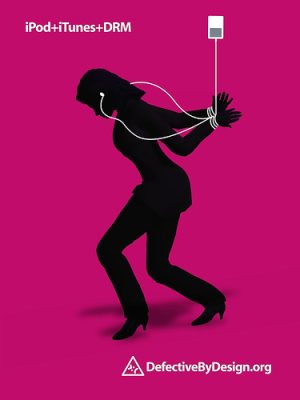

Lawyers representing a class of nearly eight million consumers will put their case to a jury of eight men and women in an Oakland federal courtroom. The plaintiffs say that Apple's "FairPlay" system "locked in" its customers, making it costly to switch to technology built by competitors like Real Networks.

Apple says its pricing didn't even take into account Real Networks, which had a mere three percent of the online music market back in 2006.

Plaintiffs say the "lock-in" caused consumers to be overcharged tens of millions of dollars. Pre-trial documents indicated that plaintiffs' lawyers, representing a class of about eight million consumers who bought iPods from 2006 to 2009, will seek as much as $350 million in compensation.

Jury selection took place before the Thanksgiving holiday, leading to the panel that will gather this morning. The trial could take as long as three weeks.

The most anticipated part of the case is the fact that onlookers may get a chance to hear from Steve Jobs. Plaintiffs' lawyers have access to e-mails from Jobs that are relevant to the case, and they deposed him before his death in 2011.

“We will present evidence that Apple took action to block its competitors and in the process harmed competition and harmed consumers,” plaintiffs' lawyer Bonny Sweeney told The New York Times.

Apple's legal team is betting a few hundred million dollars it can combat that portrayal at trial.

It's the second case this year in which Apple has vigorously contested the suggestion that it competed unfairly. In a case involving the pricing of e-books, the company lost to the government at trial but continues to fight through appeal. It also settled an antitrust class-action, structuring a lower payment to the plaintiffs if they beat the government's case.

Jury selection

The jury was picked in about five hours at a pre-trial hearing a few days before the Thanksgiving holiday. Of the eight-person jury, one is a programmer and two are engineers whose answers to questions suggested at least some coding experience.

Two of the prospective jurors—neither of whom was ultimately seated—said they had met Jobs in person. One man said Apple was a major client of his, constituting around half his income. He kept the description of his work vague but said he answered Jobs' questions about a "setting in a theatrical application" once. He was dismissed for cause.Another man said he ran his own IT company for about 10 years and in the course of that business met Jobs "two or three times." Plaintiffs' lawyers used one of their three strikes to remove him from the jury.

Plaintiffs' lawyers also struck a real estate attorney after voicing concern the large law firm he worked for did a large amount of antitrust defense work. They struck a female musician who said she "loved" all her Apple products.

Apple lawyers struck one juror who had described Jobs as an "a—hole" on his juror form. That juror said "corporations get a lot of tax breaks that I don't agree with... they're motivated by profits and their shareholders, versus the interest and well-being of the people that work there."

Apple's team also struck a man who said he was only "somewhat" satisfied with Apple, described DRM as "sort of a hindrance," and relayed a story about how his brother's iPhone 4S was "bricked" after he upgraded the operating system.

Apple didn't strike an engineer who worked at Google, even though he complained directly about DRM generally, saying it had "destroyed sharing," and Apple DRM in particular.

"I remember it coming out, and it severely limited the sharing you could do with the music that you had," said the engineer. "Even music you owned off CDs, you wondered if you could make copies and use it on multiple machines... It was very frustrating at the beginning."

After the jury was selected, the judge reminded the jurors not to talk or read about the case.

"I thank you again for your service and for honoring the Constitution," she said. "Have a terrific day, you are all dismissed."

Listing image by Free Software Foundation

reader comments

245