Apple’s splashy new product announcements at its annual Worldwide Developers Conference in San Jose also ushered in new rules of the road for its ecosystem partners that force hard turns for app makers around data ownership and control. These changes could fundamentally shift how consumers perceive and value control over the data they generate in using their devices, and that shift could change the landscape for how services are bought, consumed and sold.

A lot of privacy advocates have posited a future wherein we ascribe value to the data of individuals and potentially compensate people directly for its use. But others have also rightly pointed out than in isolation, a single individual’s data is precisely value-less, since it’s only in aggregate that this data is worth anything to the companies that currently harvest it to inform their marketing and drive their product decisions.

There are many reasons why it seems unlikely that any of the companies for which user data is a primary source of revenue or a crucial aspect of their business model would shift to a direct compensation model – not the least of which is that it’s probably much cheaper, and definitely much more scalable, to build products that provide them use value in exchange instead. But that doesn’t mean privacy won’t become a crucial lever in the information economy of the next wave of innovation and tech product development.

Perils of per datum pricing

As mentioned, the mechanics of directly selling your data to a company are problematic at best, and unworkable at worst.

One big issue with this is that there’s definitely bound to be a scale limit on any subscription paid product. In a world where that’s increasingly a preferred method for media companies, food and packaged goods delivery, and even car ownership alternatives, there’s clearly a cap on how much of their income consumers are willing to commit to these kinds of recurring costs.

User populations in the billions are almost certainly out of reach for anyone opting into subscriptions, and that’s incompatible with the DNA of a company like Facebook.

Speaking of Facebook, it’s worth looking into how it, and Google exchange services for data in the most basic sense to get a better idea of how a direct payment model for data doesn’t scale from a technical perspective, either.

When Facebook or Google develop a new product, it has costs, and costs that can be impacted by a consideration of the scale of its use; more users necessarily incur higher data center costs, for example. But the core cost of building the software (ignoring, for a second, maintenance and updates) is essentially fixed, and one-time.

You invest upfront to build the thing, then you deploy and recoup your build costs on usage and scale, with (again, in the realm of theory) an endless tail on future revenue generation. The product pays for itself pretty quickly, and then generates revenue mostly passively thereafter, excluding debugging and feature improvement development costs.

Paying for data directly introduces a very different kind of model, with an ongoing fixed cost (again, assuming a pretty basic model – you could also imagine a world in which there’s some kind of slope or adjustment for data volume over time). It’s the kind of shift that changes your entire incentive structure, and will likely overhaul not just how you deploy products, but how you shape your corporate culture, since there’s less cause to focus on shipping new stuff.

At this point, we haven’t even considered how to actually price and value the data generated by an individual user, which itself seems like a Gordian knot to untie. What qualifies as a fair market rate for data on an individual level, when, as mentioned above, it only really acquires value on the open market when taken in aggregate? And surely you have to still put some kind of value and allow margin for actual product development, as part of the value mix on top of direct payouts.

So what happens instead?

Pay-for-data models seem unlikely to take root, at least not with more seismic shifts than we’re seeing now in the locus of influence and control among the companies leading the tech industry. The revelations and apparent uproar about user privacy seem to continue and grow louder, but it’s not really unmooring the giants from their perches just yet, and in many cases, they continue to show signs of increased success.

But even if it’s not toppling giants, the privacy turn in the broader conversation presents a lot of opportunity for companies willing to invest and build around different models with more compatible incentive structures. The one clear and obvious example of a company doing this is Apple.

As I wrote about during Apple’s WWDC keynote, the company is clearly making bigger moves when it comes to truly developing privacy as a differentiator for their products. Apple’s products have always featured privacy as a feature relative to other FAANG peers like Google and Facebook, but for a long time, that was coincidental, rather than intentional – Apple’s revenue model has long been about pushing hardware sales, and to date, all of its services work has been in service of making said hardware a better value (and arguably adding lock-in) for its users.

Over the past several quarters, we’ve seen Apple emphasize its services business, especially in its earnings reports and investor calls with CEO Tim Cook. And Apple’s services business benefits from the existing incentive structure that helped it build a hardware business that generally respects a user’s privacy.

The question has always been to what extent that incentive structure remains intact as Apple’s services business shifts from being primarily a driver of its hardware sales, to a business in its own right, likely evaluated on the merits of its own profit and loss statement.

