It started with a brief pause, an inhalation of breath, and a mock turtleneck.

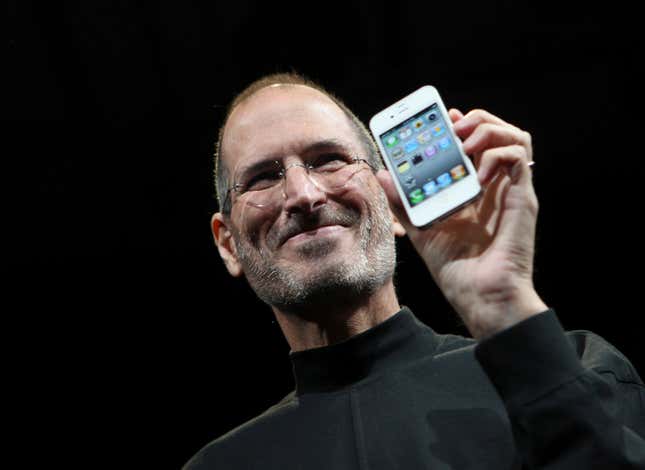

“This is a day I’ve been looking forward to for two-and-a-half years,” Apple co-founder and then-CEO Steve Jobs said onstage at the 2007 Macworld convention. “Every once in a while, a revolutionary product comes along that changes everything.”

Jobs paced slowly across the stage, then said Apple was fortunate enough to be releasing three revolutionary products that day: a “widescreen iPod with touch controls,” a “revolutionary mobile phone,” and a “breakthrough internet communications device.” He kept repeating, “an iPod, a phone, and an internet communicator.” Cheers grew as the audience caught on. “These are not three separate devices,” Jobs said. “This is one device, and we are calling it iPhone.”

The iPhone turned Apple from a successful computer company into the world’s most profitable consumer electronics operation. Over the past seven years alone, it has generated more than $1.5 trillion in revenue, and around $337 billion in profit. In that time, iPhone sales have generally accounted for between 50% and 70% of Apple’s quarterly revenue. It’s safe to say that Apple would not be the same company it is today without the iPhone’s unbridled success.

But that success could also spell Apple’s undoing. The iPhone has changed the computer and smartphone landscape so dramatically that without proper planning, it could lead Apple down a path of retrenchment. Already, the phone faces steep competition, a saturation point on incremental upgrades, and consumers’ diminishing tolerance for price increases. To counter the iPhone’s flagging revenue, Apple has begun expanding its ecosystem—if the company that made your favorite computer-phone can also get you to use it for everyday health, financial, entertainment, and perhaps even automotive needs, that device becomes just one in a network of gadgets and services that keep consumers tethered to Apple. But each new venture presents its own challenges, which together will test Apple’s talent for disruption more than perhaps ever in its history.

Table of contents

Why does Apple even need a next iPhone? • Okay well, could it be iCloud? • What about Apple Pay? • Or Apple News? • Maybe Apple Music? • Perhaps Apple Arcade? • Okay, what about Apple TV+? • The Apple Watch? • Augmented-reality glasses? • Putting Siri everywhere? • A self-driving car?! • Is this ecosystem enough?

Fighting against a commodity

For the most part, Apple is still operating under the halo of the iPhone. The structures Tim Cook helped build as chief operating officer, and then CEO, have created a self-perpetuating revenue model in which customers know Apple will release a newer version of its products every year.

But that halo is starting to dim. On Jan. 2, 2019, the first stock-market trading day of the year, Cook halted trading in Apple stock; in a note to investors, he said the company needed to reforecast its guidance for the recent holiday quarter. It was the first time Apple had to reforecast under Cook, and the first time it had done so since before the iPhone was released. Cook blamed weak revenue on foreign exchange “headwinds” and the need to discount replacement batteries on older phones. But the real culprit was China—consumers there weren’t buying as many iPhones as Apple expected.

Apple generated $18 billion in revenue in China in the holiday quarter of 2017, but it hasn’t come close to that number since. Most recently, revenue growth has fallen for three straight quarters compared to the same periods a year earlier. And while there are challenges to selling in China, including the government imposing stricter restrictions on US companies operating there, most of the issues are of Apple’s own making.

In many nations, the smartphone has rapidly gone from a niche luxury item to a commodity product. As the middle classes in nations like China and India gain spending power, smartphone manufacturers are springing up to fill their needs. Top-of-the-line smartphone specifications are available in affordable phones a year later, and manufacturers closer to their sources of production can lower costs even further. It turns out that outside the US, consumers aren’t as swayed by Apple’s luster as they are phones at prices they can afford.

In developing Asian nations, Apple’s initial strategy wasn’t to produce new iPhones aimed at more price-conscious consumers, but to just sell them old phones. That hubristic move didn’t pay off—Apple’s growth stagnated in the region, and fell precipitously in China. The company recently nixed this approach in favor of offering the same models it does everywhere else. Around the same time, Apple appointed Nokia veteran Ashish Chowdhary as the third chief of its India business in as many years. Michael Coulomb, Chowdhary’s predecessor, paid attention in earnest to Apple’s growth in India, but the company struggled to unseat younger upstarts with quality devices, like China’s OnePlus.

The updated strategy in India is to price new models, including the iPhone 11, competitively. Apple dropped the price on the iPhone Xr in India earlier in the year, and sales shot up. Revenue for Apple’s “rest of Asia” region (which includes India, but not China or Japan) jumped by more than 13% in the most recent quarter, to about $3.6 billion. Analysts are expecting another uptick once the iPhone 11 goes on sale, with a starting price roughly 18% lower than the iPhone Xr went for after its launch last year.

The company is also deepening its ties to India. Apple plans to open its first retail store in the country in the near future, and is building a dedicated Indian web presence, increasing the number of phones built in the country, and creating a dedicated support system for Indian developers.

In China, the story is a little different. Apple promoted its longtime wireless exec, Isabel Ge Mahe, to the newly created position of managing director of Greater China in 2017. Ge is also trying to foster support for local developers, but that’s just one of many initiatives. Apple has tried to get on Chinese regulators’ good side by investing in local companies—it put $1 billion into ride-hailing app Didi Chuxing—and building research-and-development centers across the country. Ge has also worked to produce China-specific features for Apple products, including dual-SIM phones, to help it keep up with local demands. “We want to offer better localized services,” she told China Daily in July. “That is what I have been constantly pushing forward and what I like most.”

Unlike Google, whose employees are raising existential questions about what the company’s censored search site in China signals about its values, Apple’s China work is relatively uncontroversial. That might be because Apple relies heavily on China for its supply chain, and so has always worked directly with regulators to tiptoe carefully around government demands. (Just last month, Apple removed the Quartz app from the Chinese App Store for containing “content that is illegal in China,” which could refer to our extensive coverage of the Hong Kong protests.) With all its homegrown competition, China has little incentive to actively court Apple, but Apple has every incentive to do what it needs to to keep adding Chinese customers.

Ironically, the bigger threat to Apple’s China supply chain might be closer to home. As Cook explained to US president Donald Trump over dinner in August, the ongoing trade war between the US and China could make it harder for Apple to compete with Samsung. An escalation of US tariffs on Chinese imports may not hamper the company’s ambitions for Chinese consumers directly, but could still impact the iPhone’s bottom line.

It’s too early to say whether Apple’s Asia efforts will be enough to persuade developers and consumers that Apple is an integral part of their lives. But there are already positive signs—the company is getting close to returning to growth in China, and growing again in India, albeit on a far smaller scale than in China or its other established markets.

Hitting the upgrade ceiling

Since the iPhone’s second generation, the iPhone 3G, the device has been on a two-year refresh cycle. Every other year, Apple introduces a new number (4, 5, 6) and ushers in a new aesthetic and form factor. In the intervening years, the “S” years, Apple follows its new models up with internal refinements and hardware updates, i.e. the 4s, 5s, and 6s. Traditional US cellular contracts lasted two years, so consumers could decide whether to upgrade on number years or S years. True Apple acolytes might do both.

But as smartphones improve, it’s increasingly difficult to differentiate one from another in terms of power, battery life, screen resolution, and just about everything else the average consumer cares about. It’s also getting harder to sell a new iPhone over the one users already have, mainly because they’re so well-built. In recent years, the average time a consumer holds on to their phone has increased to around 33 months, as carriers have almost entirely moved away from forcing customers to sign two-year phone contracts. For that reason, Apple’s iPhone problems extend beyond emerging markets: Its overall revenue has been contracting in Europe for three straight quarters, and growth has fallen to almost nil in North America.

The Americas region is far and away Apple’s most lucrative, accounting for nearly half of its $54 billion in revenue in the most recent quarter, and the US makes up a sizable chunk of that market. As upgrades slowed, Apple was left with two options: Start contracting, or try to get more money out of its most loyal users. So the company’s plan for its most valuable customers is having them pay more for iPhones, and for more services.

In 2012, the last year that Apple didn’t release multiple phone models, the iPhone started at $649. In 2014, Apple started offering different sizes of iPhone, in an attempt to upsell consumers. It released the iPhone 6 ($649) and 6 Plus ($769), the latter having slightly better internal components and a larger display. By 2018, it had fragmented offerings even more, releasing a “lower-cost” model along with a flagship device that came in two sizes. Throughout, Apple kept slowly increasing the price of its lowest-cost iPhone while massively upping the price of its highest-cost iPhone, making the other ones seem affordable by contrast. The company’s 2018 models, the iPhone Xr, Xs, and Xs Max, started at $749, $999, and $1,099, respectively.

This strategy worked for a while, especially in the US. But in mid-2019, the share of Apple’s revenue that came from the iPhone fell to its lowest rate in nearly a decade, suggesting the company had hit its consumers’ price ceiling. At the most recent iPhone launch event, Apple lowered the price on its lowest-cost device, the iPhone 11, to $699. While not quite the original iPhone price (although if you factor in inflation, it’s actually a better deal), that’s still a drop of $50 over the prior year.

Apple stopped reporting individual unit sales of its products in 2018. After a few years of nearly flat iPhone-shipment growth, it’s not surprising that the company would want to obfuscate that figure.

At the time, chief financial officer Luca Maestri argued that there was no longer a correlation between iPhone sales growth and strong iPhone revenue, presumably because the price of iPhones now varies wildly by model. If a large share of customers chose higher-end models, Apple could be selling fewer iPhones but making the same amount of revenue. Except that doesn’t seem to be what’s happening: iPhone revenue is falling, regardless of how many devices Apple sells.

A service solution

Even as iPhone sales stagnate, Apple’s overall revenue hasn’t tumbled. Its other core hardware businesses, sales of Mac computers and iPad tablets, have stayed relatively consistent over the past few years. Meanwhile, two other parts of its business are growing rapidly.

One is Apple’s “wearables, home and accessories” business unit (previously reported as “other products”), which includes sales of the Apple Watch, AirPods, and Beats headphones. That division’s revenue surged in recent quarters, generating $5.5 billion in the most recent one, a jump of nearly 50% over the same period last year. Analysts attribute the gains to the AirPods’ popularity and the increasingly refined Apple Watch. But even though $5 billion is more than some Fortune 500 companies make in a year, it’s still tiny compared to Apple’s other new area of focus.

For nearly three years, Apple’s services arm has been the company’s second-largest business. It has completely broken the seasonality of most of Apple’s revenue, and increased sequentially in size nearly every quarter since 2011. This business segment includes a wide swath of Apple’s non-hardware offerings, from AppleCare warranty support, to revenue from Apple Pay transactions, to iCloud storage, down to sales of apps, games, music, and movies through its app stores. Over the past four quarters, services has generated nearly $44 billion in revenue for Apple, which would put that business line at 70th on the Fortune 500 list, above companies such as American Express, Oracle, Nike, 3M, and Coca-Cola.

iCloud

In 2008, along with the launch of the iPhone 3G, Jobs unveiled MobileMe, Apple’s first comprehensive attempt to build a cloud-storage service for its customers. For $99 a year, users could sync photos, videos, contacts, calendars, documents, and emails across all their Apple devices. At least that was the plan. The launch was marred by outages and glitches, leading Jobs to send an internal email describing it as “not our finest hour.” The cloud service ultimately took a backseat to Apple’s other 2008 reveals, which included the App Store and a new iPhone.

Apple replaced MobileMe with iCloud in 2011, finally shutting down its original cloud service midway through 2012. The new service was meant to simplify and modernize Apple’s cloud offerings. Customers currently get 5GB of cloud storage to use across their devices for free, and can choose to pay $1, $3, or $10 per month to get 50GB, 200GB, or 2TB of cloud storage space.

In theory, iCloud allows users to do the same sorts of things as MobileMe did; it even has an online hub accessible from anywhere on iCloud.com. But in practice, the service is muddled, with features that lag behind many of the other popular cloud services on the market.

In 2014, The Information reported that Apple’s issues with cloud stem from the fact that, unlike many of its competitors, Apple lacks a core team working on the infrastructure of iCloud. But Apple’s services are also just expensive for what they are. Some competitors, like Google’s Drive, offer far more storage for free (15GB to iCloud’s 5GB), and others, like Microsoft’s OneDrive, bundle in considerable storage space with purchases of other software, like Office365.

Apple Pay

Apple launched its mobile-payment program, Apple Pay, in 2014, with the grand vision of fixing what Cook saw as a broken payments industry. It took time to find its footing—customers, merchants, and banks had to get on board–but according to some estimates, Apple Pay is becoming a massive success, especially in regions where contactless cards account for over 25% of payments. Cook said Apple handled 1.8 billion payment transactions in the last three months of 2018, which means 1.8 billion (admittedly small) transaction fees to Apple.

In the US, where payment models have been relatively unchanged since Mastercard introduced the magnetic-stripe card and Visa the point-of-sale terminal in 1979, consumers have been slower to adopt Apple Pay. Only 12% of Apple Pay’s users are currently based in the US.

That could be changing. Every new iPhone sold has the ability to use Apple Pay, and merchants and organizations are changing their stance on the service. Target and CVS, two of the US’s largest retailers, rolled out Apple Pay support after initially balking. Major transit systems, like New York’s Metro and Chicago’s CTA, are testing accepting contactless payments, and working directly with Apple to accept its technology.

Apple isn’t stopping there. The company recently launched the Apple Card, a combination of a physical credit card backed by Mastercard and Goldman Sachs, and a digital one that lives in the iPhone’s Apple Wallet app. Apple will make money from interest fees and interchange fees between payment companies.

Between Apple Pay, the Wallet app—which increasingly incorporates loyalty cards, student IDs, and digital keys—and the Card, Apple is setting itself up to be the company that kills the wallet.

News and entertainment

After launching streaming service Apple Music in 2015, Apple in 2019 released Apple Arcade, a $5-per-month service offering exclusive indie games that work on just about every device Apple makes; as well as Apple News+, which offers a host of articles from popular magazines (and one newspaper) for $10 a month. The company is increasingly interested in being its consumers’ chief connection to all types of content.

Apple Music currently has around 60 million subscribers, services SVP Eddy Cue said earlier this year. Like its chief competitor Spotify, Apple Music costs $10 per month, and features exclusive music, as well as the ability to download albums for offline listening. But some consumers have found it difficult to use. Meanwhile, Spotify has around 108 million paid subscribers, and 232 million users from whom it can generate advertising revenue.

Apple News+ now boasts over 300 magazines, but Apple struggled to convince publishers to join, in part because doing so requires handing over 50% of the attendant subscription revenue, a considerably higher cut than on any comparable service. In April, the New York Times reported that even with a one-month free trial, the service had only secured around 200,000 subscribers. Apple has not itself disclosed any subscriber figures.

But when it comes to content, no Apple bet is more outside the company’s comfort zone than the one it’s making on TV.

Apple TV+

Although Apple upended the record industry by introducing individual song downloads on iTunes, it never felt the need to launch its own record label. With Apple TV+, the company is effectively doing just that: For $5 a month, it will offer a host of original content produced exclusively for the tech giant.

