Why Apple's supply chain is prepared for China's coronavirus

The outbreak of the coronavirus, now infecting tens of thousands of people, has stoked fears that Apple would be dramatically affected both from lost sales in its China and interruptions to its component supply chain. However, while Apple has its work cut out for it it also has a uniquely proficient operations team to manage crisis events, one that has been challenged before.

Apple's retail closures

As China scrambles to contain the outbreak of the highly infectious strain, media bloggers working to erect fear, uncertainty, and doubt about Apple's prospects have sensationalized the greatest imaginable potential impacts on Apple. That naturally includes Apple's product sales in China, where its brick and mortar retail stores have been closed for a few days following the Lunar New Year holiday period out of "an abundance of caution."

Never mind that store closures— and full city shutdowns in some cases— aren't unique to Apple. Apple has the fewest stores in China of any of the major handset manufacturers. Apple's few dozen landmark retail stores in China exist to establish the company as a permanent, enduring brand capable of supplying customer service for its products well into the future.

Most rival domestic phone resellers in China operate vast numbers of kiosks designed to sell their cheap Androids largely via promotional pricing. The greatest impact of broad retail store closures will fall on brands such as Huawei, Oppo, Vivo, and Xiaomi, who all strive to make razor-thin margins on vast unit sales of commodity devices. Their businesses are contingent on massive sales volumes shipped out at minimal cost — and Apple's are not.

Buyers looking for iPhones, or a Mac, or AirPods or anything else from Apple aren't shopping by price. They also aren't even very inconvenienced to make their immediate purchases over the next several days directly from Apple's online store. With the assurance that before they need assistance, or support, or a training session, Chinese Apple Stores will eventually open up again.

It might sound scary and dramatic to breathlessly report that "Apple Stores are closed. Still, a temporary closure is far better than stoking any fears that one might come in contact with the virus while assembled in one of the few, large, jam-packed stores that Apple operates within China's urban areas.

It would be irresponsible for Apple to prematurely open its stores and risk spreading the contagion among its customers and employees.

The reports of factory death have been greatly exaggerated

Fear-mongers have also targeted the potential impacts that travel bans, quarantines, and business closures within China might have on Apple's ability to build its products for global audiences, because much of its components and assembly are centered in China.

On Saturday, Japan's Nikkei Business Daily even cited "four people familiar with the matter" to claim that "public health experts" in China had determined a "high risk of coronavirus infection" at Foxconn facilities where Apple assembles its products.

Yet that report was immediately refuted by local authorities in Shenzhen. Officials stated in social media channels that the report was untrue. It also noted that inspections were still ongoing but that factories were expected to resume production "in a timely matter," and that none of the factory operators have requested any "need to resume production earlier (than the local governments' recommendations)."

As with Apple's retail stores, an "abundance of caution" in closing factories for a few extra days until proper procedures are in place to monitor and handle any new outbreak are a sign of competence and responsibility. It would be far more disastrous if Apple and its partners were rushing to restart production, risking a much greater operational interruption in the future.

Apple has long been taking the lead in employee safety, worker rights, and environmental protections, a luxurious moral stance it can afford as a very profitable company. Yet its competitors in China have long had a poor reputation in safeguarding their employees or even monitoring factory safety. Which Android makers can afford to take elaborate steps to keep their factories and their workers safe and productive when they are already barely profitable at peak production?

A persistently negative media bias that's consistently wrong

The Nikkei has previously issued alarmist reports from people supposedly "familiar" with Apple's production, its supply chain partners, and the demand among consumers for its products. These have regularly proven to be false. They were not minor errors. The Nikkei specifically claimed to know via "channel checks" that iPhone X had suffered "disappointing holiday season sales" in early 2018, immediately before it was revealed that iPhone X was the world's most popular smartphone throughout its debut quarter.

The Nikkei has also regularly claimed nearly every January that Apple was supposedly "slashing" its phone orders, portending a massive decline in sales that always failed to materialize. Conversely, the Nikkei and its supply chain checks and its various "people familiar with situations" have never revealed the emergence of a surprise hit Apple product in advance, despite there having been so many.

The Nikkei hasn't been alone in promoting false stories with sloppy attribution, with an alarming bias for reporting false negatives specifically targeting Apple— as opposed to occasionally just getting its facts wrong in various ways. America's Bloomberg and Wall Street Journal have also joined Nikkei in promoting incorrect or misleading reports of "supply chain production cuts" as evidence that iPhones were about to suffer from a sudden lack of interest among buyers who were belatedly discovering that Androids were cheap.

