinating topic, and it's always fun to have an excuse to dive down the rabbit hole of medieval manuscripts, mysticism, and cryptography, reveling in all the various theories that continue to be propounded about this mysterious treatise. But a word of advice: the next time someone claims to have finally deciphered the Voynich manuscript—of course there will be a next time—take a deep breath and check with your local medievalist before excitedly glomming onto the claim. (For an in-depth analysis of some of the issues scholars are having with Cheshire's work, see this blog post by J.K. Peterson at The Voynich Portal. UPDATE: Here is a follow-up post.)

What would it take to convince scholars like Fagin Davis? She outlined her criteria in a follow-up tweet: "(1) sound first principles; (2) reproducible by others; (3) conformance to linguistic and codicological facts; (4) text that makes sense; (5) logical correspondence of text and illustration. No one has checked all of those boxes yet."

DOI: Romance Studies, 2019. 10.1080/02639904.2019.1599566 (About DOIs).

reader comments

158