There's been a lot of bluster about the ongoing encryption saga between the FBI and Apple. "So Apple recently joined ISIS," The Daily Show's Trevor Noah joked this week. CIA Director John Brennan's view was a tad more serious. "What would people say if a bank had a safe deposit box that individuals could use, access, and store things, but the government was not able to have any access to those environments?" he told NPR's Morning Edition. "Criminals, terrorists, whatever could use it. What is it about electronic communications that makes it unique in terms of it not being allowed to be accessed by the government when the law, the courts say the government should have access?"

Let's start with the facts. Apple is currently fighting a court order obtained by the FBI. The FBI wants Apple to build software to help bypass security software on a specific iPhone 5C. The FBI is trying to unlock this device—a phone provided by San Bernardino County to employee Syed Farook, the man who with his wife shot 36 people and killed 14—but it's obstructed by the phone's security feature, which might delete the contents of the phone after 10 failed attempts to guess the PIN passcode. For now, Apple is resisting this court order that asks the company to write code that would block the auto-delete feature and allow the FBI to "brute-force" the passcode.

Beyond the facts are various arguments about things like the limits of government power or the legal authority of law enforcement to gain access to evidence believed to be related to what has been labeled a terrorist act. Those questions will be resolved by the courts eventually. But both the FBI and Apple have tried to take the high ground in different ways within the court of public opinion—the FBI emphasizes the moral imperative of honoring the victims and fighting terrorism, while Apple proclaims an ethical duty it has to protect the privacy and security of millions of iPhone users worldwide.

Like many interested parties, Ars staffers have debated this aspect of the Apple court order many times over the past week without arriving at a consensus. Where staffers have come down on the topic has largely depended upon their views of whether we can take the government at its word—or whether we should share the fear expressed by Apple. Will this request actually create potential security and privacy risks with widespread consequences for millions worldwide? And if so, in what ways?

The feds’ moral appeal

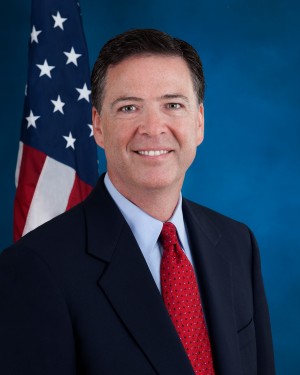

The moral element of the FBI's request was perhaps brought to light most prominently by FBI Director James Comey in a post to the blog Lawfare.

"We don't want to break anyone's encryption or set a master key loose on the land," he wrote. "I hope thoughtful people will take the time to understand that. Maybe the phone holds the clue to finding more terrorists. Maybe it doesn’t. But we can't look the survivors in the eye, or ourselves in the mirror, if we don't follow this lead."

Invoking the horror of Farook's terrorist act, Comey said he hoped that "folks will remember… why the FBI simply must do all we can under the law to investigate that. And in that sober spirit, I also hope all Americans will participate in the long conversation we must have about how to both embrace the technology we love and get the safety we need."

Some Ars staffers believe that Comey is on firm legal and moral ground—and that's all that matters. As one put it:

Search warrants are already the established mechanism for balancing privacy and the investigative needs of the government, and there is precedent for compelling third parties to assist. There’s no credible claim that this directly jeopardizes other phones. You’re worried about misuse? Sure, it’s a risk, but this particular instance ain’t misuse.

Certainly, that's how the larger government and law enforcement community see it. At the recent Suits & Spooks forum (an event held under the Chatham House rule), a panel of lawyers talked about the government's view of this problem. "You will never prevent law enforcement from getting into your house," one attorney framed it. "So people [in government] say, 'Why should it be different in cyberspace?'"

Another legal expert noted that it's unprecedented in history for people to be able to hide things completely from the government just by "scattering a little digital pixie dust on them." And while document shredders have been around much longer than encryption, shredding permanently denies both the owner and government access to the information it destroys. Encryption, on the other hand, is like magically reversible shredding.

But as Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia once put it, "There is nothing new in the realization that the Constitution sometimes insulates the criminality of a few in order to protect the privacy of us all.” And many of the lawyers participating in that Suits & Spooks forum were in agreement—there's little the government could do within the bounds of law to force companies to hand over a backdoor.

A recent report from the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University cast doubt on whether law enforcement actually needs special access to encrypted communications and data to gather evidence. In their summary, the report signatories wrote, "Are we really headed to a future in which our ability to effectively surveil criminals and bad actors is impossible? We think not. The question we explore is the significance of this lack of access to communications for legitimate government interests. We argue that communications in the future will neither be eclipsed into darkness nor illuminated without shadow."

That position was echoed in a conversation I recently had with Rebecca Herold, a faculty member at the Institute for Applied Network Security. She said that the solution to law enforcement's problems could likely be solved simply by using the metadata that already exists and can be collected or by software and Internet providers adding additional metadata that doesn't break the privacy of the conversation contained within encrypted messages. Herold likened what the FBI might find in the iPhone to Geraldo Rivera's "Al Capone's Vault" fiasco—they're likely to find nothing there because it was the only device Farook didn't destroy. He likely knew his employer had access to the device's contents.

reader comments

229