Journalists who have no clue about how well a massive hit product is selling in Japan, Europe, and the United States during its peak holiday quarter— or what rumored supply chain numbers might mean about Apple's overall production numbers and the demand for its products— are clearly not going to be able to understand what impacts might be associated with supply chain interruptions occurring during Apple's slowest season of production following both the Western holidays and China's Lunar New Year festivities.

It is fortuitous that the coronavirus outbreak hit just before the massive migration of travelers occurred in China. The timing means that people expecting to spend money traveling to their hometowns for the holiday season were less likely to be put in close contact with other carriers of a highly infectious disease, and they ended up with extra money to spend on things like Apple's hardware or Services.

Of all of the industries impacted by transportation and business closures, Apple's luxury devices are not the ones to be worries about.

Apple's global supply chain was built to weather crisis

When China was hit by SARS back in 2002, Apple was barely just entering the iPod business. Yet SARS prepared the world to consider the impact of global epidemics. After five years of learning to build iPods by the tens of millions, Apple shifted to rapidly becoming a major phone maker, fully derailing Microsoft's global partnerships for Windows Mobile phones, as well as brutally sidelining major phone makers including Palm, Nokia, Blackberry and Motorola.

In 2010, Apple introduced iPad along with its own custom A4 silicon powering 50 million devices, requiring global coordination between its U.S. chip design, Korean chip fabrication, and Chinese assembly. Every year following, Apple dramatically increased its appetite for components while selling incredible numbers of premium-priced, luxury tech devices that maxed out production capacity across multiple major factories of Foxconn, Compal, Pegatron, and Wistron.

Apple has adeptly shifted production between factory operators and set up parallel sources for a wide variety of its components, creating a global operations beast that is so complex, it is virtually impossible for anyone outside to make any meaningful assumptions about what a specific shift in production means. That's been repeatedly proven in the terrible track records of analysts trying to interpret isolated bits of data leaking from the supply chain.

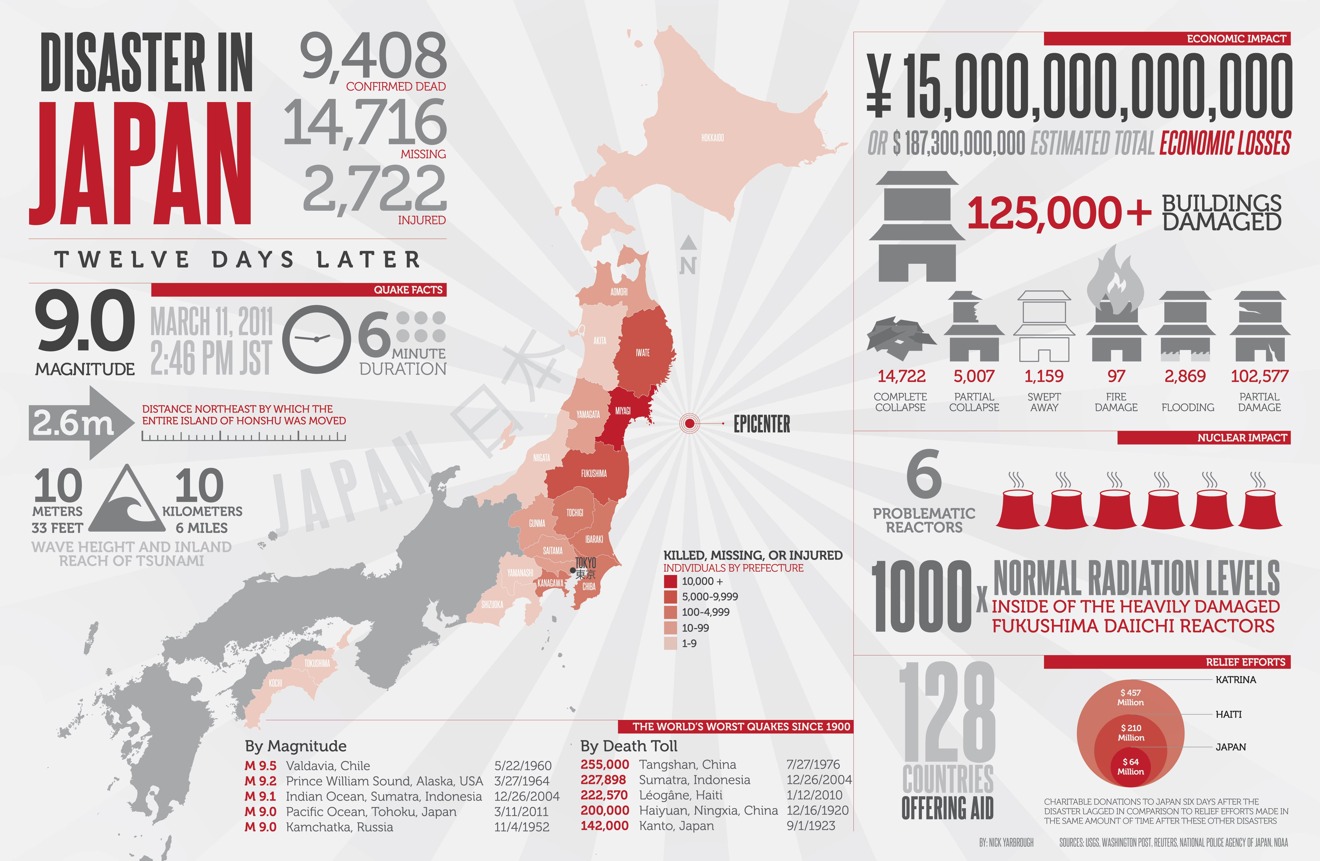

But all that mysterious complexity serves a critically important function. It makes Apple resilient to crisis. In March 2011, when iPad 2 was brand new, Tohoku, Japan, was hit by a disastrous combination of earthquake and tsunami that was widely reported to be a major problem for Apple in both components and production.

When Apple officially addressed the issue in April during its earnings call with analysts, its executives stated that the economic effects of the disaster in Japan "pales in comparison to the human impact," and effectively dismissed the crisis in reporting that Apple did not expect the situation to materially affect the company. Executives revealed that it had employees working "around the clock on contingency plans."

The crisis in Japan occurred during peak demand for the new iPad 2, described at the time as "staggering." Apple was reportedly sourcing the new iPad's NAND flash, DRAM, compass, touchscreen overlay glass, connectors, and batteries all from Japanese suppliers, who were collectively reported to be "significantly damaged" in the disaster. Yet Apple was able to dance around serious production issues and meet the demand for record shipments of its tablet.

That was nearly ten years ago, when Apple's annual revenues were at $108 billion compared to 2019's $260 billion. Apple had barely established the iPad business, and its leadership was struggling to deal with Steve Jobs' increasingly serious illness, a new competitive threat posed by Google's Android, Microsoft threatening to use Windows to drive mobile enterprise buyers away from iOS, and Samsung shifting from its role as a primary components partner to a copycat rival seeking to run it out of business.

Those accessory threats are all virtually gone today. Apple has spent the last decade refining and strengthening its supply chain to build far higher volumes of devices with minimal need for inventory. In 2018, when a computer virus hit Apple's singular chip fab TSMC and shut down its production lines for the new A12, it was fretted about in the news for a cycle but had no observable impact on Apple or its sales.

Apple is now so self-sufficiently powerful that it can simply decide to shut down the use of massive aluminum smelters that produced virgin material for its MacBooks, opting instead to develop its own blend of recycled aluminum to radically reduce the carbon footprint of its entire global operations. That's a luxuriously privileged position to be sitting.

Apple has incredible cash reserves and massive sway over global component operations. It literally shifts markets around as it launches new products. If there's any need to be concerned about who will be affected by any global event— including the most recent coronavirus in China— it's certainly not Apple that anyone needs to voice concerns about.

Apple's weaker, less profitable competitors, on the other hand, will clearly be more adversely affected.

And even if there were some temporary impact on iPhone unit sales that could be attributed to the coronavirus, we've already seen that Apple can turn around the market in China. It just did. A year ago, journalists were all nodding in agreement with each other that certainly— this time— buyers were now hip to cheap Huawei Androids and were never going to buy an expensive Apple iPhone again, in part due to pure patriotism for domestic goods.

Yet, for some reason, that patriotism didn't impact Chinese sales of Macs, iPads, and Apple Watch, even though Huawei and other domestic brands rip off all of Apple's other products and offer their versions for far cheaper. Instead, in a direct rebuke to the arrogantly bantered around "common wisdom" that Huawei was eating up iPhone sales, what happened was that iPhone buyers were simply delaying a minor number of their purchases due to economic uncertainty.

When sales resumed during Apple's present fiscal year, they were incentivized by pricing and financing that Apple could easily afford to offer. As a result, iPhone sales bounced back, driving Apple to record revenues and profits.

There was no shift to Huawei and back. Journalists had made up a plausible idea and insisted it was fact.

At the same time, the iPhone sales Apple achieved this quarter were not merely comparable to the "water under the bridge" commodity units shipped by various Android licensees in China. Apple is building a clear ecosystem of users who also buy its other products and services. That's evident in the fact that, as reported last week in Apple earnings call, "three-quarters of the customers buying a Mac in China are new, and nearly two-thirds of the customers buying iPad are new," and that overall, 75% of Apple Watch buyers are new.

That's a massive wave of new premium-class purchases— users intentionally locking themselves within the walls of Apple's castle moat— among the increasingly affluent urban consumers of China, representing a vast new middle class that continues to emerge from poverty in China. Just like Americans, they aspire to have nice things, not just cheap things.

That interest in affordable luxury is on clear display in China, although we recommend waiting for coronavirus to be fully contained before going to see for yourself.

Apple's operational excellence is vilified rather than appreciated

A major factor in Apple's ability to profitably build and deliver premium, high-end technology products with well-performing software and then sell its devices to global audiences in vast volumes despite the presence of cheaper alternatives is its focus on global operations.

Note that neither Google nor Microsoft bothered to build any sort of sophisticated global operations in their hardware efforts. Their miserable commercial results with Pixel and Surface reflect that.

Media bloggers and even serious-sounding analysts have often appeared to be utterly blind to this reality. Recognizing the value of Apple's operational excellence would also contradict their recent narratives that insisted that Apple was growing far too concerned with boring Operations and should instead be focusing its efforts on delightful Design whimsy.

This romantic delusion of a former, glorious Apple back when it was mostly building translucent plastic laptops for school kids appears to have clouded pundits' understanding of what has made Apple wildly successful as a global operation over the last decade in particular. It wasn't bright, bubbly plastics, or a fancy folding mechanism. It was operational excellence on a global scale.

Just last summer, Tripp Mickle of the Wall Street Journal wrote about how terrible it was that Apple had supposedly shifted from being Steve Jobs' lovable design-focused boutique of Jony Ive creations into being a brutally grotesque global enterprise commanded by Tim Cook only to generate money. The rest of the Wall Street Journal doesn't spend so much ink vilifying capitalism, but Mickle has a special beat. Even though he has very little understanding of how Apple works, a headline that involves the company pretty clearly attracts clicks and sells ads— the brutal way that paper pays its staff.

Mickle dramatically lamented that the departure of Jony Ive "cements the triumph of operations over design at Apple, a fundamental shift from a business-driven by hardware wizardry to one focused on maintaining profit margins and leveraging Apple's past hardware success to sell software and services."

That was written in 2019, nearly a decade after Cook— who had been Apple's operations chief since the late 1990s— was unanimously appointed to continue running Apple as its chief executive officer after Jobs' passing in 2011.

Apple's dramatic turnaround under Jobs, which began with the acquisition of Jobs' NeXT in 1997, also coincided with the identical period of Cook running Apple's global operations. That's because one of the Jobs' first priorities to get Apple back on track involved Cook's recruitment from Compaq to streamline the company's beleaguered operations that were bleeding cash. It was suffering production shortages of valuable notebooks in demand, and huge rotting inventories of products that weren't selling.

It's not merely a coincidence that Apple rebounded alongside the appearance of Cook and his development of a world-class operational structure for the company.

Even with Jobs at the helm, NeXT had possessed its futuristic OS software and development tools for nearly a decade without being able to effectively create any hit products that it could sell with the kind of success Jobs later found at Apple.

During that same decade, Apple also struggled to sell products— several of which involved great, innovative technology— despite having Ive and a variety of other very competent industrial designers on board. It even had an iconically designed clamshell netbook with a translucent plastic shell and a stylus, all the things that modern pundits think Apple should be offering, featuring a novel, attractive design by Ive. It didn't sell well, nor did it make any money, in part due to Apple's operational problems.

Apple's chief executive Tim Cook built the very thing that turned the company around under the leadership of Jobs, and prepared the company for its decade long global expansion under Cook's tenure as CEO. That vast, complex, sophisticated operational structure was built to keep Apple competitive and resilient to competitive threats and external crises, including even the unprecedented temporary shutdown of a massive superpower by a virus.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

Sponsored Content

Sponsored Content