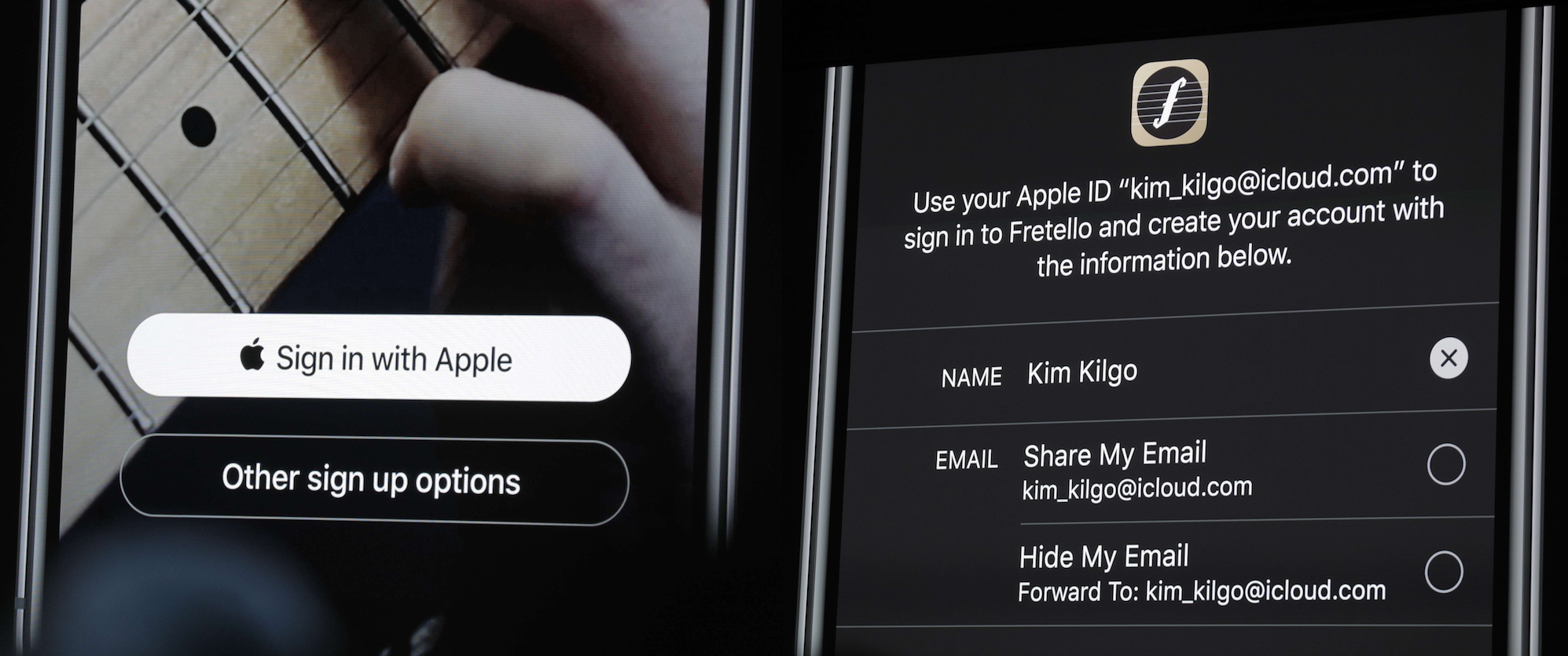

The answer, so far, seems to be that Apple is not only keeping that incentive structure intact, but leaning into it – its WWDC announcements included its boldest move yet in privacy as a selling point, a new single-sign on facility called “Sign in with Apple” that it’s making mandatory for all developers that offer other SSO options, including Facebook and Google’s authentication methods.

Apple’s sign-on is everything that consumers want from this type of thing – low friction, integrated with device auth methods like Face ID and Touch ID – and nothing they don’t want (laden with persistent tracking). It can still provide the benefits of a direct relationship between consumer and service provider via opt-in name and email (or tokenized, single-use email replacement) sharing, with none of the additional trade-offs that come with the added layers of less visible consent layered into these types of registration methods.

Sustainably incentivized privacy-as-a-service

Apple’s example brings us to a model for a third option, which exists between paying people directly for use of their data, and making people the product via free services that have onerous trade-offs when it comes to use of your info.

The trick, of course, is finding the appropriate base-level incentive structure that ensures the service provider continues to respect the user’s privacy, and can build a sustainable business while also offering true and transparent privacy control to a user. Hardware, with its fixed costs and defined margins, is one way to make this work – but it’s not the only one.

Apple’s other big WWDC privacy move is a place to look for examples of how other businesses might take root and grow in this emerging space of privacy service layer providers. Specifically, Apple is providing on-device footage analysis of video captured by HomeKit enabled cameras, and delivering the consumer benefit that results (ie, identifying if someone approaches your house) without extracting the consumer cost (ie, sharing this data back to a cloud service provider in any personally identifiable, or even generically useful format).

Here again, Apple is able to do this primarily because they’re a platform with market-leading scale, and they have the customers that their hardware maker partners need access to. But the model could work for SaaS providers that seek to act as an intermediary layer, one that can provide functional value by unifying an ecosystem of many independent providers and a global customer base.

Overall, tech has trended toward disintermediation. But there’s a unique opportunity now for an economy based on introducing an insulating layer that can protect customers while providing selective, opt-in and more direct value to service providers and people who just want to sell things directly to their customers — and who are willing to take that individual data-sharing relationship seriously without the upside of exploiting that data by distributing it on to third parties.

Selective opt-in, tokenization and transparent controls are all product opportunities with strong consumer demand, ready for their moment in the sun; all that’s left is determining what the best drivers are for making these amenable and enticing to the high-demand connected services that already exist and the companies that build them.