Ten years ago, a weekend journey to a friend’s wedding was likely to involve typing a postcode into Multimap, printing out step-by-step instructions and then enduring amateur navigation from your partner in the passenger seat.

A decade on, digital maps and the inexorable rise of the smartphone have radically changed how we locate, navigate and plan our journeys. Mobiles, satnavs and computers act as our guides for everything from driving holidays to nipping to the shops.

Apps such as Google Maps have become the de facto interface between the the physical and the digital world, meaning people need never be lost again - even if they don’t have a sense of direction.

While Sir Tim Berners-Lee’s nascent world wide web supported the first online maps in 1993, it wasn’t until the launch of Google Maps ten years ago today that digital maps began to enter the mainstream.

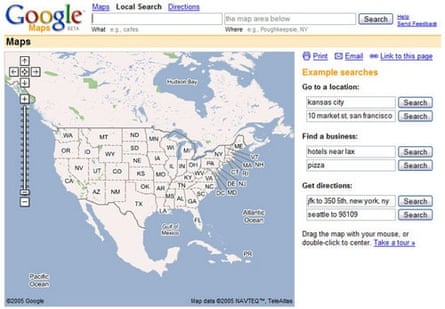

In 2004, Danish brothers Lars and Jens Eilstrup Rasmussen went to Google with an idea for a web app that would not only display static maps, but provide people with a searchable, scrollable, zoomable map.

Google acquired their company Where 2 Technologies - along with a second company called Keyhole developing the geospatial visualisation software that would become Google Earth - and the new team of 50 people set out building Google Maps.

Google Maps launched in the US on 8 February 2005 and in the UK two months later, though by that time it wasn’t the first digital map of its kind: Yahoo had beaten Google to it with a redevelopment of its long-standing Yahoo Maps in 2004.

“Yahoo beat Google to web maps and MapQuest beat it to turn-by-turn directions, but people didn’t stand up and take notice until Google Maps came along,” said Gary Gale, the Ordnance Survey’s head of APIs. “It wasn’t the first out there, but the role of Google Maps in transforming digital maps, making them popular and bringing them from a tech niche into the public consciousness cannot be underplayed.”

Google Maps didn’t stand still. Later in 2005 Google launched driving and public transport directions, but it wasn’t until the launch of satellite imagery that Hanke saw how committed Google was to the project.

“Our aim was to create one seamless, browsable map of the entire world – an Earth that you could browse,” John Hanke, co-founder of Keyhole and vice president of Google’s geospatial division until 2011 told the Guardian. Google’s co-founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page, he said, thought that geospatial – data and information related to maps and location services - was a key element of Google’s organising the world’s information.

“At the time satellite imagery was quite expensive to acquire and scarce because there weren’t that many satellites available. I went to show Sergey on the map all the major cities we wanted to acquire. He looked and he just said, ‘why don’t we do all of it?’”

Street View was Larry and Sergey’s idea

Street View has proved to be one of Google Map’s most controversial but popular features. Launched for select US cities in 2006, and rolled out to Europe, Japan and Australia in 2008, the service relied on building up pictures of every street in the city using a specially equipped camera mounted on a car.

“Larry and Sergey had toured around the Stanford campus with Larry taking photos out the window of a car with a dSLR camera to experiment with stitching them together,” said Hanke. “That was their idea, but it took a partnership with Stanford and Sebastian Blune to make it work.”

Each car was fitted with a range of sensors including GPS, which allowed Google to trace routes and meant the company no longer had to reply on data from third parties.

The cameras also captured road signs, house numbers and other data not visible from the sky, giving its maps local knowledge of no-turns, speed limits and other street rules. This was all part of what Google termed “Ground Truth”, aiming to create the most accurate, detailed maps possible.

Google Maps debuts on Apple’s first iPhone

Google Maps first appeared on a smartphone in 2007 on Apple’s first iPhone - a very different era when Google and Apple were partners more than rivals as they are today.

“Smartphones were the key crystallising moment causing people to fall back in love with the map,” said Gale. “Digital maps are essential to everyday life – you wouldn’t buy a smartphone without them.”

“Steve Jobs called me at my desk to ask me to help out on a project – he wouldn’t tell me what it was, but of course I knew,” said Hanke. “We worked closely with Apple to get maps ready for the launch of the first iPhone, which opened up so many possibilities.”

Google Maps has since added turn-by-turn satellite navigation, Zagat restaurant ratings, traffic updates and expanded Street View to include Venetian canals and the Grand Canyon - yet progress has not always been smooth.

In 2010 it was revealed that Street View cars had also been capturing information about private Wi-Fi networks as they roamed the streets of US and Europe, prompting a $7m fine from US authorities. The service’s expansion into Europe, especially in Germany, also caused home owners to take issue with their property being captured and placed online for the world to see without their permission.

“We were doing something that hadn’t been done before,” said Hanke. “People had put up with surveyors going out with range finders and survey equipment, but now cars with cameras were doing the work. It was a learning process for us, the whole idea of photography in a public space and what it means; it was a big cultural shock and we were part of it.”

And the competition?

Google Maps faces ever increasing competition. Some, such as popular third party travel app Citymapper, use Google’s own mapping data, while other services have created their own geospatial resources.

Apple turned from partner to competitor in 2012, deciding to dump Google Maps from the iPhone for Apple Maps. The company quickly learned that making a solid map service was more difficult than it looked, forcing chief executive Tim Cook to publicly apologise for the bug-ridden product. Today it is a viable alternative and gaining in popularity as the default maps app for the iPhone, iPad and Mac computers.

Microsoft’s Bing Maps was one of the first to improve upon top-down aerial images, introducing a birds-eye view that allows browsers to see streets and buildings from a 45-degree angle.

Nokia also acquired the largest maker of automotive-grade map data, Navteq, in 2007 and has been using it to build highly accurate maps which it sells to other companies, including Garmin, BMW and Amazon.

Beyond the professional maps, there are also collaborative projects such Open Street Map creating free, editable maps of the world and relying on users to correct things that are wrong in much the same way as Wikipedia.

“The mapping war isn’t over, and it won’t ever be,” said Gale. “It’s all about the fight to keep the map accurate and to give it context. A map is never finished, there is always more to be done. Anyone who gives people and business what they want, making it valuable to them will win.”

The future of maps is indoors, and offline

For Gale, the next five years in mapping technology will be about a new generation of sensors to take over from GPS and mobile phone signal triangulation.

“The moment we get cut off from GPS the mapping experience becomes rubbish. We need something to fill the gap for mapping indoors, where accurate positioning is difficult. We’re not clear on what that will be yet – whether Bluetooth beacons or another suite of sensors,” Gale said.

The future of the digital map, however, is not actually of the map, but using the map. Projects like those created by Hanke’s own Niantic Labs are good examples.

Field Trip, for instance, uses location awareness to notify users of interesting landmarks, features and places in the real world. Another, Ingress, is a location aware game that overlays a virtual playing field on top of our towns and cities.

These are the next evolution of the map, humanising and contextualising location to make it more relevant to us.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion