As you may have heard by now, Samsung and Jay-Z have teamed up to offer users of Galaxy S III, S 4, and Note II phones the opportunity to hear his new album, Magna Carta Holy Grail, three whole days before anyone else.

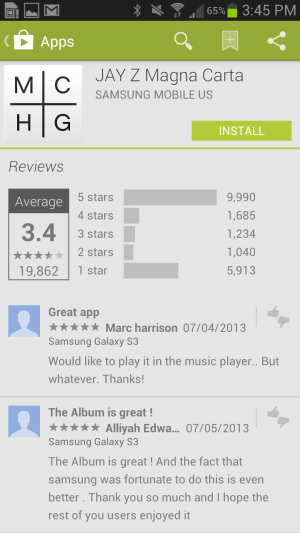

Samsung has its own music store that it could, in theory, use to drop this musical treasure trove into the hands of the Galaxy-toting masses, but the company instead chose to distribute the music through a Google Play app. That's strange enough on its own, but actually installing and using the software is a free master's class in how not to make an app.

Downloading most applications from Google Play prompts a permissions window that you have to click through before the application will install. The best apps don't ask for anything they don't need, and most restrict their requests to things that make sense. Yes, a Web browser will need Internet access. Yes, a photo-editing app will need access to your device's storage. Yes, a map app will need access to your GPS.

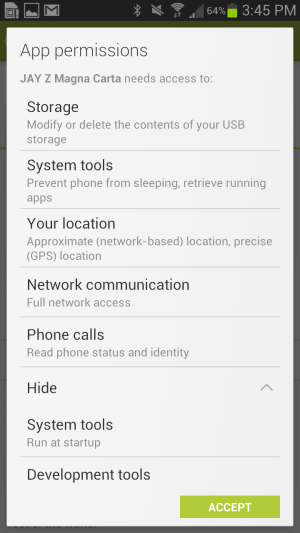

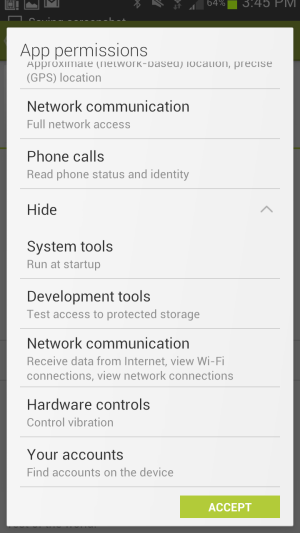

Jay-Z and Samsung's app, on the other hand, is positively PRISM-like in its requests for your information. All told, it asks:

- To modify and delete contents stored on your phone

- To prevent the phone from sleeping and view a list of all running apps

- For your location, via the GPS

- For full network access

- To see who you're talking to on the phone

- To run at startup

- To test access to protected storage

- To control the phone's vibration

- To view accounts set up on the phone

It's not as if the app needs access to everything an Android phone can do, but it's a lot more than you'd expect from an app that exists solely to let you play 16 songs. If CyanogenMod's incognito mode didn't sound appealing before, maybe it will now.

Let's assume that you have no problem handing all of this stuff over to Jay-Z and Samsung. Tap accept and launch the app, agree to the typically wide-ranging and overlong privacy policy, and you'll finally get to listen to your music!

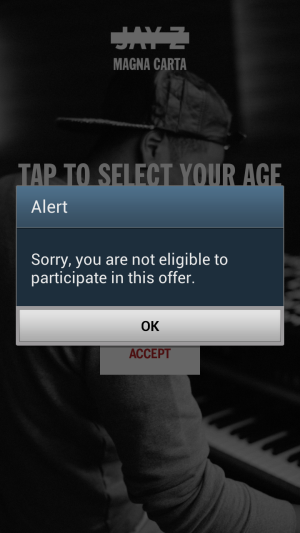

Or, wait. First you need to sign in with either a Facebook or a Twitter account. Then, you need to verify your age. Don't worry, though! If you enter an age that's too young (anything equal to or younger than 13 for the clean version, 18 and up gets you the explicit version) the phone will just tell you that you are "ineligible for this offer" until you enter a sufficiently high number. If you get it wrong, just keep trying!

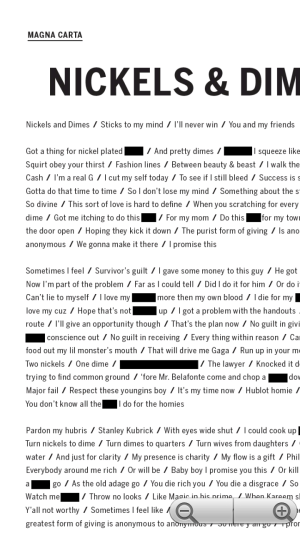

After that you can finally get into the app, download the songs, and watch the preview videos. It's not a particularly attractive app, but it's at least functional. A feature that would have allowed you to send out canned Tweets or Facebook status updates in exchange for song lyrics has apparently been done away with now that the music is available—I could zoom in and out of the poorly-presented PDFs without polluting any of my social feeds.

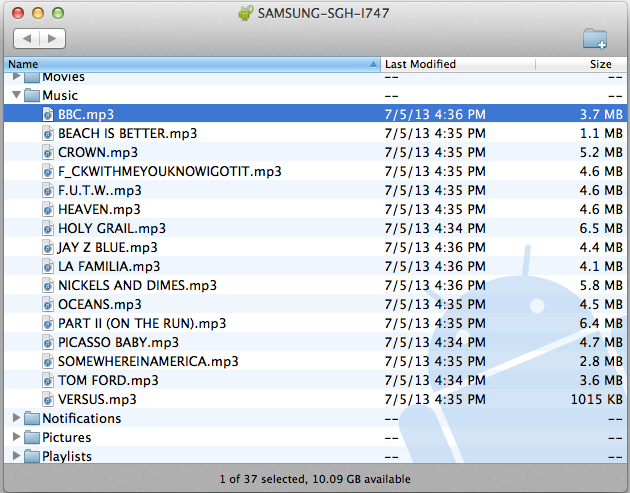

The truly irritating thing is that once you download the songs through the app, it becomes an empty husk that you don't even need anymore. The app just dumps the (completely DRM-free) 160Kbps MP3s in the device's Music folder, where they can be played in the local music player app or copied to a computer via USB. There's nothing keeping you from taking these files and sharing them as you'd like, which is admittedly great for users but a bit mysterious from Samsung and the record label's perspective. We all knew this was a play for user data and social media attention, but you don't have to be so obvious about it.

This app's very existence is vaguely bewildering. The number of permissions it asks for verges on parody. Its (previous) ability to spam up your social feeds is obnoxious. Its presentation is perfunctory at best. It does nothing to protect the songs from downloading and sharing—of course, this would have happened with Samsung's cooperation or not, but if the point was "exclusivity," then somebody missed a memo somewhere.

Samsung probably considers this marketing campaign to be a success on the grounds that we (and the New York Times, among many others) are even talking about it in the first place. And, given that the entire Ars staff spent at least half an hour talking about it this afternoon, they're not wrong. If someone decided to run out and buy a Samsung phone based on this particular app and advertising campaign, though, let's just say we'd be surprised.

Listing image by Andrew Cunningham

reader comments

112