Apple executives never mentioned the words "iCloud security" during the unveiling of the iPhone 6, iPhone 6+, and Apple Watch yesterday, choosing to focus on the sexier features of the upcoming iOS 8 and its connections to Apple's iCloud service. But digital safety is certainly on everyone's mind after the massive iCloud breach that resulted in many celebrity nude photos leaking across the Internet. While the company has promised fixes to both its mobile operating system and cloud storage service in the coming weeks, the perception of Apple's current security feels iffy at best.

In light of one high profile "hack," is it fair to primarily blame Apple's current setup? Is it really that easy to penetrate these defenses?

In the name of security, we did a little testing using family members as guinea pigs. To demonstrate just how much private information on an iPhone can be currently pulled from iCloud and other sources, we enlisted the help of a pair of software tools from Elcomsoft. These tools are essentially professional-level, forensic software used by law enforcement and other organizations to collect data. But to show that an attacker wouldn’t necessarily need that to gain access to phone data, we also used a pair of simpler “hacks,” attacking a family member’s account (again, with permission) by using only an iPhone and iTunes running on a Windows machine.

As things stand right now, a determined attacker will still find plenty of ways to get to iPhone data. They need to gain physical access to the device, or harvest or crack credentials to do so. But there are ways to do this that won't alert the victim. The weakest links are components of the iCloud service.

A quick word on Apple security

The iCloud thefts were likely aided and abetted either by a weakness in iCloud’s authentication for the “Find My iPhone” application interface or by some clever deduction of passwords or security questions based on data about the targets gleaned from public sources (like, for example, Wikipedia). Sadly iCloud backups, because of their nature, often contain data long gone from a phone itself, or at least data that's gone from what the phone user can see onscreen.

Again, Apple has a number of security fixes coming. For example, the new tweaks will alert users by e-mail and push message when there’s an attempt to restore a backup from iCloud to a new device, to change a password, or to connect a new device to an iCloud account. While this may not have prevented the celebrity information swipe entirely, it would have at least alerted those being targeted that their accounts were accessed. In addition to these alerts, Apple will also push harder for users to use two-factor authentication in iOS 8—which will cover access to iCloud from mobile devices.

Apple has done a great deal to improve the security of the iPhone and iOS over the past few years. While older devices can still be easily scraped of personal data with forensic tools, newer devices are notably harder to crack. However, the new fixes won’t help every iPhone or iPad user going forward. Users who don’t use two factor authentication (which there’s a three-day waiting period to sign up for) or upgrade to iOS 8 will continue to be easy targets, especially if they don’t react quickly to account alerts.Cracking a brand new iPhone through the front door is hard. However, there are still a statistically significant number of older devices in circulation,even based on a look at the agent information from Ars' visitor logs. And many users leave their phone less secure by sticking with the default 4-digit PIN,

iCloud busting, phase 1: With professional tools

It's important to note that Elcomsoft built its tools without any help from Apple—they're based entirely on reverse engineering of Apple's protocols. Elcomsoft is just one of a number of forensic tool vendors that gives investigators the ability to exploit seized smart phones and laptops to extract personal data. Cellebrite, Oxygen Forensics, and AccessData are just a few of the commercial tools vendors that also offer ways to crack iOS devices of varying vintage. Oxygen Forensics offers a free 6-month trial download of its suite to anyone willing to give up their email address. There are also open-source tools, such as the iPhone Backup Analyzer.

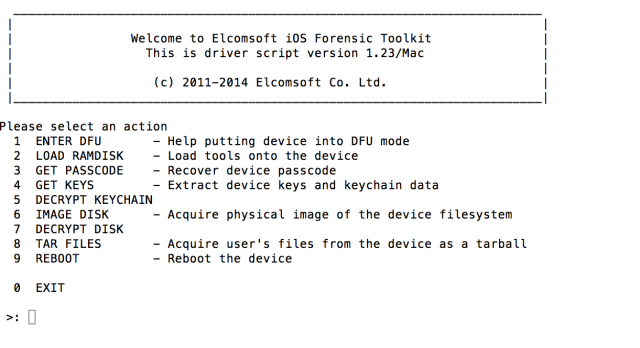

In our first assault on iPhone data, we employed that Elcomsoft pair—iOS Forensic Toolkit (EIFT) and Elcomsoft Phone Password Breaker (EPPB). Elcomsoft iOS Forensic toolkit, which we ran on an Apple MacBook Pro, is a command-line tool that uses a jailbreak to give the user the ability to bypass the security of an iOS device. It also allows you to decrypt and download an image of its contents. The tool is available for Windows as well, and it requires a USB “dongle” to operate. (That's an anti-piracy measure that allows the company to control its distribution.)

