Microsoft is beefing up Windows Defender, the anti-malware program that ships with Windows 10, to give it the power to tell companies that they've been hacked after the fact.

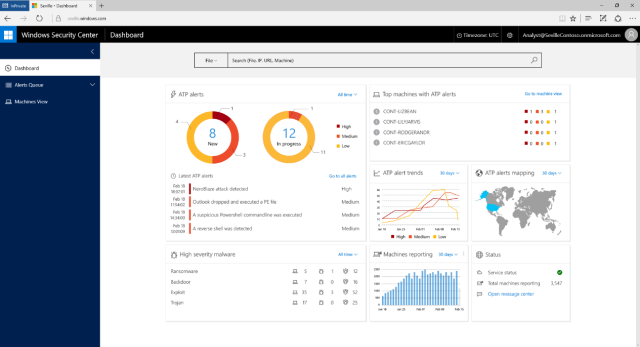

Attacks that depend on social engineering rather than software flaws, as well as those taking advantage of unpatched zero-day vulnerabilities, can evade traditional anti-malware software. Microsoft says that there were thousands of such attacks in 2015 and that on average they took 200 days to detect and a further 80 days to contain, giving attackers ample time to steal data and incurring average costs of $12 million per incident. The catchily named Windows Defender Advanced Threat Protection is designed to detect this kind of attack, not by looking for specific pieces of malware, but rather by detecting system activity that looks out of the ordinary.

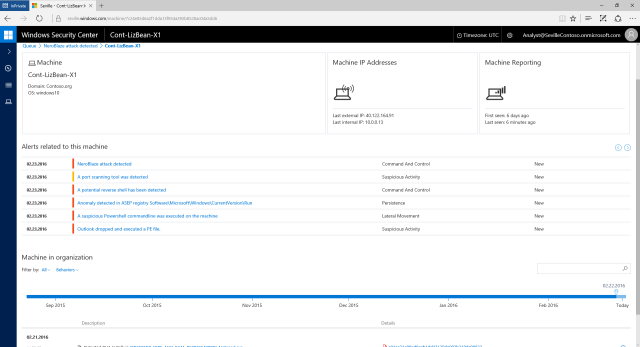

For example, a social engineering attack might encourage a victim to run a program that was attached to an e-mail or execute a suspicious-looking PowerShell command. The Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) software that's typically used in such attacks may scan ports, connect to network shares to look for data to steal, or connect to remote systems to seek new instructions and exfiltrate data. Windows Defender Advanced Threat Protection can monitor this behavior and see how it deviates from normal, expected system behavior. The baseline is the aggregate behavior collected anonymously from more than 1 billion Windows systems. If systems on your network start doing something that the "average Windows machine" doesn't, WDATP will alert you.

The system also strives to understand malicious behavior, too. More than 1 million suspicious files are automatically executed and examined within sandboxed environments in the cloud to build a better picture of the abnormal activities that malware and hacks can cause. All this data is crunched and analyzed using machine learning techniques to build models of normal and abnormal system activity. This means that not only can unusual PC behavior be identified, it can also be cross referenced against particular malware.

When errant system behavior is found, WDATP alerts administrators and gives them a view not just of a machine's current activities, but also historic information about network usage, files accessed, and processes run. That an intrusion has occurred may not be detected immediately, but this information should make it easier to determine when machines were compromised and just how far into an organization's systems the intruder managed to penetrate.

As is increasingly the way with Microsoft's software, the whole thing is cloud-based with no need for any on-premises server. A client on each endpoint is needed, which would presumably be an extended version of the Windows Defender client.

While announced today, WDATP is currently being tested on about half a million systems in a private beta. WDATP will become more broadly available in a public preview later the year. Microsoft has yet to decide on what kind of pricing model it will have.

The company says that more than 22 million enterprise customers have already made the switch to Windows 10 and points at the Department of Defense's plans to upgrade 4 million systems as further evidence that Windows 10 is not merely ready for the enterprise but is also a marked improvement on Windows 7 and 8.1. Part of the push for Windows 10 is its improved security features; Windows 10 includes a number of sensible new security features that Microsoft is trying to sell enterprise users on, such as Credential Guard (to make credential theft and lateral access within breached networks harder) and Device Guard (to more robustly lock malware out of systems).

WDATP is going to be part of that same push to Windows 10, and it won't be available for older operating systems. This arguably marks a broader shift in Microsoft's approach to enterprise software; traditionally, Redmond would, just like every other software vendor, support its software on multiple versions of Windows. In so doing, Microsoft acted as an enabler, allowing corporations to keep old versions of Windows long past their prime. Keen to avoid Windows 7 becoming "the new Windows XP," the company is being rather more aggressive in applying pressure on users to upgrade to Windows 10 sooner rather than later.

reader comments

84