At first blush, it looked serious: a Web link to a known source of malware buried deep inside of a highly rated app that has been available for months in Apple's iOS App Store. For years, antivirus programs have recognized the China-based address—x.asom.cn—as a supplier of malicious code targeting Windows users. Were the people behind the operation expanding their campaign to snare iPhone and iPad users?

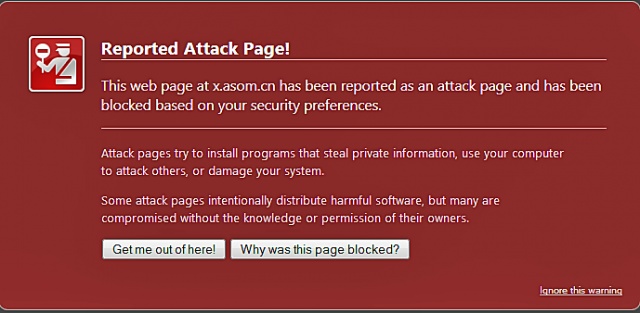

Although Macworld writer Lex Friedman said the link was likely harmless, I wasn't so sure. As he pointed out, an iOS app from antivirus provider Bitdefender warned that the Simply Find It app, last updated in October, contained malware classified as Trojan.JS.iframe.BKD. Even more suspicious, Google's safe browsing service was causing the Firefox and Chrome browsers to block attempts to visit the address on the grounds that it had been reported as an attack page. "Some attack pages intentionally distribute harmful software, but many are compromised without the knowledge or permission of their owners," Google's advisory warned as recently as Thursday.

So, what was the link, embedded in an HTML tag known as an iframe, doing in an MP3 file included with the game? Who put it there? And, most importantly, was it infecting people who installed Simply Find It on their iOS devices?

I spoke to researchers specializing in smartphone security at Bitdefender and Lookout Security. After examining the app, they determined the app poses no risk to iOS users. That's because the exploits hosted in the past at x.asom.cn (don't visit this site unless you know what you're doing) are designed to load malicious code inside existing HTML files. While it has the potential to do damage in certain Web-browsing settings, its presence on the storage device of a computer or smartphone is, in fact, harmless.

"While the code itself is malicious placed in the right context (i.e. in an HTML document), it has no side effect when injected into the wrong file," Bogdan Botezatu, senior e-threat analyst at Bitdefender, told me. "There is no known mechanism to date to exploit this behavior on users' machines, and the file definitely does not pose any threat to the iOS users."

Boteazatu speculated that the iframe was accidentally included in metadata embedded in the MP3 file, most likely by an infected computer that stored the sound file at some point.

Tim Wyatt, who is director of security engineering at Lookout, agreed that the rogue link was likely the result of accidental cross-contamination.

"We definitely agree with the assessment that there's no apparent threat here," he wrote in an e-mail. "It's likely a case of a developer unwittingly including a file that was swept up in the compromise of another system without being aware of the injected content."

The theory makes as much sense as anything I can think of, and as Wyatt went on to note, it wouldn't be the first time malicious code was inadvertently embedded into a smartphone app. In February, Lookout researcher Tim Strazzere documented the existence of links inside an Android app that also pointed to sites known to be malicious. He speculated they were added by someone compiling the code with an infected computer. The app almost certainly wasn't a threat to most end users, although it might have been a problem for smartphone running a custom version of Android.

The issue of cross contamination shines a light on the app vetting process performed by both Apple and Google, which both companies have so far kept fairly opaque. If AV companies can detect malicious links in iOS and Android apps, it seems reasonable that the companies running the App Store and Google Play can, too. While malicious links have so far turned out to be harmless, hackers by definition find ways to make hardware and software behave in new and unexpected ways. Next time, we might not be so lucky.

reader comments

47