At the annual Game Developers Conference (GDC), the big games industry question that comes up every year is “how.” As in, "How is the game sausage made?" Topics like platforms, engines, and middleware dominate GDC's five days of panels, full of artists and programmers trying to make sense of how to get games running on as many devices and marketplaces as possible.

But in more recent years, the insider conference has locked eyes with another, more uncomfortable question: “who.” More specifically, who comprises the modern game-design demographic? What does that demographic look like?

Before Colleen Macklin, a game design professor at the New School at Parsons, began trying to answer that question during a GDC panel, she queued up some camcorder videos she had filmed during this year’s conference. “I’m going to let this loop as an ambient track during my talk, and you may begin to see some patterns,” she said.

The primary pattern was clumps of white men, gliding up and down escalators or meandering through GDC’s hallways, intersected every so often by a cluster of Asian men, a person of African descent, or a woman.

Despite years of growing GDC advocacy tracks that celebrate more diverse game makers, this demographic breakdown was still present at 2014's show, and it probably surprised nobody in the crowd. But for Macklin and the other diverse game makers and educators in attendance, simply asking “who” wasn’t good enough this year.

“We’re designers!” Macklin said. “We’re talking about systemic issues. Instead of saying how hard it is to create diversity, let’s create prototypes of a welcoming and diversified field. Let’s playtest them.”

The first such call came from the same panel. Titled #1reasontobe, the panel sought to carry the momentum of a 2012 Twitter conversation in which the game industry’s minorities spoke out on why they persevered in spite of hiring and attitude roadblocks. Interestingly, one of its most striking contributors this year confessed to a different attitude.

Her father, a coder at Oracle, made sure his daughters had computer access at a young age, but he also did them one better: “Instead of resigning himself to the fact that a young, black, female protagonist might not come around for many years of gaming, he took the tools at his disposal and made this.” Scott gestured to an image of a 1997 Java-coded game her father made starring his daughter. “At five years old, I knew a black girl could be a character in games.”

Her childhood interest held up, and she now studies beneath game design legend Brenda Romero at UCSC. As a result, her call to action wasn’t for her young peers, but for the veterans who might be on the verge of leaving the profession. “Your calls to action are working,” she said. “But you have to stay. Your knowledge is valuable. We talk about minorities of women in gaming, but women veterans are just as rare. We need to study under the masters to hone our skill.”

“Post-White House, I’ve become an asshole”

Romero herself spoke at GDC’s annual Women in Gaming luncheon earlier the same day, where she was pressed for advice. For the most part, she stuck to gender-neutral tips, including the importance of public speaking, while other luncheon panelists took a more aggressive stance.

Former White House gaming czar Constance Steinkuehler was frank about her hiring perspective: “The game is rigged and weighted against women. If you haven’t hit 40 or had kids, you will find it. So, post-White House, post-tenure, I’ve become an asshole. Now, hell yeah, when I see two equal candidates with the same credentials and same chops, I will hire the girl.”

Xbox Entertainment Studios producer Lydia Antonini took a broader stance on the question of hiring, explaining that her former jobs in Hollywood required “almost a report card” of diversity in any job search, a proactivity that she believes should reach the top levels of games-industry hiring. “That forces you into a new way of thinking about how you hire,” Antonini said. “Now you’re going to LULAC, other organizations, and meeting people; otherwise, you’ll just get the same crowd of applicants every time.”

At the #1reasontobe panel, Double Fine programmer Anna Kipnis spoke to this sentiment, but in a more contained, studio-specific manner: “Up until a month ago, I hadn’t tried to make a game myself, even though I’d had plenty of opportunities,” she said. She described Double Fine’s regular Amnesia Fortnight series, in which staffers pitch ideas for prototypes that are voted on and turned into brief, team-driven projects—an intimidating prospect for someone who had never done more than filled a slot in a larger design team.

Once she got over the fear that her ideas weren’t fleshed out enough, she realized that her pitches were actually ahead of most of her design peers. This year’s Amnesia Fortnight included her pitch, Dear Leader, as a top vote-getter. So she had a message to game studios’ top brass: minorities on a staff can use an extra shove about participation and inclusion. “Encourage everyone to pitch games. Even office managers and IT. Make everyone feel involved in the creative process.”

