Each day, it seems, brings a bewildering flood of news stories: impeachment hearings, the mess in Syria, another mass shooting, corporate malfeasance, the details of each development quickly surpassed by some new outrage powered by algorithm. In a recent BuzzFeed News piece called “The 2010s Have Broken Our Sense of Time,” Katherine Miller writes, “Life had run on a certain rhythm of time and logic, and then at a hundred different entry points, that rhythm and that logic shifted a little, sped up, slowed down, or disappeared, until you could barely remember what time it was.”

This unrelenting drumbeat leaves many people feeling as though their heads are going to explode. But that feeling—of cascading content literally occupying more space in your brain than is available—isn’t so new. The same sentiment was behind a largely forgotten TV character: Max Headroom.

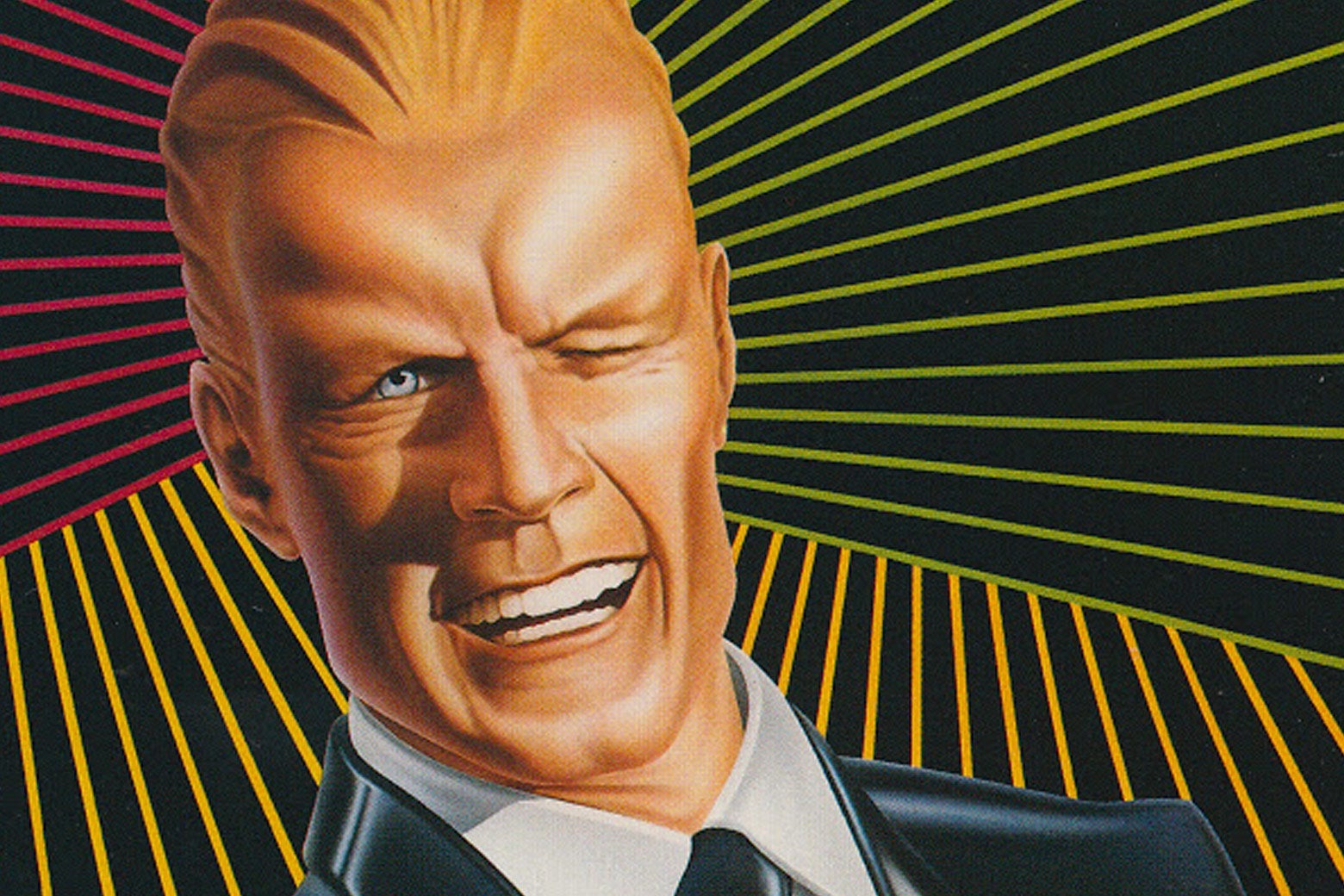

Max Headroom was an animatronic TV icon in the 1980s, a sort of computer-generated, wise-cracking talking head and pitchman. He was an early avatar of the knowing, cynical, and irony-laden sensibility that dominates the media landscape today. Eventually, Headroom’s creators conjured up a weird 1985 TV movie, Max Headroom: Twenty Minutes Into the Future, to backfill the origin story. It eventually became a TV show, broadcast in the U.S. from 1987–88, and it was a wacky one. In a dystopian future, the world is dominated by media conglomerates. Execs meet behind closed doors to discuss how best to manipulate the dupes and rubes who consume what advertisers are selling. A distracted, alienated, and largely powerless citizenry has been consigned to mindless consumption of whatever is on their screens.

And those screens are sometimes literally killing them. In the TV pilot an enterprising journalist, Edison Carter, stumbles on a dark secret. Channel 23, where he works, has developed something called the blipvert, which compresses 30 seconds of commercial content into three seconds before anyone has the chance to change the channel. There’s one small problem: The blipverts can cause people to spontaneously combust from having too much information packed into their heads. Eventually, network honchos hire two hit men to kill Carter. While trying to evade them, he is knocked out of commission when his motorcycle careens through a movable garage arm, with the words “Maximum Headroom” on it. Hence, he becomes the half-revived, half-computerized gadfly, Max Headroom.

The show was a stark and depressing portrayal of loneliness, captured in the blipvert victims’ relationships with their television screens. It imagined people completely alienated from one another, their only connection to the outside world mediated by television conglomerates. Even Carter, in the pilot episode, is an egotistical celebrity journalist content to help Network 23 convert eyeballs into ad dollars. Indeed, when he discovers the blipvert’s effects, he is more excited by his journalistic scoop than horrified by the monstrous crime.

Worries over the potential of technology to isolate and enervate citizens long predate Max Headroom, to be sure. But the show anticipated in some striking ways our growing anxieties about both the political power of contemporary media platforms and their capacity to disorient and disarm us (in some ways, emphasizing themes that Mr. Robot has so expertly explored).

Those longer-term developments have run headlong into a presidency whose agenda seems to be set as much by President Donald Trump’s early morning Twitter rants as anything else. His tweets ensure a constant careening from one plot line to the next as knowing observers have to come think of the day’s news feed. Trumpism, in this context, seems premised on the weaponization of information overload—call it the blipvert presidency.

Since the beginning of Trump’s term in office, members of the resistance have been admonishing people not to “get distracted” and to stay focused on Trump’s core transgressions. In other words, we are exhorted to stay vigilant in fighting that unrelenting cascade of misinformation. But maybe those exhortations are based on an unreasonable set of expectations about the carrying capacity of our brains. Maybe sometimes we do need to tune out, to seek out at least some distraction and give ourselves room to check out of the sheer madness and ceaseless torrent of bad faith emanating from the White House.

The term of art these days in basketball for navigating the rigors of a long NBA season is load management: the idea that star players need to schedule regular days off, even if they’re not injured, to save their energy for when it matters most, the postseason. Some version of that is perhaps called for here. There are limits to what most people can take in before they feel like their heads are going to explode.

It’s not that people should check out completely. Staying informed, involved, and engaged is critical for holding the powerful accountable. But the response to every fresh outrage need not be to stare at it harder and longer.

Over the years, cultural critics, including on Slate, have appreciated Max Headroom as a dystopian tale of the depredations of commercialism and the ways in which media conglomerates have concocted a reality suited to their own interests. In 2019, the profound threat we face is that the political system itself is under siege by a concerted effort to obliterate the wall between truth and fiction. The goal of this war on our institutions and our brains is to weaken both. In place of the blipvert as a sinister conduit for commercial projects, we face a firehose of disinformation meant to pave the way for the ugliest politics imaginable.

Despite the real threats—to democracy, to our individual psyches, and everything in between—of information overload, we are not yet in the world of Max Headroom. Yes, the big tech monopolies represent a serious collective problem, but unlike the corporations of Max Headroom’s world, they’re clearly not on the same page about every major issue. For instance, Twitter recently announced that it will ban all political advertising in 2020, while Facebook will not consider doing so. This matters because while our screen-saturated world is an irreversible reality, there’s no single entity—not even Facebook—that can turn off the information spigot, nor prevent informed and motivated Americans from the critical work of democracy defense. Indeed, in some ways we’re living in a golden age of activism and concerted collective action.

Perhaps vigilance doesn’t have to mean vacuuming up every detail about each new scandal. Overconsumption can be self-defeating. We don’t have to follow every twist and turn of every preposterous offense. In fact, doing so can disorient and demotivate us. Instead, we should commit ourselves to working with those organizations and networks that are tackling the enormous challenges of our day. So, next time you feel guilty because you need a night off from Rachel Maddow or your Twitter feed, maybe it’s OK, even restorative, to give yourself a break. Maybe watch an old episode of Max Headroom instead.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.