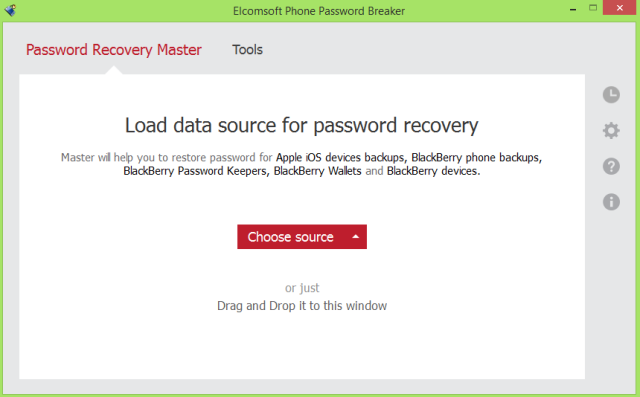

EPPB, on the other hand, is a Windows-only tool that uses a standard installation key. It gives users the ability to recover passwords from iPhone phone backups on a PC or to grab the contents of an iPhone backup from an iCloud account. It can also crack BlackBerry passwords, but that’s an experiment for another story.

EPPB requires you to have at least one of the following things:

- The target’s iCloud password—by them volunteering it, through a phishing attack, or by gaining access through other social engineering.

- Access to a computer with iTunes and a local backup of their iPhone.

- Access to a computer with their stored iCloud credentials in a token—either with the phone owner’s credentials or as root. The token, which is stored locally by the iCloud control panel on Windows and by Mac OS X’s built-in iCloud keychain, can be extracted by another Elcomsoft tool, allowing EPPB to act like it’s a device already trusted by iCloud.

First, we tried using EIFT to go after our iPhone 5S. That turned out to be a mistake, as the toolkit depends on a “jailbreak” that doesn’t work on more recent iPhones. Elcomsoft CEO Vladimir Katalov said in an e-mail, “iPhone 5S (as well as iPad Air and iPad Mini with Retina, i.e. all 64-bit devices) are not supported by EIFT yet. We are working on that, but analyzing 64-bit ARM code is a nightmare.” The attempt ended up putting our phone in recovery mode, resulting in an ironic restoration from an iCloud backup.

However, the EIFT attack was super-effective on an old iPhone 4 on the first attempt—largely because the target (my wife) hadn’t updated iOS since version 5.1. We were quickly able to bust the passcode and image the device’s contents as a set of .DMG files on my Mac.

Next, we upgraded the device to the current iOS 7 release and tried again. This time, EIFT stumbled on recovering the passcode for the device, but it was still able to get an image of the contents of the phone's “user space.” This should serve as a reminder: when trading in or recycling old iPhones, make sure to do the “factory wipe” on data beforehand. Otherwise, someone could be harvesting your data off that old phone.

Next, we shifted tactics away from the iPhones themselves and went after what is currently perceived as the softest target—iCloud backups. Using EPPB, we downloaded the full backup contents of our iCloud account, discovering there were three date-stamped backup images waiting to be plundered for data. Protected only by the iCloud password, EPPB was able to extract these in less time than it takes to restore an iPhone 5S.

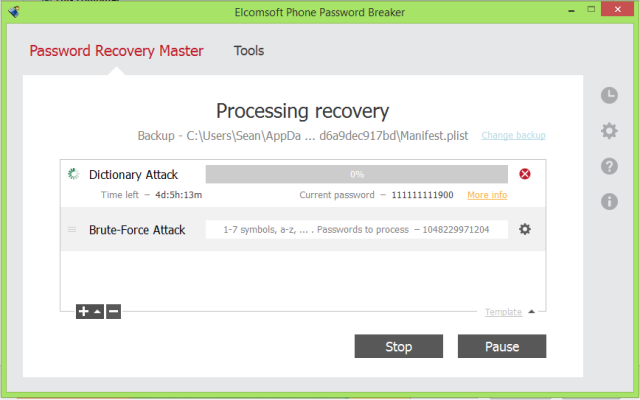

We also went after a password-encrypted version of the backup on a local drive using EPPB’s dictionary and brute-force password attacks, cracking the seven-letter password after about two days of hammering the file on an ancient HP dual-Athlon machine. Until recently, the same sort of attacks could be launched (albeit in extreme slow motion) against iCloud without triggering an alert.

Password-guessing and brute-force attacks aren’t the only ways an attacker could get a target’s iCloud credentials. There’s been a recent wave (at least in our e-mail) of Apple iCloud account phishing attacks. While most of these have been pretty obvious (Apple would never allow e-mails with that many typos to go out), a well-thought-out phishing attack could be used to throw a user into a panic—for example, by suggesting that their iCloud account has been compromised.

And since the iCloud backup is only protected by the iCloud password right now, once someone has obtained that password, everything in that backup is wide open. And there’s a lot in that backup.

reader comments

133