On Saturday, Intel officially took the wraps off its first next-generation desktop and laptop CPUs based on the "Haswell" architecture. Absent from that reveal, however, was any mention of the low-power laptop CPUs that will carry Intel's Ultrabook initiative into 2014. Turns out Intel was just saving those particular announcements for Computex proper. Now, we can finally talk about the dual-core parts in the Haswell rollout.

A single low-power Core i5 chip is the only desktop part being announced today. The other 16 CPUs that are being unveiled are all U, Y, and M-series chips aimed straight at mainstream, thin-and-light laptops and tablets (as well as the convertible PCs that Windows 8 has made so common).

We gave a high-level recap of Haswell's features in the original announcement piece, and we won't cover that ground again here: the basic CPU architecture, the changes to the GPUs, and the new 8-series chipsets are the same whether we're talking about dual-core or quad-core Haswell chips. What we'll cover now are changes to the U- and Y-series' power consumption, the kinds of machines that Haswell can fit into that Ivy Bridge had trouble with, and the specific CPUs that are being announced today.

As we said in our last write-up, keep in mind that all of the numbers below come directly from Intel, who will be working hard to present their processors in the best possible light. We'll be examining these performance and power consumption claims more fully when we have production Haswell systems to test with.

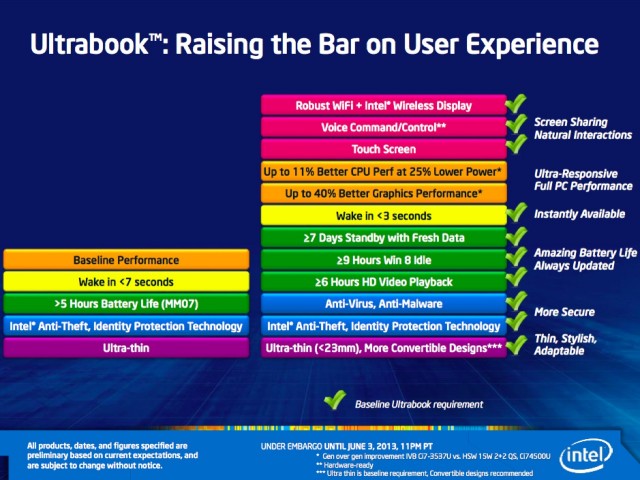

Evolving the Ultrabook

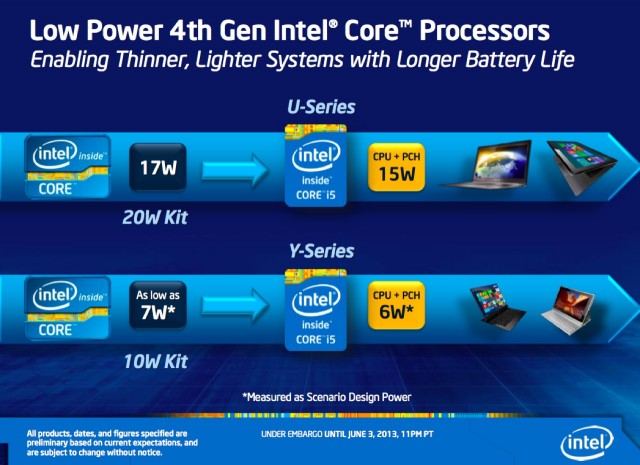

Intel's Ultrabook strategy with Haswell is roughly the same as it was with Ivy Bridge: the majority of the low-power processors will be part of the ultra-low-voltage U-series intended for most laptops and laptop-like convertibles (think the Dell XPS 12 or the Lenovo IdeaPad Yoga). These CPUs will have 15 watt TDPs, down from 17 watts in Sandy and Ivy Bridge.

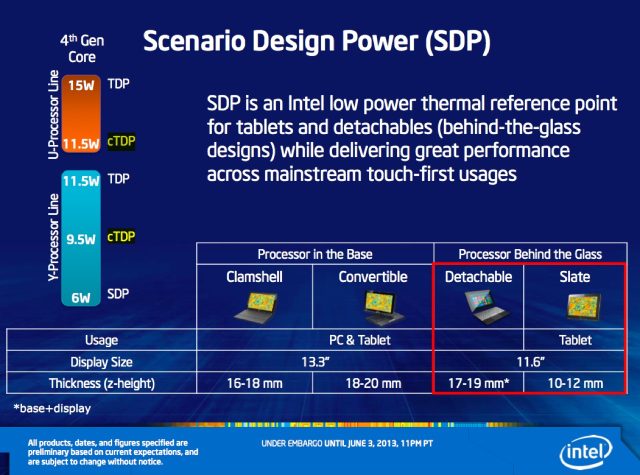

With Haswell, Intel will also be pushing "behind the glass" convertible PCs more emphatically than they could with Ivy Bridge. If you can't guess, these are convertible laptops that store their hardware behind the screen rather than in the base of the laptop, enabling you to take all of your processing power with you if you remove the screen from the keyboard. Designs like this exist today, but many of them are based on slower ARM and Intel Atom processors. Trying to put Ivy Bridge chips "behind the glass" can result in bulky tablets like Acer's Iconia W700 and the hot-running Microsoft Surface Pro.

The Haswell Y-series CPUs are much like the Ivy Bridge-based ones we saw at CES, complete with slightly confusing power envelopes. These CPUs have an 11.5 watt TDP, down from 13 watts in the Ivy Bridge versions. The sticking point is what Intel calls "scenario design power," or SDP. We explore just what SDP means more fully in this article, but the short version is that OEMs can configure the U- and Y-series chips to hit a lower TDP than the 15 and 11.5 watt maximums. This is something OEMs could always do if they really wanted, but beginning with the Y-series chips Intel now validates the CPUs for operation at these lower power levels.

This adjustment comes at the cost of some performance, but it can allow the chips to consume less power and fit into smaller enclosures without requiring Intel to further complicate its already overcomplicated product matrix. The Y-series CPUs have a six watt SDP, down from seven watts in Ivy Bridge and they also have a 9.5 watt "cTDP" between the max TDP value and the SDP value. U-series CPUs also have a cTDP of 11.5 watts, but don't have a validated SDP value.

The advertised power consumption figures for the ultra-low-voltage Haswell chips are a bit more impressive once you consider that the chipset is actually integrated into the same package for these CPUs rather than being a separate chip (as in Ivy Bridge and its predecessors). For instance, the Ivy Bridge U-series chips had a 17 watt TDP, and the chipset itself had a separate TDP of three watts (adding up to a total of 20 watts). The 15 watt TDP figure for the U-series Haswell chips includes the chipset, making for a 25 percent combined reduction in TDP.

Combined with the "active idle" power state, which allows Haswell laptops do more when idle and transition between active and idle states more quickly, Haswell has the potential to enable significantly better battery life for general-usage workloads. We'll need to see some production Haswell laptops before we can put these claims to the test, but on paper they're very promising.

Integrating the chipset into the CPU package also slightly reduces the amount of space on the PCB that the chips take up, leaving more room for batteries, RAM, or other components. Soldered-on memory has become an unfortunate fact of life for many Ultrabooks these days, but at the very least I'd like to see laptops with 4GB of it go by the wayside.

All of this adds up to a set of improvements that don't radically change the Ultrabook form factor, but they may solve some of the problems keeping certain Ivy Bridge Ultrabooks and tablets from being great. Ivy Bridge tablets like the Surface Pro are the strongest case in favor of this argument, but the poor battery life of Acer's original Aspire S7 or Asus' twin-screened Taichi are also good examples. Haswell might not enable radical form-factor changes, but we suspect that several almost-great Ivy Bridge devices will be able to use Haswell to get the boost they need.

reader comments

50