A4 to A5: How Apple outflanked its fragmented competition in silicon

Apple's A4 project helped deliver the custom silicon for the very first iPad, positioning the company in a race against time with the world's leading mobile chip designers. Although it ran into stiff competition along the way, Apple succeeded with an implementation that was markedly different from its peers. Here's how they did it.

26 years of platform establishment in just 6

IBM's 1982 selection of an Intel processor for the original PC incrementally snowballed into the vast critical mass of an installed base of users that funded constant enhancement of the x86 architecture. The profits Intel was earning from sales of millions of x86 chips actually allowed it to transcend architectural deficiencies in its original design.

Intel could even incorporate concepts from competing RISC architectures while remaining compatible with the increasingly large installed base of DOS and Windows software developed for x86. By 1995 the global installed base of PCs— over 90% of which were x86 machines— reached 242 million. By 2002 it had passed a half billion, and by 2008 it exceeded 1 billion.

In 2008, Apple initiated its A4 project and began using the chip in 2010. Just six years later, Apple announced that it had reached an active installed base of 1 billion devices on its own— over 90% of which were powered by its Ax processors.

An installed base of that size and scale had taken 26 years to develop in PCs, and required the combined sales of every PC maker contributing to Intel's power and weight. Apple achieved this on its own. Conversely, that also means Apple's vast sales of premium iOS hardware did not contribute to its competitors' third party silicon development. And in tandem, the suffering sales of higher-end iOS competitors proved detrimental to outside silicon advancement.

A motive for A4 and beyond

Over just the course of 2010, Apple shifted from building mobile devices using fairly generic Samsung parts to releasing its new iPad, iPhone 4, the fourth generation 4G iPod touch, and a new iOS-based Apple TV all using its freshly developed A4 custom SoC funded in partnership with Samsung.

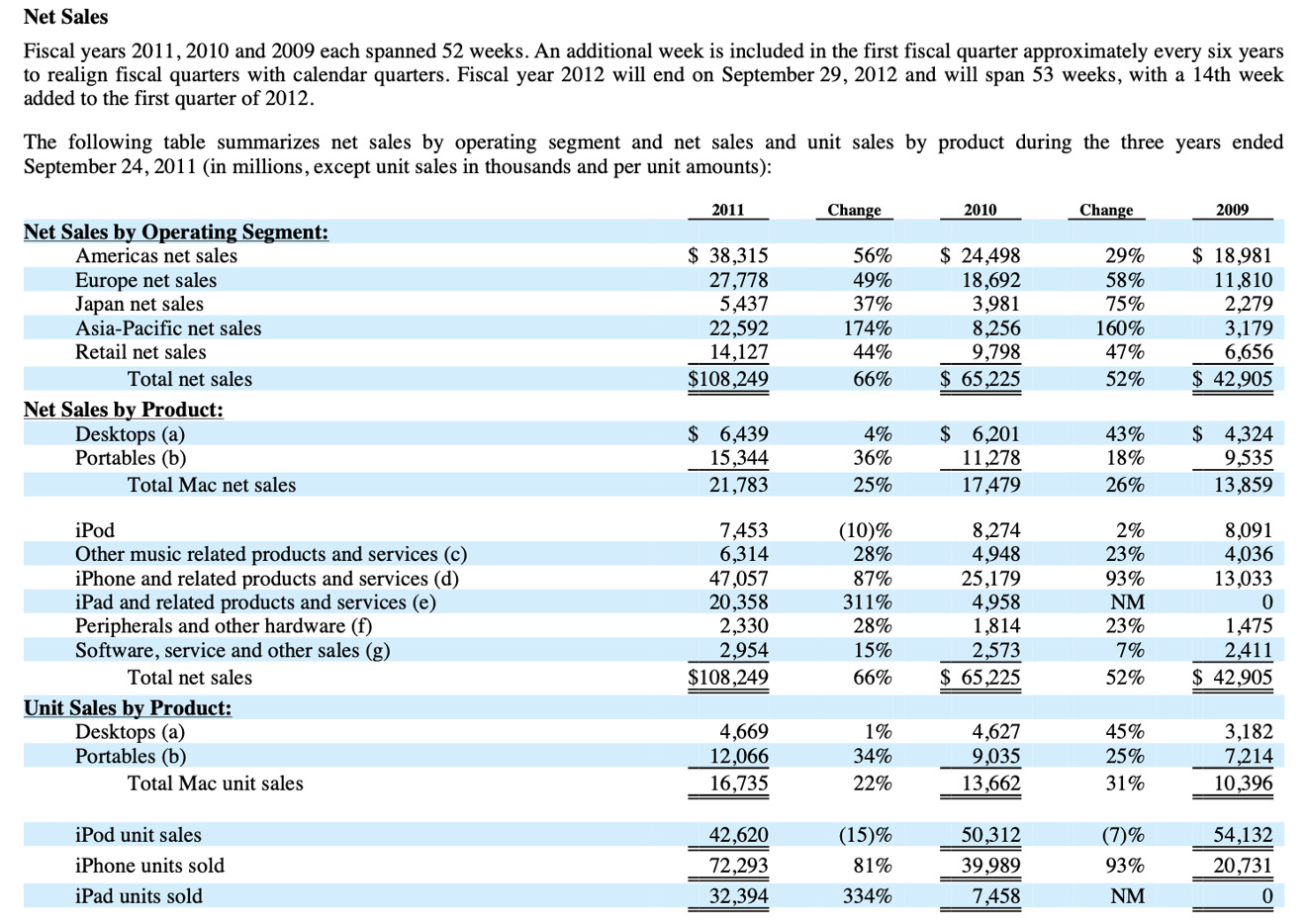

This occurred just as Apple shifted from selling 20M iPhones and 10M Macs in fiscal 2009 to selling 40M iPhones, 13.6M Macs, and 7.5M iPads in 2010. Apple doubled itself, both as both a phone maker and a computer maker, in one year— and most of that new growth was powered by one new chip.

Apple's new A4-related unit sales within 2010 were larger than its entire Mac product line powered by Intel chips. And while Intel's chips were far more powerful and valuable, Apple's A4 was powering device revenues in its first year roughly on par with its $17M Mac business.

Ten years later, Apple still hasn't moved its Macs from Intel's x86 chips to a custom architecture. That would require developing a variety of state-of-the-art silicon scaling from an economical desktop CPU to one for power-efficient notebooks, high-performance notebooks, and high-end workstations, all to power a market opportunity of around 20M units annually while incurring the risk of failure and of falling behind Intel while losing all the benefits of sharing x86 economies of scale.

Apple's Macs also depend on an ecosystem of software that would have to be ported. On its mobile devices, Apple had avoided that problem by launching the iPhone and then iPad as an entirely new platform that made no pretense of running existing third-party Mac software. Apple ported its own apps, including Safari, Mail, and iTunes to ARM, and could then leverage its eventual installed base to create a new ecosystem of apps for iOS.

There was also one existing Mac model Apple could port to ARM: Apple TV. It was originally implemented in 2007 as a limited Intel Mac with an Nvidia CPU. It wasn't really capable of running any third-party Mac software. At the end of 2010, Apple released a new iOS-based Apple TV using an A4 chip, enabling it to shave the price from $299 to $99.

Migrating Apple TV to an iOS-based ARM device was a no-brainer. There had been essentially no significant market for Apple's $300 TV box "hobby," while at $99 Apple TV turned into a billion-dollar annual business when including the iTunes media it helped to sell.

Apple TV could tag along in the wake of the critical mass of new mobile devices Apple sold in 2010, which represented a +25M unit opportunity, all using effectively the same SoC design. If Apple could sustain that growth, it could keep investing in new generations of the A4 and easily pay for the very expensive work of custom silicon design.

In fact, there was no choice. Apple had to invest in new generations of A4 long before the chip even became available and could prove itself in device sales. This required massive foresight and vision, along with incredible confidence that its huge upfront investments would pay off. Most remarkably, Apple had never done this before.

