In the last two-to-three years, that gap has narrowed substantially. The Air has become more powerful and less compromised, while the Pro has slimmed down and dumped features like user-replaceable RAM and its Ethernet jack. Both use Thunderbolt 2. Both use modern dual-core CPUs with some of Intel’s better integrated GPUs. They’re even priced in the same ballpark. What was once an easy recommendation has gotten more difficult.

Last year as part of our review process, we took a good long look at both laptops, picked the best and worst things about each, and made purchasing recommendations based on what you need in your 13-inch Mac laptop. We’ll post similar individual reviews soon to better consider how each computer stacks up compared to the wider PC market, but this piece serves a very specific purpose.

If you're interested in a new Mac laptop but shy away from the extremes (the extreme power of a 15-inch Pro, the extreme portability of an 11-inch Air), which new 13-inch offering do you buy?

| Specs at a glance: | 13-inch 2015 Apple MacBook Air | 13-inch 2015 Apple Retina MacBook Pro |

|---|---|---|

| Screen | 1440×900 at 13.3" (128 PPI) | 2560×1600 at 13.3" (227 PPI) |

| OS | OS X 10.10.2 Yosemite | OS X 10.10.2 Yosemite |

| CPU | 1.6GHz Intel Core i5-5250U (Turbo up to 2.7GHz) | 2.7GHz Intel Core i5-5257U (Turbo up to 3.3GHz) |

| RAM | 4GB 1600MHz LPDDR3 (soldered, upgradeable to 8GB at purchase) | 8GB 1866MHz LPDDR3 (soldered, upgradeable to 16GB at purchase) |

| GPU | Intel HD Graphics 6000 (integrated) | Intel Iris 6100 (integrated) |

| HDD | 128GB PCIe 2.0 x4 solid-state drive (upgradeable to 256GB or 512GB) | 128GB PCIe 2.0 x4 solid-state drive (upgradeable to 256GB, 512GB, or 1TB) |

| Networking | 867Mbps 802.11a/b/g/n/ac, Bluetooth 4.0 | 1.3Gbps 802.11a/b/g/n/ac, Bluetooth 4.0 |

| Ports | 2x USB 3.0, Thunderbolt 2, card reader, headphones | 2x USB 3.0, 2x Thunderbolt 2, HDMI, card reader, headphones |

| Size | 12.8" × 8.94" × 0.11-0.68" (325 mm × 227 mm × 3-17 mm) | 12.35" × 8.62" × 0.71" (314 mm × 219 mm × 18 mm) |

| Weight | 2.96 lbs (1.35 kg) | 3.48 lbs (1.58 kg) |

| Battery | 54Whr | 74.9Whr |

| Warranty | 1 year | 1 year |

| Starting price | $999.99 | $1,299.99 |

| Price as reviewed | $999.99 | $1,299.99 |

| Other perks | Webcam, backlit keyboard, dual integrated mics | Webcam, backlit keyboard, dual integrated mics |

External changes

Winner: N/A

For both laptops, external changes are few and far between. In fact, the MacBook Air design is fundamentally the same one Apple has been using since 2010. There are no external changes. It’s not a bad design—the keyboard and trackpad are good and build quality is great. Windows 10 and PCs with Microsoft’s Precision Touchpad spec are only just beginning to approximate the functionality of Macs' accurate, responsive trackpads. But we're five years out from this design's debut, and it could use some streamlining.

On the other end, the design of the smaller Retina MacBook Pro is younger than the Air’s. Though this is the same design Apple has been using since 2012, it feels less in need of an overhaul. The aluminum unibody design actually isn’t all that far off from the 13-inch Air’s, though it has a smaller footprint and is the same thickness throughout, where the Air is tapered. It has the same keyboard and a faster version of the same basic technology at its heart (more on that in a bit).

The only external change to the Pro is the addition of Apple’s Force Touch Trackpad, originally developed for the Retina MacBook. To accommodate that system’s thinness, the trackpad doesn’t physically move as most current trackpads do. This isn’t something that Apple did first—Synaptics has shipped a clickless ForcePad for years—but Apple’s implementation is the first that approximates the feel of a standard trackpad. It’s also pressure sensitive and can respond differently depending on how hard you press down.

iFixit’s teardown of the MacBook Pro explains how the technology works—strain gauges provide the pressure sensitivity, and electromagnets vibrating against a metal rail provide the haptic feedback that approximates a “click.” Going to the Trackpad preference pane lets you configure the amount of haptic feedback and whether the “force click” feature is enabled or not.

At the “firm” feedback setting, the Force Touch trackpad comes the closest to recreating the feeling of the regular trackpad that’s still in the MacBook Airs. It’s not quite the same, but it’s close enough.

Clicking and holding your finger down for an extra second will invoke a force click, which will show you some context-sensitive information based on what you’ve clicked on—we’ve highlighted some of the possibilities for Apple’s own apps in the gallery below. Applying different amounts of pressure to the trackpad also does things in certain apps. Scrubbing through a video at different speeds is one example Apple used, and if you’re drawing lines or a signature in Preview, different pressure levels make your lines thicker or thinner.

