I live one block away from a McDonald’s that, up until this year, I never patronized. My neighborhood technically counts as a part of Seattle, but it’s just far enough away from the denser, hipper parts of town that it has room for big parking lots and giant chain stores—prime real estate for your Home Depots, your malls, your Mickey D’s. I’m not as chain-averse as many in the Northwest, but I still rarely heed the call of the golden arches.

Things started to change when I upgraded my personal smartphone to an LG Nexus 5 and started fiddling with the options menus. Since I never owned an NFC-equipped smartphone before, I took a deep dive into Google Wallet, wondering if the app would work at any nearby tap-and-pay kiosks. Ultimately, I loaded my credit card information into the app months ago then forgot about it.Fast forward to a random, sunny day in which I went on a much-needed jog, the kind that lasted long enough to work up an appetite. I was close to finishing, and all I had on me were my phone and a pair of headphones—yet I knew I’d be returning to a house sorely lacking in food. Suddenly, there was that McDonald's. I had a hunch that a giant restaurant chain might be the perfect place to find an NFC-compatible payment kiosk, so I made the one-block-away pit stop. A crowd of teens watched as I tapped my phone on the McDonald’s register and paid $1.63 for a chicken sandwich.

“Yo, is that the new iPhone?” an older teen asked. I said it wasn’t but that a lot of new phones can pay this way. He pulled his iPhone out and looked at it, seemingly disappointed. “I gotta get up on that.”

It's only one anecdote, but this simple chicken sandwich to-go perfectly demonstrates how shopping has started to change forever. Every year, smartphones in America edge closer to becoming as ubiquitous as wallets, and it's a fact that merchants have been trying to maximize for some time.

Declaring that “phones change shopping” can’t be followed with a simple, one-dimensional explanation. The excitement and confusion over mobile commerce comes precisely from its fractured state—the myriad ways we can shop and consume through our handy, dandy phones, and the various apps and designers who are each trying (and often failing) to make the most of that. But even now, how we buy directly influences what we buy. And savvy sellers who enter this ecosystem correctly will have dibs on our last-minute, end-of-jog sandwich purchases—as well as just about everything else that we can instantly spend money on.

What's in it for us?

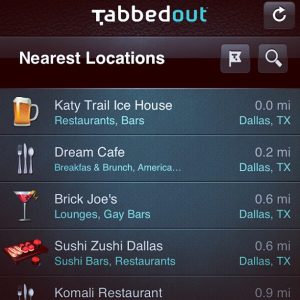

In 2010, restaurants and bars across the United States started filling their tables and bartops with little placards advertising an app-driven service called TabbedOut. The idea seemed brilliant at the time. Why should diners and drinkers have to wait to ring up their tabs, especially during a busy happy hour or last call? Instead, people could load the TabbedOut app when they were ready to leave, confirm the purchase via credit card, and be on their way.

Up until very recently, most mobile transaction start-ups and attempts struggled because of these sorts of awkward hand-offs. Buyer and seller each had to scan a QR code or load an alphanumeric code, and this process often required merchants to buy a new piece of hardware or pay for a software license to add to their current point-of-sale system. Every slice of the smartphone-shopping pie required adding cost or complication, all to cater to a shopping niche that wasn’t growing organically.

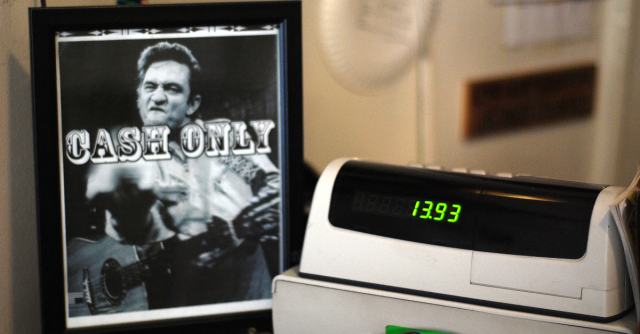

Further complicating such adoption has been a blatant imbalance between how merchants benefit compared to how shoppers benefit through apps and mobile platforms. Recent privacy concerns about the CurrentC app magnify the looming issue at hand. Users cough up a ton of data directly to a retailer when using a shopping app as opposed to when they simply pay with cash.

“Retailers who are building apps seem thus far to have been more focused on data mining and ad sales and convincing users to be social within their app or receive push notifications than they have specifically trying to build payment infrastructure and use the app to buy stuff,” Marketplace Tech host Ben Johnson said. “For example, Ticketmaster’s app lets you buy tickets, but they won’t cop to the anecdotal information that suggests it’s easier to buy a ticket through a Web browser than through their app.”

Osberg points to other merchant benefits, like real-time sales data analytics when these apps are used, but what do we as shoppers get out of that? No major merchant group has compensated with an app that supports, say, doling out frequent-shopper points or other benefits in exchange for passively sharing their data.

“We in the tech world are willing to fiddle with new methods, but we’ve still yet to find a real reason why an average shopper is going to try to pay with a phone as opposed to a card out of the wallet or purse,” Osberg said. He pointed to a statement from former Visa executive Jennifer Schultz who ran the credit card’s unpopular “V.me” digital wallet initiative. “People just don’t have problems swiping a card,” Osberg recalled her saying. “It’s easy to do.”

“Ultimately, every [merchant] is trying to reduce friction when a user wants to spend money,” Johnson said. “They want to use their device to do it and use their device in environments where it’s recognized what they’re trying to do without them trying to say what they’re trying to do.” In most shopping situations, cash or credit accomplishes that goal without requiring a password, an app load, or another hurdle. Essentially, here’s what I want, and here’s a one-step way of giving you money. Done.

In that light, the real beginning for mobile adoption has come from all-in-one services where a phone’s functionality turns a multi-step process into something simpler. Johnson pointed to ride-sharing services like Uber and Lyft as the ultimate proof of mobile pay’s power.

“I can use my phone and its location to access a service and pay for that service without ever having to take my phone out again,” Johnson said. “Once I call the car, the only thing I’m pushed to do by the app is rate the driver. It just charges my wallet. I can just step out of the car.”

Car-sharing apps have helped us say goodbye to the standard taxi pain of negotiating an end-of-ride payment, and we figure that was at least some of the reason why Uber was able to announce a jaw-dropping $17 billion valuation this summer. While cities have argued over—and attempted to legislate—some ride-sharing issues, the cork’s been popped in terms of how people want to hail and pay for cabs. There’s no going back.

reader comments

87