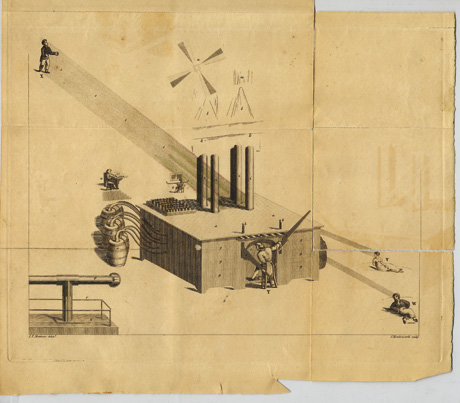

Describing the path of technological progress, Marcelo Rinesi likes to point out an early 19th century drawing by a paranoid schizophrenic Welsh man named James Tilly Matthews. The sketch, reproduced in a book called Illustrations of Madness, is considered to be one of the first published pictures by a mental patient.

It depicts a so-called Influence Machine, a term psychiatrists borrowed from the study of static electricity to describe the elaborate mechanical contraptions drawn by schizophrenics to explain their delusions. The devices and the eerie common way that patients described them appeared to derive from the Industrial Revolution and humans’ unsteady relationship with the inanimate. Matthews dubbed his own Influence Machine the "air loom." The gas-powered instrument was a device that, according to Matthews, communicated with a magnet planted inside his brain. It would allow French agents to see into his thoughts and control him from afar using radio waves and other then-mystical technology.

"It’s tragic, but it’s also very funny because it’s basically Google and Wi-Fi," Rinesi says. "For him, it was a paranoid delusion. But he was describing what, for us, is daily life." Technology companies don’t need to pry into our brains to exploit us, Rinesi says; they have built windows into them, and those windows are open all the time.

Rinesi, a data intelligence analyst who lives in Buenos Aires, Argentina, splits his time between freelance work and his role as chief technology officer for the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies (IEET). The non-profit organization, founded in 2004 by philosopher Nick Bostrom and bioethicist James J. Hughes, believes that technology can positively impact society only if it is evenly distributed and does not manipulate or exploit its users. Lately, the IEET and Rinesi have focused on the ongoing Volkswagen emissions scandal. That auto software would help lie to regulators, and hide itself from car owners, is a revelation so enormous — its betrayal of customers so profound — that it threatens to bring down the largest automaker in the world. It’s also a sign of the times we live in.

Rinesi says the technology industry of today has created an apparatus through which corporations can exploit consumers, thwart regulation, and maximize profit with minimal repercussions. That apparatus is founded on the consumer's decision to willfully ignore the risks of mostly free technologies, and the government’s failure to regulate them on our behalf. Rinesi says paranoia about the world’s most powerful companies and their products is intrinsic to our ever-evolving relationship with technology. But now the suspicions are moving from the paranoid to the reasonable.

Suspicions are moving from the paranoid to the reasonable

If the last two decades have been about gifting the world technological progress in the form of computers, smartphones, and connectivity, the coming years will be about using the computer’s ubiquity to connect everything else in the world. The "Internet of Things" (IoT) is a phrase referencing a future where every object, from cars and buildings to toasters and thermostats, communicate to help us live better lives.

We’ll save money, the theory goes, because efficiency and optimization will be automated. We’ll save resources because our infrastructure will be algorithmically driven. We may even find ourselves healthier, as more data is collected and funneled into the health care system to inform technologies designed to detect or prevent illnesses. But the downside is that we’re opening up our entire physical infrastructure to the ambiguities of modern technology, which loans us products and possibilities at the expense of consumer protection.

"The Internet of Things could be a great platform to help us be smarter, safer, and so on. It’s not going to be like that," Rinesi says. "In practice, it’s going to be a platform for advertising and user tracking and charging you as much as they can for a coffee." Just as Google hands us an email account and the entire planet’s knowledge in searchable format, and Facebook offers us the ability to connect with billions of people, the real world may find itself filled with the same trade-offs we’ve opted into online as a matter of participating in modern society.

Keurig gave it a shot, ignorant to the potential aftermath

Think Keurig, which tried to ape the printer-and-ink business models of companies like HP to prevent customers of its 2.0 brewer from using third-party coffee cups to brew their drinks. The company used special scanning software that would only allow the brewer to use Keurig products. Consumer backlash, falling sales, and lawsuits forced a retreat. But Keurig gave it a shot, ignorant to the potential aftermath.

That type of behavior sets the standard for what we may expect in the future, as more companies begin tapping into the control offered by modern software to promote their own products, collect more data, and find ways around regulations. Rinesi used the Volkswagen scandal as a jumping-off point to rearticulate his concerns in a post for the IEET about how the IoT could give rise to machines with ulterior motives.

Is your self-driving car deliberately slowing down to give priority to the higher-priced models? Is your green A/C really less efficient with a thermostat from a different company, or is it just not trying as hard? And your TV is supposed to only use its camera to follow your gestural commands, but it’s a bit suspicious how it always offers Disney downloads when your children are sitting in front of it.

In other words, as the march of technological progress fuses software with the physical world, the types of regulatory oversight and protection afforded to physical industries will falter in the face of software that can be manipulated. Rinesi says the challenge for our legal framework is that it’s based on a mechanical world, "not one in which objects get their software updated with new lies every time regulatory bodies come up with a new test."