Samsung's motive: conservatively copy what works

Across the same year, Samsung used a codeveloped version of effectively the same chip under its Hummingbird name, later rebranded as Exynos 3, in its Galaxy clones of iPhone and iPad, the Nexus S it built for Google, and it also provided it to new Chinese Android maker Meizu.

Samsung's entire smartphone business in 2010 was less than 25M units in total; the company claimed shipments of 10M Galaxy S phones in 2010. Nexus S, which Samsung was making for Google to sell under its own brand, was lavished with attention but it did not sell in commercially significant numbers. That meant that despite having effectively the same chip as Apple, Samsung was making far less effective use of it.

Samsung was already globally positioned as an established phone maker. It viewed Apple as both an extremely valuable partner uniquely capable of sustainably buying up incredible amounts of its RAM and other components, but also as an emerging new threat in phones. Samsung's own Omnia Windows Mobile and Symbian smartphones had both just been crushed by iPhone.

Samsung's strategy aimed to take ideas from Apple that were attracting customers. It wasn't betting the company on a bold new vision. It was seeking to protect its existing business from further erosion by Apple. That helps to explain why Samsung didn't design an aggressive pipeline of new silicon in parallel with Apple. It expected to beat Apple at its own game and then return to its former comfortable position as a smartphone leader.

Samsung's increasingly bold copies of iPhone and iPad raised the prospect that Apple was once again going to be forced to compete against a copy of its own work, reliving the history of the 1990s when Microsoft appropriated every facet of the Macintosh in Windows, while benefitting from economies of scale driven by Intel's x86 chips.

To avoid that fate in the 2010s, Apple set out to develop a future of custom mobile silicon that could give its own products an edge against Samsung. It then executed that strategy as if its entire future was on the line— because it was.

After A4: a coherent Apple strategy in silicon

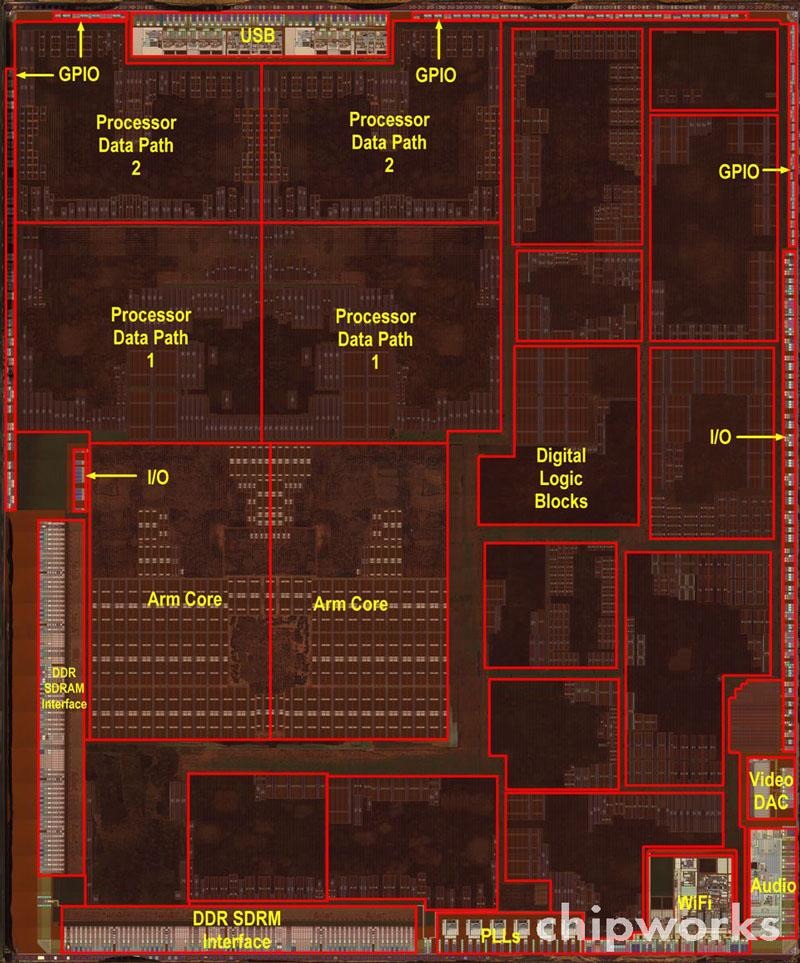

After 2010, it was clear that Apple and Samsung were pursuing dramatically different silicon strategies. At the start of the next year, Apple launched iPad 2 powered by a new dual-core A5 with dual-core PowerVR SGX543 graphics.

While the media had been largely skeptical about iPad's prospects when it first appeared, Apple had confidently developed successive generations of silicon technology that enabled it to deliver a much more powerful version within a year. Part of that confidence clearly came from massive volumes of iPhone 4 sales that would share its chip.

Steve Jobs noted during his introduction of iPad 2 that Apple was the first company to ship a dual-core tablet in volume, and emphasized that A5 delivered twice the CPU power and that its new GPU was up to 9 times faster, while running at the same power consumption of A4. No other phone maker had any plans to deliver that kind of jump in graphics performance for their phones.

Additionally, phone and tablet makers licensing Android faced obstacles that complicated the task of adding dramatic new features such as FaceTime. They could either develop their own unique features that only worked on their models, or wait for Google to deliver an Android-wide feature that dictated the technology they would have to support, while not adding any unique value to their offerings.

Later that spring, Apple also released a new version of iPhone 4 for Verizon's CDMA 3G network. It was assumed Apple would have to replace its A4 with Qualcomm's Snapdragon to work on Verizon, but Apple instead swapped out its Infineon GSM Baseband Processor with a Qualcomm CDMA modem, still paired with its same A4 Application Processor. That move, largely invisible to third-party developers, greatly simplified the architecture of Apple's iOS devices while maximizing the economies of scale Apple was building for its A-series chips.

Apple had already enjoyed a huge surge of iPhone 4 sales with AT&T, and now it was selling another huge batch of the same phone running the same A4 for subscribers tied to Verizon and other CDMA carriers globally. Apple's first original chip design was already a huge success, but there was already a second-generation in play.

Apple subsequently used the iPad's A5 in the iPhone 4S. The new A5 chip also included a new Image Signal Processor for camera intelligence and face detection, and Audience EarSmart noise cancelation hardware to enhance voice recognition, supporting Apple's new Siri feature that was used to launch iPhone 4S. Siri wasn't supported on iPad 2, but the fact that both devices shared the same chip contributed to economies of scale that lowered Apple's production costs.

Some media observers were puzzled at why Apple was shipping A5 devices with just 512MB of RAM, at a time when Android licensees were packing on 1GB or more. While it was popular to claim that Apple's hardware engineering was simply stingy, a better answer was that its software engineering was far superior, resulting in less need for RAM and the luxury of getting by with less. That not only made it cheaper to build, but also helped to sustain battery life because RAM installed in the device required power whether it was in use or not.

That year, Microsoft's Windows lead Steven Sinofsky noted that "a key engineering tenet of Windows 8" involved efforts "to significantly reduce the overall runtime memory requirements of the core system."

While Apple remained quiet on the subject, Sinofsky cited Microsoft's Performance team as detailing that "minimizing memory usage on low-power platforms can prolong battery life," adding that "in any PC, RAM is constantly consuming power. If an OS uses a lot of memory, it can force device manufacturers to include more physical RAM. The more RAM you have on board, the more power it uses, the less battery life you get. Having additional RAM on a tablet device can, in some instances, shave days off the amount of time the tablet can sit on your coffee table looking off but staying fresh and up to date."

Bloggers often liked to draw attention to the fact that Android and Windows mobile devices had more RAM, without any understanding of why this could contribute to lower battery life and less efficient software, yet over time this became obvious.

