NEW YORK—In a Manhattan courtroom, Apple and the Department of Justice gave their opening statements in the e-book price-fixing case United States of America v. Apple Inc. The government presented a position based on interpretations of direct quotes from relevant documents where Apple allegedly discussed ways to raise e-book prices not only on its own platform, but across the industry. Apple defended itself by saying that it acted in no one’s business interests but its own, that its employees were misquoted and their statements taken out of context, and the government is “trying to reverse engineer a conspiracy from market effect.”

The government has pursued a price-fixing case against Apple since April 2012, accusing Apple of leading five of the six largest book publishers to raise e-book prices in concert across the market. The government thinks Apple used two tools to accomplish this: an agency model (publishers set e-book prices and Apple gets a cut) and a “most favored nation” (MFN) clause in the publishers’ contracts, where Apple is allowed to set its prices as low as any other entity selling the same product.

The “ringleader of conspiracy”

In his opening statement Lawrence Buterman, a trial attorney Department of Justice and co-lead of its legal team in the case, stood calmly behind the podium and spoke with absolute certainty regarding Apple’s actions. Buterman cited Apple as a “facilitator,” “go-between,” and “conduit,” with Apple’s senior vice president of Internet software and services Eddy Cue as the “chief ringleader of conspiracy” and of the alleged “collective” that ultimately appeared to shift e-book prices away from the $9.99 price point that Amazon had so commonly used—up to prices of $12.99 and $14.99.

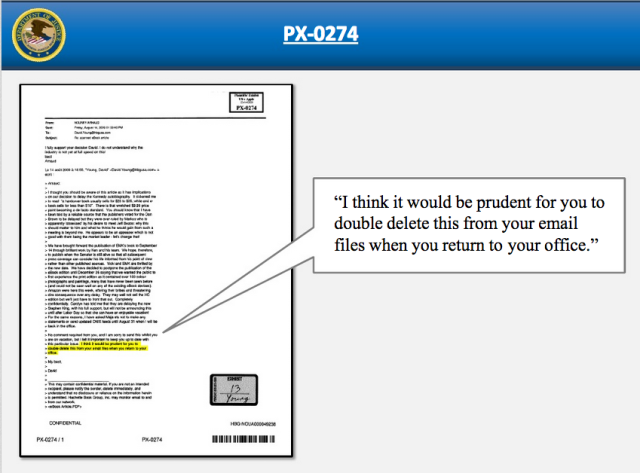

Buterman pointed to several e-mails from Apple and publishing company executives as evidence. The DOJ said the e-mails indicate that Apple not only sought to establish itself in the e-book market, but conspired with the publishers who were unhappy with Amazon's $9.99 price point and the perception of e-book value that came with it to raise prices across the market.

Apple’s joint use of the agency model and MFN clause, combined with the cooperation of five of the biggest publishers in the US, gave those publishers the motivation they needed to force Amazon into the agency model and away from the $9.99 price point, according to the DOJ. “It was about solving their collective goals,” Ryan said.

The publishers had been looking for a way to raise e-book prices for some time, Buterman said, but were unsuccessful in working together. They “needed more ammunition… that ammunition came in the form of Apple.” Buterman cited an early meeting between HarperCollins and Apple where HarperCollins said it was looking to move to an agency model as a way to “fix Amazon pricing.” Later, an e-mail from Eddy Cue to Steve Jobs noted that Apple’s use of the agency model would “solve the Amazon issue.”

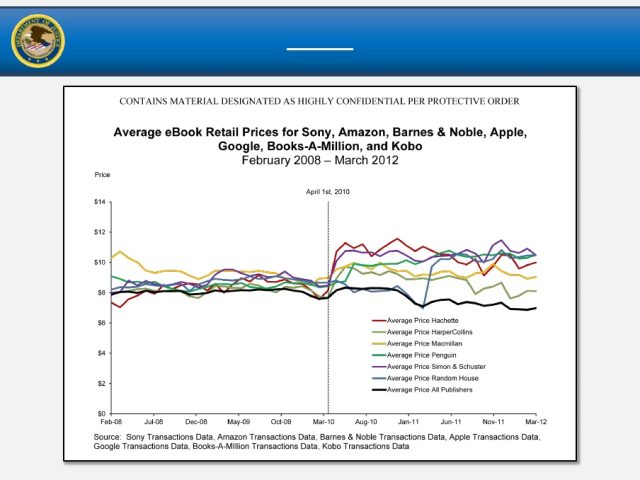

Buterman displayed in a PowerPoint a graph of the average prices of e-books from each of the six largest publishers, including Random House, which did not sign with Apple’s iBookstore. When the iBookstore launched in 2010, the prices of these books on Amazon, Google, Barnes and Noble, and Sony stores all took a sudden jump upward.