The New School's Macklin spoke like a designer, understanding that expanding the diversity of an entire industry would require a concentrated playtest. First stop: GDC itself. Such experiments can’t only happen in the “advocacy” set of panels, she insisted, because “if this track is so successful, it will eat itself and be the cause of its own obsolescence. I want to hear design talks from these folks, in addition to their personal experiences.”

She equated designing a new player experience to opening up a speaker application process and compared pre-production efforts for experiments and diversity to having conversations with potential new speakers. “Let new voices speak on their own terms instead of fitting them into whatever takeaway structure already exists. Let’s burn this panel down.”

“Maybe it’s better to be invisible”

Though the day’s conversations were highly proactive—full of high-minded ideas and calls to action—frustration and discontent bubbled up, and deservedly so. Most panelists included either a slide or a reference to nasty, anti-diversity comments, made either online or by real-life encounters. Macklin sighed at men in an industry-insider site's comments section trying to explain away why more women didn’t work at their companies: “The discrimination has to do with their ability to perform the task at hand; programming doesn’t interest many females; gender and sexual preference is an issue, but it’s being overplayed.”

It’s not. Two of my game-industry peers told me they were aggressively spoken to and groped at this year’s GDC by total strangers. No matter how much work, effort, genius, and creativity they put into their work, they still left GDC having to question whether they attended as game designers or as objects at the mercy of the conference’s men.

Still, it wasn’t my place to shout, to be loud, to cry and be angry about the nonsense some of the most brilliant members of the world of game design go through. But it was definitely Deirdra “Squinky” Kiai’s place (Kiai prefers the gender-neutral “they” as a pronoun and will receive that courtesy for the remainder of this article.)

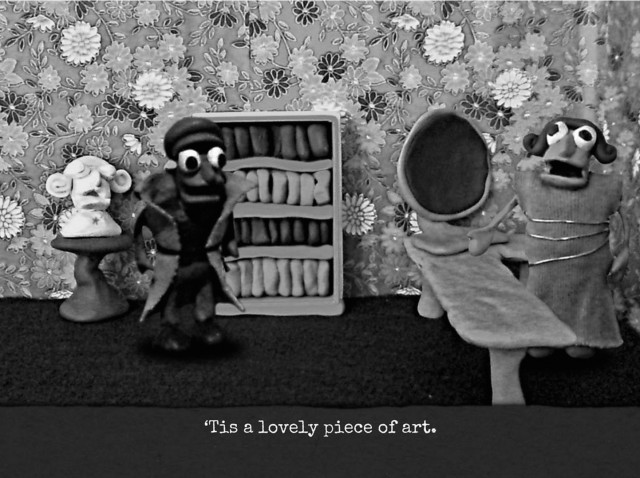

Kiai closed the #1reasontobe panel by thanking the show’s IGF Awards for not rewarding their stellar point-and-click, Claymation adventure game Dominique Pamplemousse in any of its four nominated categories. “The more attention and notoriety I get, the more I wonder when the 4chan trolls are going to get me, like they’ve done to pretty much every single person I like and respect in games,” Kiai said, voice booming louder with every word. “Maybe it’s better to be invisible. I know invisible, and I can live with invisible.”

In spite of computer tinkering since the age of three, releasing an adventure game of their own at 16, and getting an industry job directly after undergraduate school, Kiai fully believed that they were never a proper fit for the games industry. “Games were never meant for people like me. They were always someone else’s story. I couldn’t make games about myself because I didn’t even know who I was. I never saw myself represented anywhere.”

It wasn’t until Kiai found the browser-based RPG Fallen London at the age of 25 that they felt a tinge of inclusion at being allowed to choose “person of mysterious and indistinct gender” as a character option. “I didn’t have to be a defective woman or a defective man. Just myself.” From there, Kiai rode a wave of other game makers defecting from an unsavory games industry to make their own games, and in Kiai’s case, it was one they could pour newfound feelings of identity into.

The takeaway, Kiai said, was that other men and women could create more inclusion in the industry, a larger safe space in which big and small studios increase their diversity, without sweeping any of the anger, frustration, or disappointment under a giant, digital rug.

“Authentic, true, and weird,” Kiai said. “That shouldn’t just be okay, but important.”

reader comments

203