Apple was rapidly developing two totally different products using the same silicon engine in 2011, effectively subsidizing specialized features for iPhone and iPad at the same time using a processor architecture designed to cover multiple bases. iPhone sales for the fiscal year nearly doubled to 72M, and iPad units quadrupled to more than 32M.

At the same time, Apple could also reuse the A5 to ship lower-priced new tiers of products the next year: a third-generation Apple TV, fifth-generation iPod touch, and a new iPad mini. Apple was investing in a rocketing trajectory of new silicon chips but also wringing every last drop of value from the work it created.

Samsung's wild fragmentation

Samsung wasn't able to use or sell a version of Apple's A5. Instead, it subsequently released its own new Exynos 4, which claimed only a 30% increase in CPU and 50% increase in GPU power over the previous Hummingbird.

With the apparent loss of its access to Intrinsity's optimizations, it was easy to see why Samsung couldn't keep up with the A5's CPU. But its much more dramatic shortfall in graphics capabilities came from Samsung's choice to use basic ARM Mali graphics rather than licensing the same PowerVR GPU Apple was using.

Samsung used its Exynos 4 chip in some models of its Galaxy SII flagship smartphone, but it also sold versions of that phone using Qualcomm's Snapdragon S3 with Adreno graphics, some with a Broadcom/VideoCore chip, as well as selling a version using TI's OMAP 4, which did use PowerVR graphics.

Similarly, Samsung's 2011 update to its original Galaxy Tab also used its Exynos 4. But that same year the company also joined Google in releasing multiple new Android 3.0 Honeycomb tablets, and those models used Nvidia's Tegra 2, following the reference design Google had dictated for its new tablet platform. Later in the year Samsung also released a version of its Galaxy SII phone with a Tegra 2 chip as well.

Complicating the rollout of Honeycomb Android tablets was the fact that Google had initially announced plans to enter the netbook market with Chrome OS in 2009, with the intent of getting the first Chromebooks to market by the middle of 2010.

That confident plan to take over the once-booming netbook category— and perhaps disrupt the market for conventional notebooks like Apple's MacBook— was completely thrown for a loop by Apple's launch of the original iPad. Google had to postpone the launch of Chrome OS netbooks to the end of 2010 and then again to the middle of 2011.

So Google was now floating two mobile computing platforms at once: Android tablets and Chromebooks. Samsung dutifully followed with a little bit of both, rushing out the first generation of Chrome OS netbooks with Intel Atom chips in parallel with its own rebel Galaxy Tab and new Honeycomb tablets. Apple had one product serving that market.

If that weren't enough, Samsung delivered a Windows 7 tablet also using an Intel Atom processor. Samsung's bizarre, scattershot strategy in SoCs was also reflected in operating systems, where it continued to ship Android, Bada, and Windows Phone handsets alongside its Chromebooks and TouchWiz, Honeycomb and Windows 7 tablets, waiting to see what might stick where.

What Samsung ultimately determined was that customers wanted to buy products that looked and worked like Apple's. It even documented its thinking in internal memos that were later used as evidence in Apple's patent infringement lawsuits.

The Linux-based Bada and Windows Phone lost favor at Samsung largely because Android was enabling a closer approximation of Apple's work. Samsung stated a preference to sell its own Bada platform or to work with Microsoft rather than the far less experienced Google. But there wasn't a demand for handsets that weren't closely copying iPhone.

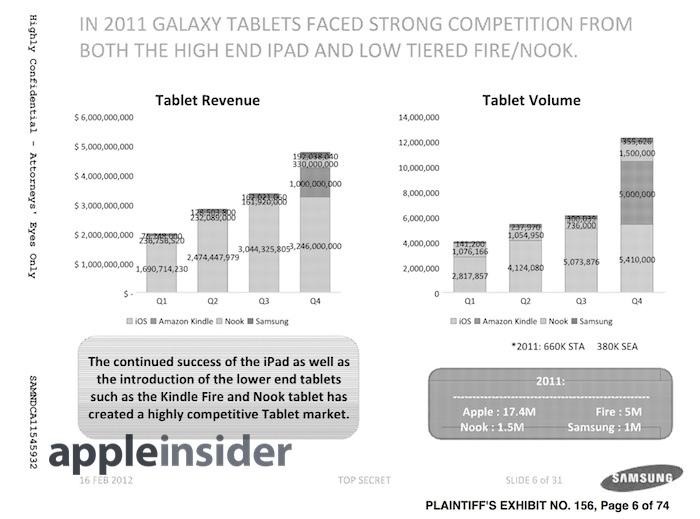

Just within 2011, Samsung delivered multiple versions of 7, 7.7, 8.9 and 10.1-inch tablets, even before attracting any significant installed base of tablet users. Samsung's terrible tablet strategy resulted in equally terrible sales. A "top secret" Samsung document from February 2012 (below) detailed total 2011 U.S. Galaxy Tab sales had only reached around 1 million, contrasted with Apple's 17.4 million iPads, 5 million Kindle Fire by Amazon, and 1.5 million B&N Nook sales in the same region.

That document also made it obvious that the "quite smooth" two million Galaxy Tabs that Samsung was "estimated" to have sold by Strategy Analytics in just the final quarter of 2010— causing a supposed crash in Apple iPad "market share" purportedly at the hands of 7 inch Android tablets— was also completely false.

An emerging media narrative that "Android is winning," based on estimated unit sales that were often simply made up, resulted in a comfortable detachment from reality that enabled Android licensees to continue to pursue strategies that were clearly not working, with the blessing of media observers who refused to critically examine claims from vendors or from marketing groups offering free data to propagate as part of their efforts in "influencing consumer behavior and buying preferences."

iPad wasn't expected to survive

Rather than predicting that Apple's investments in mobile silicon and its tightly managed strategies were setting it up to own the tablet market, the tech media nearly unanimously assumed in 2011 that Google's Android Honeycomb partners would quickly take over Apple's iPad business, in part because of the marketing line that their Android tablets were capable of running Adobe Flash.

In reality, first-generation Honeycomb tablets barely even worked at all, because Google's software wasn't finished and its licensees' hardware had been rushed to market. They were also priced higher than iPad.

Honeycomb turned out to be Google's third major flop after Google TV and Android@Home— fourth if you count Chromebooks— but media critics continued to give the company the benefit of the doubt every year across the last decade as it has rolled out a series of initiatives that have failed as regularly as Microsoft's parade of CES catastrophes in the decade prior. And there is a common thread: both companies relied upon a sea of hardware partners who were themselves not very good at knowing how to introduce successful products.

In parallel with Honeycomb, there were also still expectations that RIM's new Blackberry PlayBook might have some impact based on the company's established base of business customers, or that HP might be able to wield its position as a leading PC maker to establish sales of its upcoming TouchPad. HP had just acquired Palm to obtain webOS in order to give it an alternative to Microsoft's perpetually failing Windows Tablet PC platform.

Jobs didn't expect them to survive

After its first year of sales, iPad was finally becoming acknowledged as a success. However, that success was largely seen as a short term aberration. As 2011 approached, analysts asked Jobs about the supposed "avalanche of tablets poised to enter the market." He answered that there were really "only a handful of credible entrants," but noted that "they use 7-inch screens," which he said "isn't sufficient to create great tablet apps."

Jobs stated "we think the 7 inch tablets will be dead on arrival, and manufacturers will realize they're too small and abandon them next year. They'll then increase the size, abandoning the customers and developers who bought into the smaller format."

It ended up taking more than a year for many makers to give up on 7-inch tablets— Google kept trying to sell them until the end of 2014— but Jobs' anticipation of what would be successful in tablets ended up being presciently correct.

Having a clear, confident, strategic vision allowed Apple to make long term plans, which included developing custom silicon optimized specifically to competently deliver that vision. The chasm between Apple's strategic focus and the scattershot, seemingly random efforts by Google and its licensees led by Samsung would continue to grow, as the next segment will examine.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

William Gallagher and Mike Wuerthele

William Gallagher and Mike Wuerthele

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic