As info security expert Bruce Schneier and his Berkman Centre for Internet and Society colleagues pointed out in a report last week, there are now about 865 encryption-related products available globally. From free and paid VPNs to voice encryption tools, this market stretches far beyond the borders of the United States. Today, the encryption economy includes no fewer than 55 different countries across Europe, Latin America, the Asia-Pacific, and the Caribbean.

The sprawling ecology of software development creates an obvious problem for governments and security agencies seeking to monitor or contain privacy software. Free software and other distributed projects typically exist “on multiple servers, in multiple countries, simultaneously,” and companies selling anonymization software can relocate across borders with relative ease.

To those paying attention, none of this is news. Many observers also agree that legislative regulation of encryption would be a risky venture. But as a general rule, perhaps we shouldn't be too quick to assume that the Internet will always and inevitably find a way around the lumbering nation-state.

In the context of the current discussion, it’s worth bearing in mind that governments have many other options at their disposal when it comes to controlling the use of privacy software. While these options are rarely fully effective as a containment measure, they can have some effect when it comes to deterring new users from taking up particular technologies.

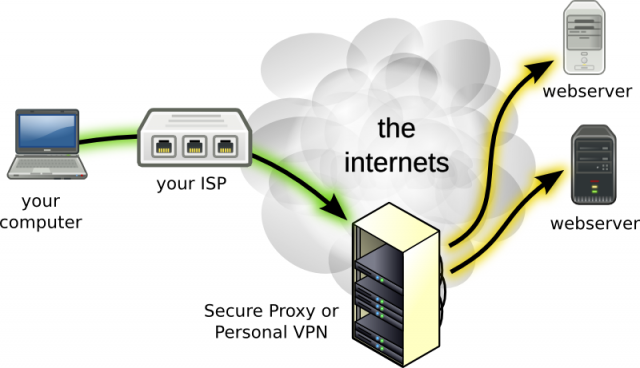

Let’s take the case of VPNs as an example. Once a business networking tool, the VPN has in recent years morphed into a subscription-based personal service for online security, anonymity, and remote server access, becoming one of the most user-friendly faces of privacy software. Governments around the world are now scrambling to keep up with the rapid take-up of VPN services and their diverse applications for consumers, citizens, and criminals alike.

As part of an international research project, a team of digital media researchers and I have been tracking and comparing international trends in VPN use, culture, and regulation. Over the last year, we have been studying how VPNs (and other privacy software) are being used for entertainment, politics, and communication in different countries. The results have been eye-opening.

One of the emerging themes is that different governments take different approaches to regulating VPNs. In countries with strong Internet censorship, a common strategy is a combination of legislative bans and network-level blocks. In China, home to the world’s most sophisticated Internet censorship system, numerous VPN websites have been taken offline under the guise of a crackdown on unlicensed telecoms services. VPN traffic has been disrupted via deep-packet inspection and port blocking, too. Similar ban-and-block systems are in place in several Gulf states, including Bahrain, Oman, and Saudi Arabia, and in Pakistan. Reports suggest that Russia has been considering such a move.

Elsewhere, technical blocks are being combined with more malicious measures. Freedom House reports that Syrian authorities “have developed fake Skype encryption tools and a fake VPN application, both containing harmful Trojans.”

And a new twist on the tale was recently seen in Iran, where the state has tried entering the VPN marketplace itself. According to advocacy group Small Media, Iranian authorities experimented in 2013 with setting up their own “official” VPNs. These VPNs were known to be government-linked but worked perfectly well for checking Facebook or YouTube, so long as users were not put off by government surveillance.

Then of course we have the whole issue of private regulation in the form of platform-level VPN blocking. Video services such as Netflix, Hulu, and BBC iPlayer—with variable levels of efficacy and enthusiasm—have all been using third-party commercial software to block access from IP addresses suspected of being used by VPNs.

What does all this mean for the future of privacy software products like VPNs?

The signs are mixed. Tech liberationists are probably right to insist that the distributed nature of cryptography and encryption mean that tech communities will usually find a way around top-down regulation. And service-providers have many options in the ongoing game of whack-a-mole, such as switching jurisdictions, changing server ranges, and inventing new workarounds.

At the same time, we should be careful not to assume that VPNs, voice scramblers, e-mail encryption, or any other technology products are entirely beyond the bounds of regulation at the point of use as well as production. Security agencies are far from powerless in this game, especially when the main aim is to discourage uptake across the board rather than stamp out use among techies.

In other words, the nation-state still has a few tricks up its sleeve. The stakes of this debate will only increase in the coming years as anonymization and privacy technologies enter further into the mainstream of tech culture.

reader comments

26