Apple is making headlines with rumors of a record-sized bond sale.

According to reports, Cupertino is likely taking advantage of historically dirt-cheap interest rates on corporate debt by raising about $17 billion from a series of six types of bond papers.

It's not the largest non-bank bond sale in history, but it does rank near the top. Automaker General Motors raised $17.5 billion in bond financing a decade ago, for example. Then again, GM's financing arm, then known as GMAC, sort of made a bank out of the car builder. Pharma giants Abbott Laboratories and Roche Holdings also issued $14.7 billion and $16 billion in bond debt fairly recently. Record-level or not, Apple's sale certainly ranks right up there with the big boys.

Why Apple needs more cash now

You might wonder why one of the world's richest companies is raising debt right now. There's no single factor forcing Apple's hand here, but there is a perfect storm of ingredients that add up to a hunger for new debt.

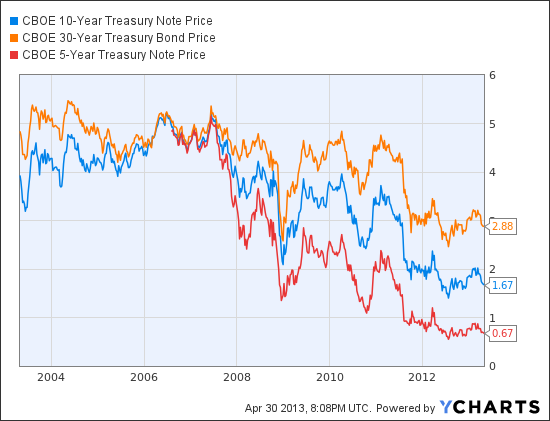

First, interest levels are vanishingly low at the moment. Bond interest rates are typically attached to the rates of US Treasury Notes, and every flavor of these important papers are trading near 10-year lows. In short, it's rarely this cheap and easy to get your hands on fresh loans.

Second, Apple just announced that it plans to return $100 billion directly to shareholders over the next three years. That's more than double the previous plan, which called for $45 billion in dividend payments and share buybacks by the end of 2015. Even Scrooge McDuck would have a hard time finding that much spare change in his couch pillows, which explains why Apple is resorting to some financial engineering to fund the expanded plan.

Which brings us directly to the third point: Much of Apple's $145 billion in cash and investments come from sales outside the US and it's locked down in bank accounts on foreign shores. Simply closing those bulging Swiss, Irish, and Cayman bank accounts would make Apple's cash subject to so-called repatriation taxes. As much as one-third of that cache would go to Uncle Sam. The company only has about $45 billion in dollar-denominated All-American cash on hand to power that generous dividend and buyback program.

Better, then, to pick up cheap debt that's backed by the international cash reserves and use that as fuel for the shareholder-friendly programs. Let the foreign reserves percolate until the government tries another repatriation tax holiday, like the Homeland Investment Act of 2004. Or perhaps until Apple finds a use for its foreign cash, like a large acquisition.

Lastly, Apple is no longer the high-growth wunderkind of Wall Street that it used to be. Like Microsoft did 10 years ago, Cupertino has started catering to value and dividend investors. That demographic loves companies that hand out cash to shareholders, and debt is a perfectly acceptable source of financing for such policies. Look at the big banks as an example. Bank of America manages a $610 billion cash reserve but also sits on $618 billion in debt. That's just how these guys roll, making a mint on the spread between the returns on their own investments and the interest they offer to customers. Apple follows a proven path here.

$145 billion in the bank and still no perfect credit rating

So Apple's bond sale comes from the confluence of several key events. The company isn't even alone in exploring low-interest bond sales right now. Microsoft posted a $1.9 billion sale last week. Redmond's bonds garnered top-notch AAA credit ratings from both Moody's and Standard & Poor's, just edging out Apple's AA+ S&P grade and Aa1 from Moody's.

Triple-A businesses outside the banking world include Microsoft, Exxon Mobil, Automatic Data Processing, and Johnson & Johnson. All of these are proven cash machines just like Apple, but the devil is in the details. Moody's pinned Apple's imperfect rating on working in "a highly volatile industry" and needing to raise as much as $50 billion in debt over the next five or six years. "Just based on that, it didn't smell like a triple-A," a Moody's analyst told Bloomberg.

The third major credit ratings agency, Fitch, went further and suggested that Apple could be at risk of a spectacular implosion similar to those of Sony, Nokia, and Motorola Mobility. "Each has historically had a dominant market position and strong financial metrics, only to falter over a relatively short period of time," Fitch analysts wrote in a recent Apple report. Cupertino simply doesn't have the long-term contracts that a true top-notch credit rating requires.

What's next?

The next few years will be critical to Apple's long-term health. The company is making the transition from high growth to stable income—and change is never easy.

Tim Cook and company may set their sights too high and make promises they can't keep. Cutting down an announced buyback-and-dividend plan is hazardous to your share price, and diving too deeply into debt can damage your financial health. So Apple would be smart to set the bar low.

Shoot too low, and you'll look like you don't believe in your own future. That's another surefire way to scare away investors, not to mention trend-sensitive consumers.

It's a tricky balancing act. We're sure that Apple will be around ten years from now, but the coming two or three years will map out the path to a healthy, mature business—or a company on the ropes.

reader comments

103