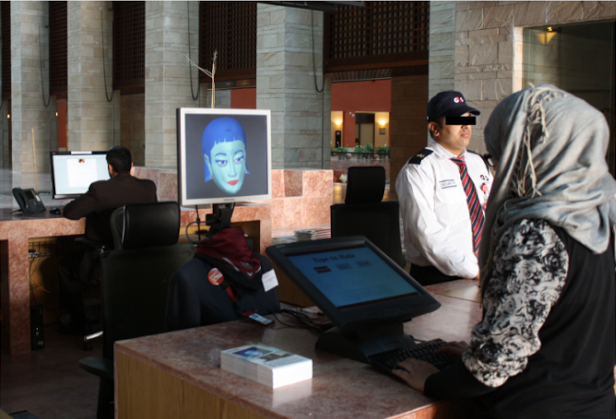

In 2010, a group of students and faculty members at Carnegie Mellon University in Doha, Qatar, introduced their campus to Hala, the latest in a line of what the school termed “roboceptionists.” Consisting of a truncated torso and an LCD screen featuring a blue-skinned female CGI head, Hala was designed to provide students and visitors with instructions, directions, and anecdotes in either formal Arabic or American English.

In addition to educating visitors about Qatar, Hala’s purpose was to explore human-robot interaction (HRI) in a multicultural setting. The population of Doha is a demographic mosaic; the city is primarily inhabited by expatriates from all over the world (most of whom speak Arabic and/or English). Because of this relative diversity, Hala interacted with visitors from a slew of countries, using features like natural language understanding and facial expressions to conduct, in Carnegie Mellon's words, “culturally appropriate” exchanges.

Among the school’s robotics department, Hala’s development sparked a flame of inquiry. If a robot could read different linguistic and visual cues, could its communicative abilities improve? What might that mean for the future of HRI?

In 2013, a group of researchers at Carnegie Mellon’s Pittsburgh and Doha campuses explored these questions by publishing one of the first multicultural HRI studies. Their hypothesis: if humans can relate to a robot on the basis of culture, they’ll respond more positively to the bot and recall interactions more thoroughly and accurately.

“If you have a robot that’s interactive, there’s reason to expect that a person will want to bond with the robot subconsciously,” Maxim Makatchev, one of the study’s researchers, told Ars. “If a robot makes bonding easier, the interaction will potentially be more successful, and expressing social cues makes it easier to bond with the robot.”

A bit of background is in order. Plenty of bots have been built to resemble humans’ varying appearances and behaviors, but they’ve reflected only their creators’ cultures. Scientists at the United Arab Emirates University developed an Arabic-speaking humanoid robot based on Persian scientist Ibn Sina; the American-built BINA48, the robot inspired by biotech executive Martine Rothblatt’s wife Bina Aspen Rothblatt, and Japanese engineer Hiroshi Ishiguro’s geminoids—which stand, perhaps, as the poster children for anthropomorphic robots—are hyperrealistic likenesses of their (mostly Japanese) inspirations.

“If you look at the human-like robots, for example, in Japan or in Europe, [their engineers] make them look like the people around them,” said Makatchev. “The Japanese robots are usually Asian, and the European robots are usually Caucasian, presumably because that's what the researchers look like.”

Since there’s little precedent for multicultural HRI, a colossal problem looms for any scientist who aims to broach the subject: stereotypes. Outfitting a nonhuman entity with an ethnic identity can easily fall prey to prejudice and reductivism, particularly if developers are exploring interactions with cultures with which they aren’t intimately familiar.

With this in mind, the researchers decided to test ethnic attribution using verbal and nonverbal cues that could be measured objectively: greetings, gaze patterns, politeness, response to mistakes, and response to disagreement. They divided four anthropomorphic robots that were based on Hala’s software architectures into two linguistic categories: native speakers of Arabic who spoke English as a second language (abbreviated as Ar) and native speakers of American English (AmE). To gain insight into these behavioral cues, the researchers monitored conversations between speakers of both languages and used crowdsourced surveys to gauge mannerisms for native speakers of each language.

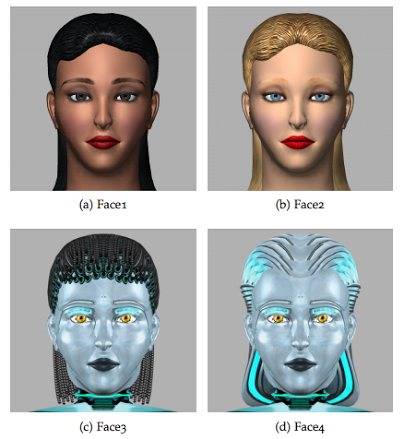

Each robot in the study had one of four unique female faces. (When asked why they were female, Makatchev said the Hala prototype offered a stronger foundation for designing a female robot than a male one.) Face 1 (dark hair, olive skin) was designed to portray a native Arabic speaker and Face 2 (blonde hair, fair skin) a white, American-born English speaker. Faces 3 and 4, which appeared more overtly mechanical, were used as controls to test the efficacy of the behavioral cues without the signal of appearance.

