This essay accompanies the Evil List, Slate’s poll of experts on the most worrisome companies in tech.

The techlash has arrived, and I am here for it. While the Big Tech companies have truly earned their reputations as bullies, tax cheats, bad employers, and havens for men credibly accused of sexual harassment and abuse, many of my compatriots in the pitchfork-and-torch crowd are curiously forgiving of one of the most egregious offenders: Apple, purveyor of beautiful crystal prisons.

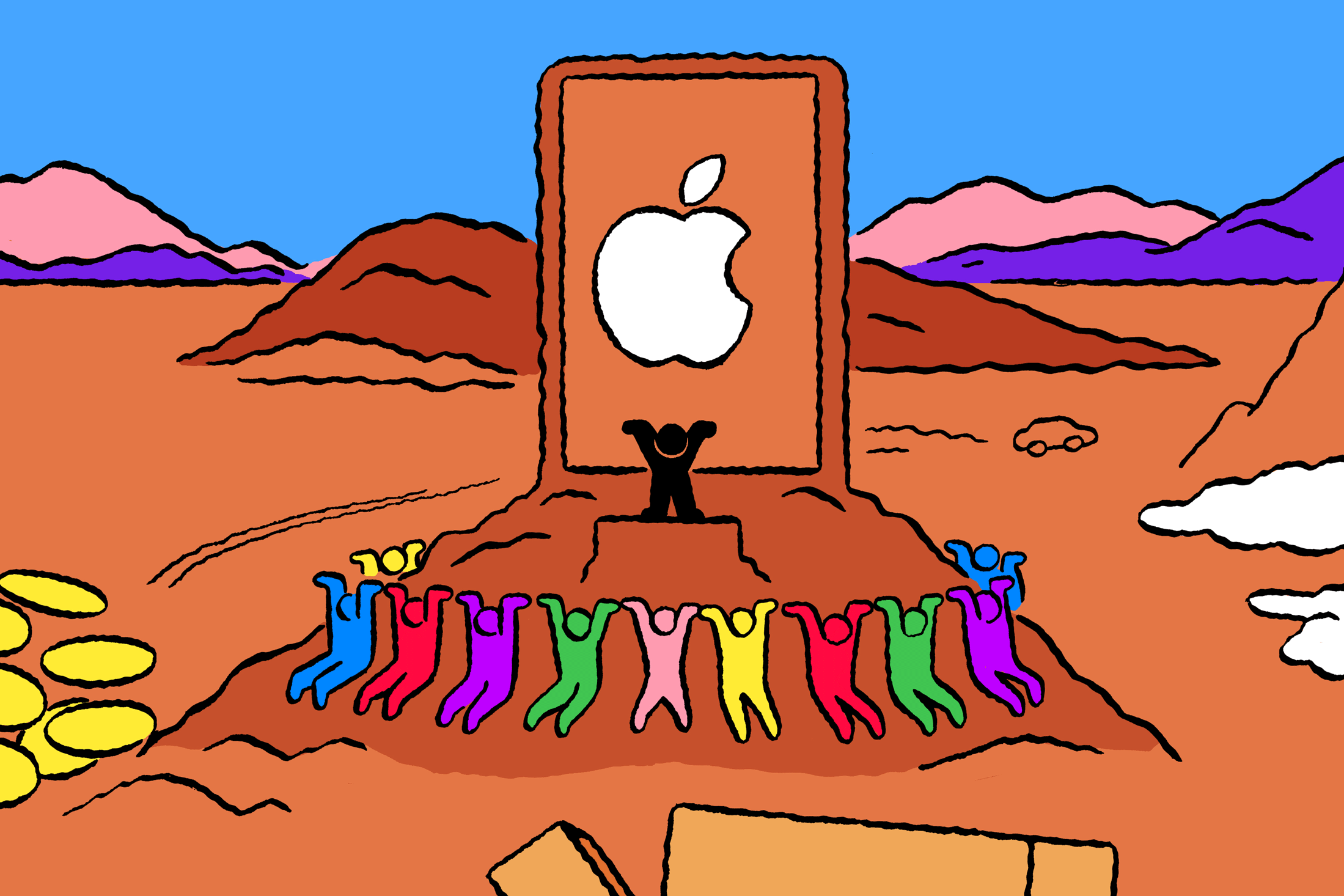

This overall exemption from scrutiny—Slate’s Evil List, in which the company ranks at No. 6, counts as the rare corrective to the conventional wisdom—is nothing new. Apple’s unironic “Cult of Mac” has long been an off-the-balance-sheet major asset for the company, which has managed the seemingly impossible trick of getting its customers to feel like an oppressed minority over their decision to spend money on products made by one of the most profitable companies on Earth. Those products, and the company’s suite of services, treat these customers as adversaries, using a mix of code and law to ensure that they arrange their affairs to Apple shareholders’ benefit.

Apple’s alpha and omega is control: The App Store is designed to ensure Apple gets to decide who provides code to Apple customers, and the company has used this power to block apps on capricious and political grounds, from a dictionary (it had dirty words) to an app that told you whenever a U.S. drone strike killed a civilian to an app used by Hong Kong protesters to evade the city-state’s police forces during pro-democracy demonstrations.

But the most important reason to control apps is to get a bigger cut—a 30 percent cut that Apple takes out of every software developer’s hide (don’t worry, the developers recoup by charging you more). Unlike rival mobile app store Google Play, Apple’s App Store is the only (legal) game in town on its devices. In this, the law is on Apple’s side. Thanks to Section 1201 of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (which bans bypassing “copyright access controls”), if you provide a tool for Apple products to use rival app stores, that’s a potential felony punishable by a five-year prison sentence and a $500,000 fine (for a first offense).

In recent years, Apple has extended this closed approach beyond its operating systems and into its physical devices as well, building phones that attempt to detect third-party parts or repairs by independent service depots. These devices refuse to work if they determine that Apple customers have had the temerity to use suppliers and service centers of their own choosing, rather than Apple’s official service depots.

It’s not surprising that last January, Apple CEO Tim Cook warned his shareholders that Apple’s future profits were seriously endangered by Apple customers electing to use their devices for longer, getting them repaired rather than replacing them. That also explains why Apple led the manufacturer coalitions that defeated 20 state Right to Repair bills in 2018.

Despite all this, Apple gets a pass from its adherents, who rationalize away the company’s behavior, arguing that device owners don’t mind being forced to get their apps, parts, and service from Apple. Obviously, if that were true, Apple wouldn’t have to use any kind of technical countermeasures to prevent people from accessing third-party app stores, parts, and service. The people who want the freedom to make their own choices about their Apple devices are by definition Apple customers. It’s not like Samsung customers are the ones who are taking iPhones to independent repair shops.

Apple is often held apart from the other tech giants because of its public embrace of privacy. The company has indeed taken some admirable stances, like its refusal of the FBI’s demand to weaken its encryption after the 2015 San Bernardino terrorist shooting, and more recently its denial of attorney general Bill Barr’s request that it unlock the iPhones of the Pensacola naval base shooter. But Apple’s arm lock on its users makes it an attractive target for any government that wants to spy on its citizens, and Apple’s resolve isn’t always as strong as it is when the FBI comes knocking.

In 2017, the Chinese government banned the distribution of virtual private networks—which are supposed to keep web browsing private and secure—insisting that they be replaced with VPNs with known back doors to allow the Chinese state to capture and analyze VPN traffic. That summer, Apple removed all working VPNs from its App Store in China. Concerned about this move, Senators Ted Cruz and Patrick Leahy sent a letter to Apple saying the company “may be enabling the Chinese government’s censorship and surveillance of the Internet.” A year later, we learned that consequences of Chinese state surveillance was anything but abstract. In May 2018, the Associated Press first reported on concentration camps for Uighurs, Kazakhs, and other predominantly Muslim ethnic minorities in Xinjiang province, and credible estimates put the total number of incarcerated people at 1 million. Rather than push back against China’s demands, Apple made a change to its app platform that potentially made the rounding up of these prisoners easier. The fact that this was not the commercial surveillance that has earned Facebook and Google scrutiny is hardly relevant. Apple’s decision not to mine its users’ behavior for advertising purposes is no comfort when it so easily folds to the demands of a surveillance state for nonadvertising purposes.

Nor is the fact that Apple would struggle to keep its supply chain intact if it were kicked out of China any excuse: It’s not like the country’s dismal human rights record was any secret when Apple made it central to its operations (and of course this is just as true of every other manufacturer that has made its business dependent on keeping Beijing’s politburo happy).

There’s a touchstone of the techlash: “If you’re not paying for the product, you’re the product.” But the reality is that monopolists are endlessly inventing ways of extracting rents from their customers and suppliers. In fact, the saying works even outside the free-for-data model of Facebook and Google. When it comes to Apple, even if you’re paying for the product, you’re still the product: sold to app programmers as a captive market, or gouged on parts and service by official Apple depots.

And Apple’s techniques have proliferated: The control-through-software model has metastasized into every category of device, from “smart” light sockets that require manufacturer-approved bulbs to “smart” Nerf guns that require manufacturer-approved foam darts. Apple’s control over service has caught the attention of the likes of John Deere, which will cheerfully sell farmers tractors for hundreds of thousands of dollars and then tell the U.S. Copyright Office that they don’t own the tractors, merely license them, and that is why they can’t expect to repair their agricultural equipment, as farmers have done since the days when every barn had a workshop and a small smithy attached to it.

None of this is to let Google, Facebook, Oracle, or Microsoft off the hook. These companies are all monopolists that have spent the young century engaged in abusive and anti-competitive conduct, from buying up their nascent competitors (Apple bought 20 to 25 companies in the first six months of 2019) to merging with their largest competitors to cornering vertical markets, then abusing suppliers, retailers, and customers with verve not seen since the days of Carnegie and Rockefeller. Google isn’t your friend, and neither is Facebook, nor Twitter, nor Airbnb.

And neither is Apple.