At some level, you'd think that Twitter should have an easier job than most at thwarting spam. While you can get an e-mail address almost anywhere and use that to dispatch junk correspondence through carefully cloaked servers, you can't get a Twitter account without going through Twitter's servers and being counted in the exhaustive analytics the company runs to track what happens on its service.

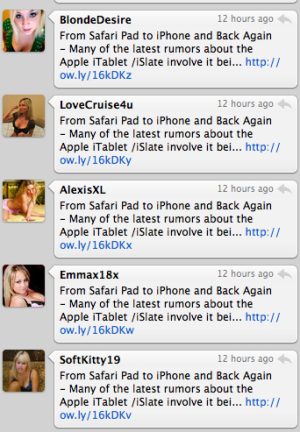

Yet Twitter's more than 200 million active users continue to see obvious fake users in their timelines, all proffering the same dumb come-ons—Weight loss! Make money from home!—as the cretins who have been polluting our inboxes for the last few decades.

A study presented at last week's Usenix Security Symposium in Washington—"Trafficking Fraudulent Accounts: The Role of the Underground Market in Twitter Spam and Abuse"—uncovered some contributing factors to the problem and found potential signs of hope.

The study was written by three researchers at the University of California at Berkeley—Kurt Thomas, Chris Grier, and Vern Paxson—with George Mason University professor Damon McCoy and Twitter software engineer Alek Kolcz. Funding came from the National Science Foundation, the Office of Naval Research, and Microsoft Research.

The researchers set out to analyze the Twitter-spam economy by participating in it. With Twitter's permission, they bought 121,027 phony Twitter accounts from June 2012 to April 2013 at a median cost of four cents each, hoping to study their traits.

None of the sellers wised up to the tactic, even after the release of the study. McCoy told me by e-mail, "This market is open and sellers don't ask their customers any questions." (Twitter PR did not respond to queries.)

The team’s initial findings were all bad. "Merchants thoroughly understand Twitter’s existing defenses against automated registration and as a result can generate thousands of accounts with little disruption in availability or instability in pricing," they wrote.

Those who register bogus accounts can evade Internet Protocol address blacklisting or throttling by routing registrations through tens of thousands of other hosts, many hacked PCs in botnets. They sign up with easily obtained phony Hotmail, Yahoo, and mail.ru e-mail addresses. They crack enough CAPTCHAs to stop them from being an effective block.

But because the people who harvest fake Twitter accounts usually sell them to third parties, disabling accounts that act spammy only hurts the buyers; the actual retailers of fake accounts keep ringing up sales.

Noting that, the authors write that targeting suspicious account-creation behaviors can help identify future sources of Twitter spam.

Risk factors

Without actually using the word "pretweetcrime," they cite such risk factors as using e-mail accounts that can be opened without phone verification (Hotmail figured in just over 60 percent of the fake accounts purchased, with Yahoo in second place at almost 12 percent); common patterns in the randomized user-agent strings, Twitter names and Twitter handles generated by account scammers' scripts; and skipping such common new-user steps as importing contacts.

(Microsoft Senior Product Manager Dharmesh Mehta said in a quote forwarded by a publicist that the company screens new registrations against "an ever-evolving list of fraudulent activity patterns" and may "require additional proofs before taking certain actions to help verify the account.” A Yahoo spokesperson said the company uses "advanced technologies to filter out mass registration abuse.")

The study endorses using these criteria to classify and delete many fake accounts automatically and subject others to additional screening.

For example, the authors observed that many purchased accounts come without credentials for the e-mail address used to open them—which lets merchants re-sell those addresses to others. Requiring dodgy-looking new users to confirm their e-mail addresses a second time would lock them out. The researchers also endorsed phone verification of suspicious Twitter handles.

After building a classifier to flag fake accounts on those criteria, the researchers ran it against "several million" phony ones created by the 27 merchants they had purchased from—and then unplugged 95 percent of the fakes. In a test purchase done right after that sweep, 90 percent of the newly procured accounts had already been suspended.

Two weeks later, however, 46 percent of another round of test purchases remained usable.

In an e-mail conversation after the conference, Grier explained that the classifier had only been run as a batch job, not a continuous process, which let its data grow stale. But the fact that merchants had yet to change their naming conventions—which provided what he saw as the easiest countermeasure for Twitter—offered the promise of catching up quickly.

Thwarting Twitter spam would then become a game of percentages. But that's all you can hope for when battling businesses that employ the "we make it up on volume" predator-satiation strategy of cicadas.

Listing image by dѧvid

reader comments

60