The opportunity to design physical objects that operate as much against us as they do by our command will not be limited to singular bad actors. Technology today has become a complex web of competing interests, forced compromises, and wary partnerships. Apple and Samsung compete fiercely on a smartphone’s end product, but the former buys components from the latter out of necessity. Could a Samsung-made iPhone chip result in purposefully poorer battery life than one made by Apple’s other partner TSMC? It’s a conceivable situation, for both smartphones and cars if, say, Mercedes begins supplying Ford with adaptive cruise control software that’s less fuel-efficient in a Focus than it is in an S-Class.

"Our physical infrastructure, cars are part of it, are built assumed that they are stable, work well, and we understand them," Rinesi says. As soon you marry an object to the world of computers, however, you insert ambiguity, he adds. "Nobody knows the full stack any more."

"It’s so bad. In fact, it’s certain companies don’t know all the ways their product works," says Colby Moore, an R&D security specialist at Synack, which deploys teams of hackers to purposefully break through cybersecurity systems to better improve them. "Until it breaks, they don’t need to go look for it." Moore says it’s inconceivable for a smartphone or car manufacturer today to know everything about how their respective machines function. Even within large organizations, individuals now have the leeway to betray the will of higher-ups.

Volkswagen’s US CEO Michael Horn said he was unaware of the mechanism inside the company’s vehicles that let it cheat on emissions tests. Instead, he blamed the implementation on "a couple of software engineers." Whether that remains true for Volkswagen, it’s a tacit admission that rogue employees anywhere could alter critical software to thwart regulations in the name of profit.

It would be easier if these fears about technology were traceable to paranoia, says Ian Bogost, as it would imply a complex conspiracy. "I’d almost be better," he says. In reality, "it’s worst than that because it’s so haphazard and random." Bogost, a game designer and professor at Georgia Institute of Technology who writes about technology for The Atlantic, says there is reason to be deeply concerned that the tech sector is able to do what it pleases as it becomes more intertwined with the physical world.

Regulating the world of connected everythings

"A tipping point here is more about what are the appropriate ways to regulate the world of computational everythings," he says. In an Atlantic piece titled "The Internet of Things You Don’t Really Need," Bogost argued that the IoT has been subsumed for now by the litany of Kickstarter-hungry startups that offer little value by connecting our cups and gas grills via Bluetooth. The end goal, however, is a longer-term ploy to ensure that whatever language physical objects speak in the future and the data they collect traces back to the same power brokers in the industry, the Googles and Microsofts and Amazons of the world.

"If the last decade was one of making software require connectivity, the next will be one of making everything else require it," Bogost wrote. "Why? For Silicon Valley, the answer is clear: to turn every industry into the computer industry. To make things talk to the computers in giant, secured, air-conditioned warehouses owned by (or hoping to be owned by) a handful of big technology companies."

This realm will be no more regulated than the world of computers and software, which Bogost points out has enjoyed a lack of oversight as tech companies have replaced energy and financial institutions as some of the most powerful entities on the planet. The worry is not about whether we should put computers inside everything; that will inevitably happen. It is rather about what companies will do with them and whether any regulatory body will be able to keep up.

"It’s not really computers that are the problem. It’s the particular kind of corporate action," Bogost says of the willingness to act first and ask forgiveness later. It’s the (now publicly retired) "move fast and break things" philosophy of companies like Facebook that would sooner emotionally manipulate hundreds of thousands of users via its News Feed, as it did last year in a controversial research study, than openly ask them permission to do so beforehand.

"Can you imagine a civil engineering firm with a motto like ‘move fast and break things'?" Bogost asks. It’s not unreasonable to consider many of today’s tech titans as infrastructure companies as much as they are software makers. Google is developing self-driving vehicles, and Facebook is building internet-delivering airplanes. Meanwhile, Uber is bending worldwide labor laws and transportation regulation to its will, and Amazon is helping pave the way for a sky filled with drones. Facebook’s new motto, unveiled last year, is "move fast with stable infrastructure."

With the IoT, the stance is similar. "One thing that we absolutely believe is that though that we hear the conversation around policy, we don’t want policy to get in the way of technological innovation to solve some of these challenging problems," says Rose Schooner, Intel's chief strategist for the IoT.

"We don't want policy to get in the way of innovation."

Bogost says there may be a movement afoot among governments to reclaim regulatory power. It’s seen in Europe’s push back against Google in both antitrust and privacy matters and bolstered by efforts in the US to reel in potential labor abuses in the sharing economy. The Volkswagen incident, too, will have ripple effects, if only because of the reported financial devastation it will cause the car maker and the influence it will have on future emissions testing and corporate misconduct.

"Rather than this amorphous, anonymous worry, it’s an invitation to reflect on the fact that we do have infrastructures for that type of control, we used to employ them," he says. Instead, we’ve allowed the erosion of regulatory intervention in the tech sector, in part because it’s easier to accept a rosy picture of the future than it is to warn about the risks. "The tech sector is very much in support of that erosion," Bogost adds.

There is not much that can stop technology’s absorption of the physical world. Your next car, whether it’s a Volkswagen or a Honda or a Tesla, will look and feel like a motor vehicle. But it will contain more computers. In fact, it will have dozens of them, controlling nearly everything about the vehicle and, in due time, driving it for you as well. And those computers will operate thanks to software — relying on protocols you’ve never heard of, taking commands from algorithms you will never understand, and communicating in a language you don’t speak. Some of that software may not be in the best interest of you or society, and you will likely not know it’s there. That is, until someone finds it.

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/15542179/Internet_of_Things_Shutterstock_final.0.0.1445452123.jpg)