Some of the DOJ’s case hinges on an interview that Jobs had with the Wall Street Journal’s Walt Mossberg following the iPad’s launch. Jobs assured Mossberg that the iBookstore’s prices would be “the same” as on other e-book stores, despite the higher-than-normal $14.99 price shown during the presentation.

“Publishers were not happy” with Jobs for saying that, Buterman said. Not that Jobs stated the prices would be lower, but that Jobs “admitted” the plan to raise e-book prices, in the DOJ’s interpretation. Carolyn Reidy, CEO of Simon & Schuster, wrote in an e-mail about that Jobs interview snippet, “I can’t believe that Jobs made the statement below. Incredibly stupid.” Earlier in the day, the DOJ released its PowerPoint presentation for public consumption.

A “bizarre” application of antitrust law

Apple’s lead attorney, Orin Snyder, opened by stating that “Apple has been waiting for this day for a long time.” Snyder paced in a triangle—squared up to the podium, off to the side fully facing the judge, and back and away from the podium nearer to his legal team—as he dismissed the government’s evidence as “out of context, misquoted” and cited from “introductory meetings and brainstorming sessions” wherein a supposedly naive Eddy Cue was merely spitballing solutions for Apple to reign in publishers for the nascent iBookstore.

Snyder called the case a “bizarre” application of antitrust laws, since Apple was an unestablished player trying to enter a market overwhelmingly dominated nine-to-one in sales by Amazon. As Snyder pounded the table over United States District Judge Denise Cote’s preliminary statements that she was leaning the government’s way, Cote reminded Snyder that it was her “tentative view.” But Judge Cole also reminded him, as he stated Apple should be applauded for its actions and how it has changed the way the world consumes media, that the suit does not hinge on “whether [she likes] Apple or anyone likes Apple.”

Snyder called the idea that Jobs would admit to the alleged price-fixing either in his WSJ interview or in his own biography “farfetched.” He also stated that Apple told publishers “we do not care” when it came to how they squared their business with Amazon, and that the MFN clause gave them “the ability to be indifferent” to other players’ deals with the publishers.

Snyder described the difficult negotiations that Apple and the publishers went through to come to agreement. The discussions were “knock-down, drag-out,” and “protracted,” and he argued that the government had oversimplified them to paint a picture of the company and publishers acting together, Snyder said.

Snyder stated that HarperCollins resisted Apple’s MFN to the point where Jobs needed to go over its head to the man in charge of its parent company, Rupert Murdoch. “The largest publisher [Random House] said no,” Snyder said. And Hachette responded to a draft contract saying the MFN clause was a deal breaker, to which Apple responded that was a dealbreaker for it, too.

These disagreements were not the actions of companies aspiring to conspire, argued Snyder. “Apple needed to launch a business, not a conspiracy.” Snyder said “the interests of Apple and publishers were not aligned,” and that the publishers, which the government asserts were working together, “appeared entirely uncoordinated from [Cue’s] point of view.”

But process aside, part of Apple’s defense is that it had a positive effect on the e-books industry. While not directly addressing the graph the DOJ had shown earlier, Snyder said that “every single indicator of health… trended positively” after Apple got involved in the e-book market.

Apple’s defense also cites Amazon’s exploration of the agency model for e-books back in 2009, describing the e-book market as both “not established” and a virtually monopolized one, patting itself on the back for managing not only to enter it with force, but to effect what Apple says were positive changes across the industry.

The trial is set to continue for three weeks, an expedited pace as requested by Apple. Over the next few days, witnesses including Eddy Cue and David Shanks, CEO of Penguin group, will take the stand to testify in the case.

Listing image by 3dom

reader comments

299