In the streaming wars, Apple is at a disadvantage: It doesn’t own any compelling intellectual property. When Disney launches its streaming service, Disney+, in November, it will be with an enormous back catalog of Disney movies, plus past and future iterations of Star Wars and Marvel movies and shows. Disney can develop countless spin-offs, reboots, sequels, and new storylines in existing worlds, using characters and places audiences already know and love. HBO, with shows like Westworld, The Sopranos, and Game of Thrones—and the credibility that comes with having developed them—can likewise build on existing worlds, or rest on the laurels of a deep back catalogue. Even other upstart streaming services, like CBS All Access (home of Star Trek and Twilight Zone reboots), or NBC’s Peacock (The Office; need I say more?) have deep catalogues and original IP to work with. Apple is building its worlds from scratch.

To meet this challenge, the company has for years been amassing talent from across Hollywood. At an event in March, Apple trotted out luminaries like Steven Spielberg, Oprah Winfrey, J.J. Abrams, Reese Witherspoon, and even Big Bird to preview some of its forthcoming projects.

But relationships with some of those creatives are already strained. Abrams, one of the creative forces behind Disney’s latest Star Wars films and Paramount’s movie reboot of Star Trek, reportedly walked away from a $500 million-plus deal with Apple because it wouldn’t have allowed his production company to work on outside projects. Tim Cook also ruffled feathers when he told Apple’s TV team to nix any undue profanity, sex, or violence in its programming. The Wall Street Journal reported that Cook even asked director M. Night Shyamalan to remove crucifixes from a psychological thriller he was developing for the service.

The worlds Apple has started to build also leave something to be desired. See, the company’s forthcoming attempt at Game of Thrones-like success, is set in a tribalistic future where everyone in the world is blind except for Aquaman actor Jason Momoa’s children. Newsroom drama The Morning Show is cast like a comedy, and a comedy show about the life of Emily Dickinson is cast like a drama. Apple is also going wide, creating sci-fi shows, thrillers, children’s shows, dramas, animated sitcoms, reality TV, and adaptations of famous books. It’s a lot to process, and the company has no reputation as a content creator to draw on.

To start, it may not need that reputation. As part of the iPhone 11 launch, Apple said it would throw in a free year of Apple TV+ to anyone who bought a new iPhone or iPad. The service is already priced aggressively—Netflix costs between $9 and $16 per month—but with 1.4 billion active iOS customers, Apple is smart to try and capture some portion of its existing fan base.

“It makes sense—they want to add value to devices they sell, and give you more reasons to stay in the Apple ecosystem,” says Rich Greenfield, an analyst at LightShed Partners who covers the streaming industry. “In addition, they are not starting with a vast library, so making it free initially to device-buyers lets lots of people get exposed to the service while the content builds.”

Greenfield calls Apple’s approach ambitious, and says the company is likely matching heavy-hitters like Disney in terms of spending on new content. When Apple hired Jamie Erlicht and Zack Van Amburg, seasoned TV executives from Sony, reports suggested it was ready to spend around $1 billion on original content. Greenfield pegs it at closer to $2 billion.

There are rumors of Apple working with record labels and production houses to create a bundle service—customers would pay $13 per month for Apple Music and Apple TV+—but discussions are still in the early stages (paywall). Whether such a bundle would make either individual service more compelling is unclear, but the idea does show Apple’s willingness to think holistically about its ecosystem. An Apple version of Amazon Prime could be on the horizon.

The elephant in the room

There’s no denying that Apple’s services business is growing, and with a cash pile of over $200 billion, the company can afford to subsidize its new ventures. But like IBM before it, Apple is losing some of its flair for innovation, growing complacent with minor upgrades to flagship products, spending heavily on research without much to show for it, and leaning on an entrenched leadership team that lacks the stubborn-but-clear vision of Steve Jobs or the design work of Jony Ive. “IBM has kept investors waiting for years for its so-called strategic initiatives… to make up for the decline in its core products,” Peter Cohan wrote in Forbes. “Like Apple, IBM is skilled at putting words into the CEO’s mouth that fail to address the elephant in the room.”

Apple can keep tiptoeing around its elephant for now, but if iPhone sales continue to falter, the company will need more than services revenue—which were around $11.5 billion in the most recent quarter, to the iPhone’s $26 billion—to pick up the slack. At the moment, Apple’s near-term bets seem focused on three main areas: health, augmented reality, and the internet of things.

Health

Since the launch of the Apple Watch in 2015, Apple has been pushing deeper into health technology. Cook said last year that he wants the company to make a “significant contribution” to the health-care industry, and Apple reportedly hired Christine Curry, an obstetrician who led the clinical response to the Zika virus in South Florida, along with a roster of other doctors to help fill out its health work.

The first Apple Watch could track your heart rate. Newer models can help you control your anxiety through breathing, alert you to irregular heartbeats, notify emergency services if you take a hard fall, identify whether the environment you’re in is too loud, pull your medical records from your iPhone, and even perform a rudimentary electrocardiogram (EKG), a function for which Apple had to secure speedy clearance from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Hospitals and health-insurance providers are starting to develop programs around the device.

Apple is also working with influential research facilities and hospitals to gather data on different medical conditions, which has helped it build software to detect things like atrial fibrillation. Later this year, it will launch a new app called Research, which bundles health studies that allow Watch owners to track how active they are, how good their hearing is, and their menstrual cycles.

It’s easy to imagine where Apple could take the Watch as battery life and connectivity improve: Future versions could be used to track sleep, test blood sugar, monitor blood pressure, and even assess blood-oxygen levels. These would all require breakthroughs in technology, and surviving regulatory hurdles, but patent applications suggest the company is interested in all of the above.

Augmented reality

During an earnings call in 2016, at the height of the Pokémon Go game craze, Cook was asked his thoughts on augmented reality. “We are high on AR for the long run,” he said. “We think there’s great things for customers and a great commercial opportunity. And so we’re investing, and the number one thing is to make sure our products work well with other developers’ kind of products.”

At least some of that investment is going toward another wearable: connected glasses, which Apple has been working on for years. A person with knowledge of the project, who saw design mockups in 2016, told Quartz at the time that the glasses would perform similar functions to the Apple Watch, except with information overlaid onto a lens in the wearer’s field of vision.

In 2017, a year after Cook’s comments on augmented reality, Apple released ARKit, a development framework for AR applications that could run on any new iOS device without blowing through the battery. Later that year, the company unveiled the iPhone X, its first smartphone built with multiple face-tracking sensors and native AR support. The iPhone X can track a user’s face down to minute movements, making for some great Snapchat-like filters, and the dual rear cameras allowed it to perceive depth and create accurate overlays onto the real world. Apple refined this technology with the launch of the iPhone Xs and iPhone 11 Pro.

Though Apple hasn’t given any indication as to whether or when it plans to release AR glasses, there are signs that we could see a product in the near future. It has been suggested that the company is working on a “reality operating system,” and Apple appeared to leave in references to some sort of AR wearable in the code for its iOS 13 operating system, released in September. Found by developer Steve Troughton-Smith, the code suggests iPhones could be used to output a stereoscopic display (perfect for showing something to two eyes), and references testing “HMEs,” an acronym that could be related to HMDs, or head-mounted displays—i.e. AR glasses.

Apple also recently announced a $250 million investment in US glass producer Corning, which has made the glass for every generation of iPhone and iPad. Analysts think the investment suggests that AR glasses are coming soon, perhaps as soon as 2020.

Siri everywhere

Originally conceived as a virtual assistant that lives in your iPhone—a supremely novel idea when it was unveiled in 2011—Siri has since become an integral component of many other Apple products. If you’re holding your iPhone, wearing newer AirPods, or in the same room as a HomePod, you need only call out “Hey Siri” to summon the virtual assistant. Apple has also built an impressive library of partners that allow Siri to work with many popular apps and top internet-of-things developers.