Thirty human Ar and AmE speakers held conversations with each of the four robots (whose responses were selected by a human operator) in which the humans typed requests for directions to various destinations. In each interaction, both parties spoke English, and researchers randomly and equally assigned behavioral cues to the bots. Those with Ar behavioral cues, for instance, greeted users with “Yes, ma’am/sir,” had a moving gaze, and used excuses to explain mistakes), while those with AmE cues said, “Hi,” kept their eyes on the user, and made a “lower lip pull”—an expression one might make while saying, “Eesh!”—in response to mistakes.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the study provided virtually no support for the cultural-bonding hypothesis. Few combinations of behaviors and faces showed differences in perception between the AmE and Ar participant populations; both groups viewed AmE bots as more animated, and both rated Face 4—the least humanoid—most likeable. Similarly, AmE humans didn’t view greetings like “Yes, ma’am/sir” as AmE behavior but found them likeable.

What’s more, communicative efficacy didn’t prove ethnically sensitive. When asked to recall robots’ answers to their questions from particular conversations, Ar and AmE participants showed no significant difference in recollection when discussing responses from either robotic group.

To parse the value of this conclusion, it's imperative to consider the study's limitations. The robots’ human likeness was minimal, and each had the same voice. Users typed their questions and responses, compromising their abilities to look forward and examine the robots' behaviors. Additionally, the study accounted for only two ethnic identities and used a relatively small sample size. How much, then, might results shift if these factors are changed?

Too little subsequent work exists to answer that question, but the Carnegie Mellon study may provide a foundation on which to explore robots’ roles in multicultural coexistence. If the conclusions of this study bear any validity, is it possible that prejudices humans harbor against one another don’t translate to their interactions with non-human entities, even when those things resemble humans? Can interactions with robots enlighten people about cultures they don’t know and thus the interactions they have with other humans?

Makatchev believes there’s potential. “Robots that express certain ethnicities can help bridge the knowledge gap between humans in certain ethnicities,” he said. “In Qatar, the local Qataris never have an equal power relationship with, for example, Southeast Asians. Most Southeast Asians come there as service workers or construction workers. There are no conditions for positive contact between Southeast Asians and Qataris. Maybe a technology like robots could facilitate positive contact by presenting themselves as an avatar of a certain ethnicity [in a context] which does not have this power imbalance.”

It's possible, but considering the current state of HRI, the interpretation seems rosy. Humanoid, idiosyncratic robots are relatively new, and humans might not take them seriously as cultural agents. Furthermore, in their current states, robots are time-consuming and expensive to build, and they’re inaccessible to most people. Given their distance from the human biological and social canon and the resources needed to create them, it's reasonable to doubt that they can realistically serve as cultural mediators—or that incorporating ethnic identities into robots can truly have any positive effect at all. (This rings especially true in the wake of Tay, Microsoft’s AI simulation of a millennial that, after a few hours of exchanges with 4Chan-caliber Twitter trolls, transformed into a vociferous champion of Hitler.)

Still, Makatchev said, “Whether we want it or not, some people will continue to [experiment with ethnic attribution in robots]. You can’t restrict these kinds of studies or these kinds of industrial designs. Even if there’s no academic research, it doesn’t mean that industry will not go that way.”

If ethnic attribution in robots is as inevitable as Makatchev says, there's reason to be concerned. Perhaps the largest issue is one of multicultural presence within the science and tech communities themselves. The diversity problem still looms large; though Carnegie Mellon’s experiments took advantage of ethnically varied settings, this isn't reflective of most environments in which technology is developed. It's potentially dangerous to create culturally representative technology in demographically homogeneous circles, where engineers might not enjoy the awareness provided by a broad multicultural scope.

If robots are, to an extent, reflections of their makers, it’s only when those engineers benefit from exposure to a wide range of perspectives, open communication, and heightened consciousness and empathy that any sort of constructive marriage of robots and ethnicity can happen. Only time will tell if it will.

Julianne Tveten is a journalist specializing in the sociopolitical currents of technology. At Ars, she's previously written about CSS colors, connectivity issues for American Indian populations, and open source voting.

Correction, 4/18: This article originally said, "Seventeen human Ar and AmE speakers held conversations with each of the four robots (whose responses were selected by a human operator).." regarding the cited study. The number of speakers was 30 and has been updated. Ars regrets the error.

Listing image by Maxim Makatchev

reader comments

45