-

The Force Touch Trackpad is visually similar to the Mac trackpads that have come before.Andrew Cunningham

-

System Preferences picks up a few new options you can use to configure the trackpad. We like the "firm" setting the best.Andrew Cunningham

-

Force click by holding down on the trackpad until you feel a second vibration. Depending on what you click, OS X will pull up relevant information about it from Wikipedia or elsewhere.Andrew Cunningham

-

The dictionary definition. In the Finder, force clicking can be used to activate Quick Look or rename files.Andrew Cunningham

-

Force click on an address or location to pull up maps.Andrew Cunningham

-

Creating calendar appointments is also possible, though we'd like it if force clicking would pick up details about the event other than the date and time.Andrew Cunningham

Occasionally we would press and hold the trackpad so we could drag an item somewhere only to have the trackpad register it as a force click, but for the most part these features work fine. If you use lots of third-party apps, you'll need to wait to take advantage of force clicks, though—all of Apple's built-in apps appear to support it at this point, but you can't force click text in apps like Chrome or Microsoft Word. We'd imagine that basic support is relatively easy to add, but you'll be waiting for a while before apps begin to take advantage of it (think back to the amount of time it took for the ecosystem to introduce support for things like Full Screen mode).

Neither force clicks nor pressure sensitivity are transformative in the way that the original one-piece multi-touch trackpads were. Once you got used to using those trackpads to switch between Spaces desktops and Full Screen apps or invoke Exposé/Mission Control, it sucked to go back to the previous simple-trackpads-with-buttons that Apple had been using before—they change the way you multitask on your laptop. As for the Force Touch trackpad’s new features, you’ll be glad that they’re there, but you won’t really miss them if they aren’t.

The Force Touch Trackpad’s inclusion in the MacBook Pro, a computer with plenty of space for a trackpad that actually clicks, is a signal that we can expect the Force Touch trackpad to be the new “normal” going forward. The existence of OS X features tailored specifically to this trackpad is another signal. Expect most Macs introduced this year and next to make the jump.

Display

Winner: Retina MacBook Pro

This is an easy one.

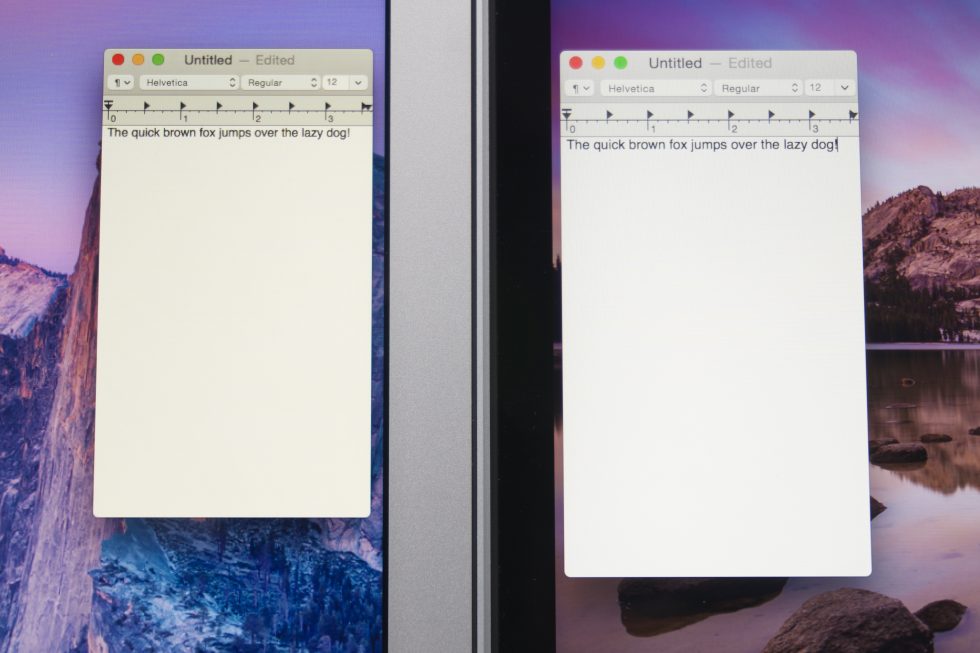

The MacBook Air’s biggest deficit at this point is its screen, which was pretty good compared to contemporary laptops four or five years ago but is nothing special now. Viewing angles are OK, but there’s a fair bit of color and brightness shifting if you look at the screen from the top or sides. But most PC makers will sell you a 1080p-or-better IPS screen at this price. They’ve gradually become the worst screens Apple ships on any of its products.

The retina screen on the MacBook Pro is an upgrade in every way. It’s much sharper (227 PPI compared to about 128 in the Air), and it’s got superior color and viewing angles. Our only real complaint is that its “effective” resolution of 1280×800 is low, especially for the pros to whom it caters. Setting it to 1440×900 or 1680×1050 mode is an easy fix, and the GPU handles it with no problem. It just comes with a slight fuzziness relative to native resolution.

reader comments

237