Much like Amazon and Google, Apple is trying to be the glue that holds the smart home together. To date, those ambitions have been limited—there’s only version of the costly HomePod, and reports suggest it hasn’t sold fantastically well—but there are signs of more initiatives in store. Apple is reportedly is working on a connected tracking device, much like the ones produced by Tile, where a user could ask Siri, or even use AR, to find something they’ve affixed a tracker to.

The company might also be working on a smaller HomePod, which could better compete with smart speakers produced by Google and Amazon, and patents purchased by Apple suggest it may also be working on a smart camera to compete with Google’s Nest.

Perhaps the most obvious indicator of Apple’s smart-home gadgetry ambitions is its decision earlier this year to rename its “other products” business reporting line to “wearables, home and accessories.”

iPhone on wheels

There is an argument to be made that Apple’s current portfolio of products, coupled with its newer areas of interest, point the way to what’s next for the company. But it’s not clear that these initiatives alone would be enough to keep the company’s revenue and profit figures where they are today. Something else is needed.

Since the release of the original iPhone, Apple has spent roughly $65 billion on research. While some portion of that money has surely gone toward projects we know about, it seems possible that a large chunk of it is being spent on longer-term work that hasn’t yet been realized. Including, potentially, a car.

Since the Wall Street Journal first reported it in 2015, there’s been some degree of consensus that Apple is working on automotive technology. Referred to internally as “Titan,” the project has grown and contracted over time, and most recently seems focused on the development of a self-driving car.

In 2017, Apple registered with the California motor-vehicle department to legally test autonomous vehicles near its headquarters. The usually secretive company even posted some of its research on the field, showing how its vehicles see the world. Apple is working with major car companies on the effort, and currently has dozens of job openings related to autonomous driving systems. This summer, Apple purchased self-driving car startup Drive.ai.

Cook once called Apple’s autonomous-vehicle work “the mother of all AI projects,” but he has also downplayed rumors that the company is looking to build its own cars, versus developing the technology that goes into them. That would be a surprising departure for Apple, which is still primarily a hardware company that builds proprietary software for its own products. The car division’s leadership team, which reportedly includes Doug Field, a former Apple hardware engineering VP who also spent five years overseeing engineering for Tesla, and Steve McManus, who has done stints at Tesla, Aston Martin, Jaguar-Land Rover, and Bentley, among others, suggests that hardware is at least not unimportant to the project.

So what comes next?

iCloud. Apple Pay. Apple Music. Apple Arcade. Apple News+, Apple TV+, Apple Watch, HomePod, connected glasses, a self-driving car. At the moment, it doesn’t seem like there’s going to be one monolithic product with enough momentum to replace the iPhone. Apple’s flagship device is for the foreseeable future an integral part of its revenue, and its newer bets are mainly supplementary devices and services meant to connect and integrate with the phone. If no one thing can replace the iPhone, Apple will make sure it provides an invaluable ecosystem for iPhone customers, one that includes everything from banking and health care to entertainment and communication.

Eventually though, Apple’s shine will dim without another dramatic shift in its core business. The smartphone will not remain the form factor preferred by the world forever, and as Henry Ford (may or may not have) said, “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.” To pull off a shift like that, you have to realize that any industry, of any size, can be disrupted. And you need a leader who is willing to alienate everyone and not take no for an answer.

Corning’s announcement of Apple’s recent investment mentions a story that Apple COO Jeff Williams told an audience of plant workers, reporters, and business and community leaders at Corning’s Harrodsburg, Kentucky facility. When Jobs introduced the original iPhone to the world, Williams said, the prototype’s screen actually featured hard plastic instead of glass. The world loved it, but Jobs swiftly called his COO to complain that carrying the device in his pocket scratched the screen.

“He said, ‘We need glass,'” Williams told the group. “And I said, within three to four years, technology may evolve…. He said, ‘No, when it ships in June it needs to be glass. I don’t know how we’re going to do it, but when it ships in June it’s gotta be glass.'”

As we know, the iPhone ultimately shipped with a glass display. Would Tim Cook have been as militant about the touchscreen had he been the one making that call? It’s hard to say. But to change the world again and maintain its bottom line, Apple will eventually need to stop limiting itself to selling faster horses.